As India celebrates its Independence Day this Tuesday, the annual holiday will come with an added layer of meaning: This marks 70 years since the achievement of its hard-fought nationhood.

British Crown rule in India dated all the way back to 1858, but by the 1940s — thanks largely to the work of Mohandas Gandhi — it was clear that, despite the many grand statements made to the contrary over the years, the system would not endure forever. Gandhi had become convinced that the U.K. would never willingly give India even partial self-rule, and began a civil-disobedience campaign to win independence through forceful passivity, though his peaceful efforts often inspired violence in others. “With each fast, each boycott, and each imprisonment (by a British Raj which feared to leave him free, feared even more that he would die on their hands and enrage all India), Gandhi came closer to his goal of a free India,” TIME reported in the lead-up to independence.

Finally, as Britain faced its own internal post-WWII problems and a changing of the guard in Parliament, Prime Minister Clement Attlee promised in early 1947 that the Raj would end by June of 1948.

The fateful date came sooner, on Aug. 15, 1947. On that day, by TIME’s count, a full one-fifth of all human beings alive suddenly became self-governing.

On the eve of independence, Jawaharlal Nehru, about to become the first Prime Minister of India, received a procession of Hindu holy men at his home in Delhi. Then, he and other political leaders gathered in the Constituent Assembly Hall. “Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge,” Nehru told those present. “At the stroke of midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.”

That stroke of the clock, TIME reported, was met with rejoicing:

And as the twelfth chime of midnight died out, a conch shell, traditional herald of the dawn, sounded raucously through the chamber. Members of the Constituent Assembly rose. Together they pledged themselves “at this solemn moment . . . to the service of India and her people. . . .” Nehru and Prasad struggled through the thousands of rejoicing Indians who had gathered outside to the Viceroy’s House (now called the Governor General’s House) where Viscount Mountbatten, who that day learned he would become an earl, awaited them. There, 32 minutes after Mountbatten had ceased to be a Viceroy,* Nehru and Prasad rather timidly, almost bashfully, told Mountbatten that India’s Constituent Assembly had assumed power and would like him to be Governor General.

Delhi’s thousands rejoiced. The town was gay, with orange, white and green. Bullocks’ horns and horses’ legs were painted in the new national colors, and silk merchants sold tri-colored saris. Triumphant light blazed everywhere. Even in the humble Bhangi (Untouchable) quarters, candles and oil’ lamps flickered brightly in houses that had never before seen artificial light. The government wanted no one to be unhappy on India’s Independence Day. Political prisoners, including Communists, were freed. All death sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. The Government, closing all slaughterhouses, ordered that no animals be killed.

The people made it their day. After dawn half a million thronged the green expanse of the Grand Vista and parkways near the Government buildings of New Delhi. Wherever Lord and Lady Mountbatten went that day, their open carriage, drawn by six bay horses, was beset by happy, cheering Indians who swept aside police lines. A Briton received a popular ovation rarely given even to an Indian leader. “Mountbattenji ki jai [Victory to Mountbatten],” they roared, adding the affectionate and respectful suffix “ji” usually reserved for popular Indian leaders.

But Gandhi, the magazine noted, was conspicuously absent. As it became clear that the Raj was ending, questions of what it would mean to have an independent India had split those who pushed for independence. Among other divisions — over communism, conservatism and more — the most significant was over whether the Muslim population would end up with a country of its own.

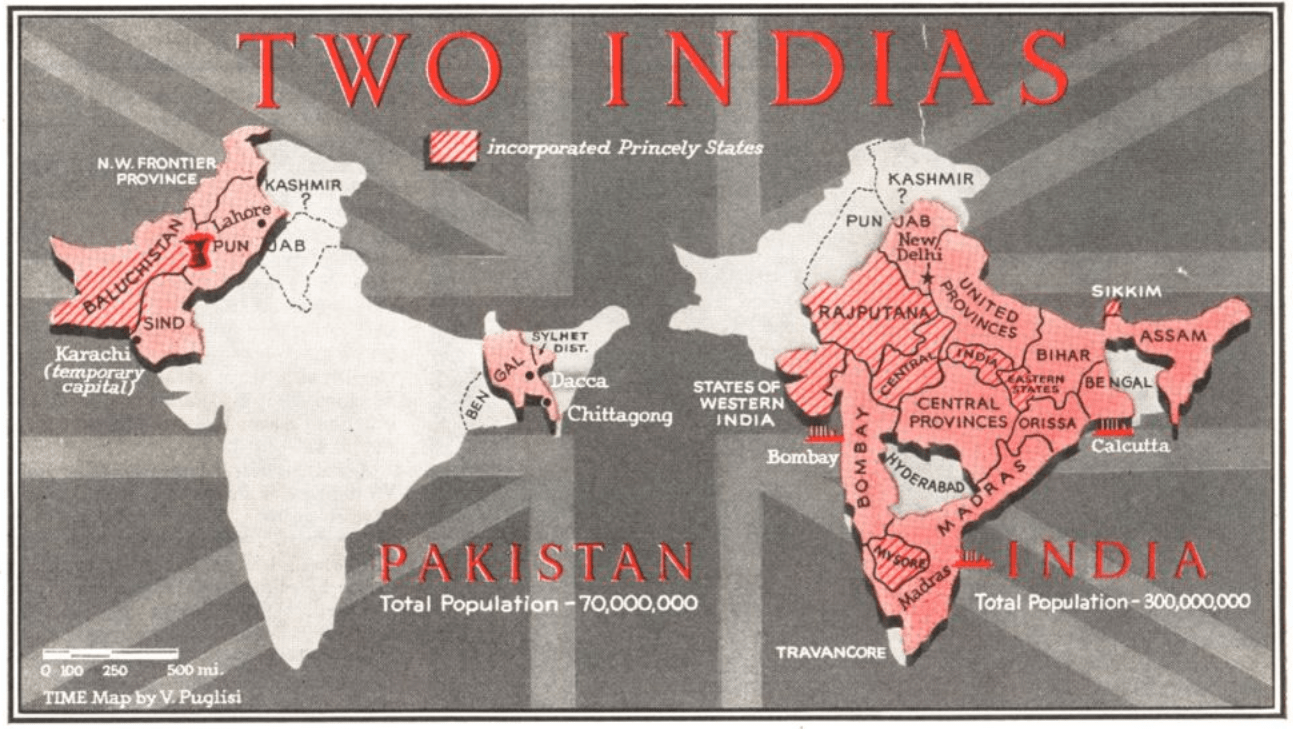

Under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, that nation would become Pakistan, though its borders remained uncertain even as the British departed.

As late as that June, Gandhi still held out hope — unsuccessfully — for a united India. Pakistan celebrated its Independence Day on Monday.

Read more: A New Way of Seeing Indian Independence and the Brutal ‘Great Migration’

Rather than attend festivities in Delhi, Gandhi remained in Kolkata, appealing to the people for peace between Muslim and Hindu neighbors. And, according to TIME, the appeal briefly worked. Though partition would be accompanied by violence and a massive (often involuntary) migration of citizens from one nation to the other, for one day there was peace:

“[On] Independence Day even Calcutta’s violence turned to rejoicing. Moslems and Hindus danced together in the streets, were admitted to each others’ mosques and temples. Moslems crowded round Gandhi’s car to shake his hand, and sprinkled him with rosewater. For the disillusioned father of Indian independence, there might be some consolation in the rare cry he heard from Moslem lips: ‘Mahatma Gandhi Zindabad‘ (Long Live Gandhi).”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com