They came for Mohandas Gandhi — the Mahatma, leader of the push for Indian independence from the British Raj — early in the morning.

Shortly before, his Indian National Congress party had met to decide whether to approve a plan to rebel, peacefully, against British rule in India, rejecting the U.K.’s proposed plan to give India dominion status — less than complete independence — after World War II came to an end.

When the party voted to approve the “Quit India” resolution, demanding immediate independence and launching a satyagraha civil-disobedience campaign in support of that goal, the British responded by going after Gandhi. As TIME reported, that arrest, though not Gandhi’s first, served as a spark to tip the passive resistance he favored into violent reaction:

A small boy in a tattered dhoti idly dawdled toe marks in the deep dust. Monsoon skies were slate-grey overhead. The oppressive heat gave added pungency to the smell of human filth in the Girgaun district of Bombay’s slums. Shopkeepers moved listlessly; talk dribbled in the bazaars. Suddenly everything changed. Word sputtered from mouth to mouth that the British Raj had jailed Mahatma Gandhi.

No longer listless, Hindus in the Girgaun ran riot. Four double-decker busses were wrecked. One was set afire, blazed high in the sky. Traffic snarled. Foreigners were stoned. So were police, who answered with tear gas, then fired directly into the crowds. The small boy ran from one trouble spot to another. Finally he remembered some blackjacks that he knew about. He got them, took up a stand on the street corner, sold them for one rupee each.

Thus last week did a tragic hour, damned by logic and twisted by emotionalism, come to the subcontinent of India. In a crisis caused by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s threat of open revolt, the British struck first. The slamming of jail doors on the leaders of the Indian National Congress party was their answer to Gandhi’s demand for immediate Indian independence.

