After months of President Donald Trump alleging that he lost the popular vote in the 2016 presidential election because millions of people — including undocumented immigrants — voted illegally, his Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity will meet for the first time on Wednesday with the mission of investigating “improper voter registrations and improper voting, including fraudulent voter registrations and fraudulent voting.”

While there is no data to back up Trump’s claim, and in fact studies have found few documented cases of voter impersonation fraud in recent years, the president’s argument about immigrants is an old one.

In fact, it’s “eerily reminiscent” of voter-fraud claims made during the periods of heavy immigration to the U.S. more than a century ago, says Ron Hayduk, a political scientist at San Francisco State University.

In the early United States, the immigrant vote had not been such a concern. Though American fear of foreign enemies is as old as the nation, as demonstrated by examples like the anti-French Alien and Sedition Acts of the late 18th century, enthusiasm for the country’s brand-new democratic principles was given even greater weight in those early decades. Hayduk’s research found that at various points between 1776 and 1926, “40 states and federal territories permitted non-citizens to vote in local, state and even federal elections,” and that non-citizens were able to hold public office at various points. After all, in the mid-19th century, one just had to be a white, male property-owner to vote, and so-called “alien suffrage” (granting the right to vote to non-citizens) was seen as a way to lure foreign laborers — white, male ones — to help settle the frontier.

Before the Civil War, Southern states were initially resistant to alien suffrage, given that many immigrants were abolitionists; the 1861 Confederate Constitution mandated a prohibition on voting by persons of “foreign birth.” But the region eventually relented after slavery was abolished, as the South needed as much cheap labor as it could get.

In 1880s and 1890s, however, the state of immigration began to change.