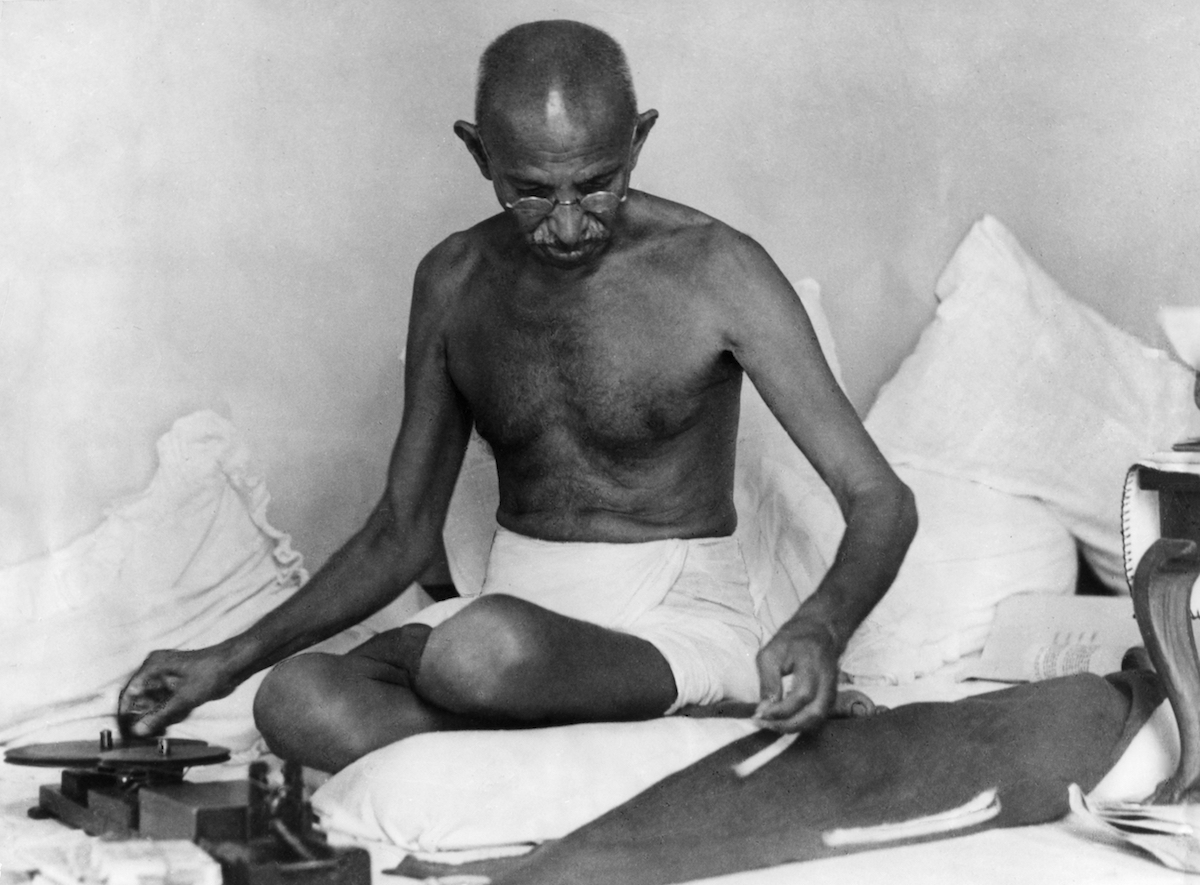

In the dawn’s early light, Bombay’s police commissioner arrested Gandhi at the home of Ghanshyam Dass Birla, a wealthy Indian industrialist. The elderly Pied Piper, who had been up until 2 a.m. writing reports and memoranda, was sleepy but good-humored. He was given an hour to get ready. During that time he had a breakfast of orange juice and goat’s milk. He heard a Sanskrit hymn and a few words from the Koran, read by a young Moslem girl. He scrawled a last-minute message to his followers. Then, with a copy of the Bhagavad-Gita (sacred Hindu poem), the Koran and an Urdu primer under his arm, a garland of flowers around his wizened neck, he was taken in the commissioner’s car to Victoria station. “Nice old fellow, that Gandhi,” the commissioner said. The train chuffed on to Poona. There the Mahatma was imprisoned in the rambling stone “bungalow” of the rich Aga Khan.

With Gandhi went Mme. Sarojini Naidu, poetess, and Madeline Slade, the British admiral’s daughter who has been Gandhi’s devoted follower for 17 years. Mme. Gandhi, older (73), tinier (barely four feet tall) and far frailer than her scrawny spouse who is still tough as nails despite the fiction that he is sickly, was allowed to remain in the Birla home. But that evening, she, too, was arrested when she tried to make a speech before 30,000 persons in a big Bombay park. The meeting was broken up, but not before other speakers read the last message from Gandhi: “Every man is free to go to the fullest length under ahimsa (non violence) for complete deadlock by strikes and all other possible means. Karenge ya Marenge! (Do or Die!)

As word of the arrest spread, so did the unrest. The British Raj responded by tightening its already strict control. Gandhi was accused — with the help of documents that had been seized from the Congress party headquarters — of supporting the Japanese in the war, while his supporters claimed that those documents had been “misinterpreted.”

Meanwhile, the rest of the world — particularly the U.S., at that moment an important ally of the U.K. but also naturally predisposed to support colonial rebellion against that ally — watched warily. (Gandhi was released in 1944, from what would be his last stint in prison. He died in 1948.) Decades later however, when Gandhi was included in TIME’s “Person of the Century” issue, the magazine noted that the world would eventually fully take the Mahatma’s side.

“It may be that this most Indian of leaders, revered as Bapuji, or Father of the Nation, means more now to the world at large,” the story noted. “Foreigners don’t have to wrestle with the confusion Indians feel today as they judge whether their nation has kept faith with his vision. For the rest of us, his image offers something much simpler — a shining set of ideals to emulate. Individual freedom. Political liberty. Social justice. Nonviolent protest. Passive resistance. Religious tolerance. His work and his spirit awakened the 20th century to ideas that serve as a moral beacon for all epochs.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com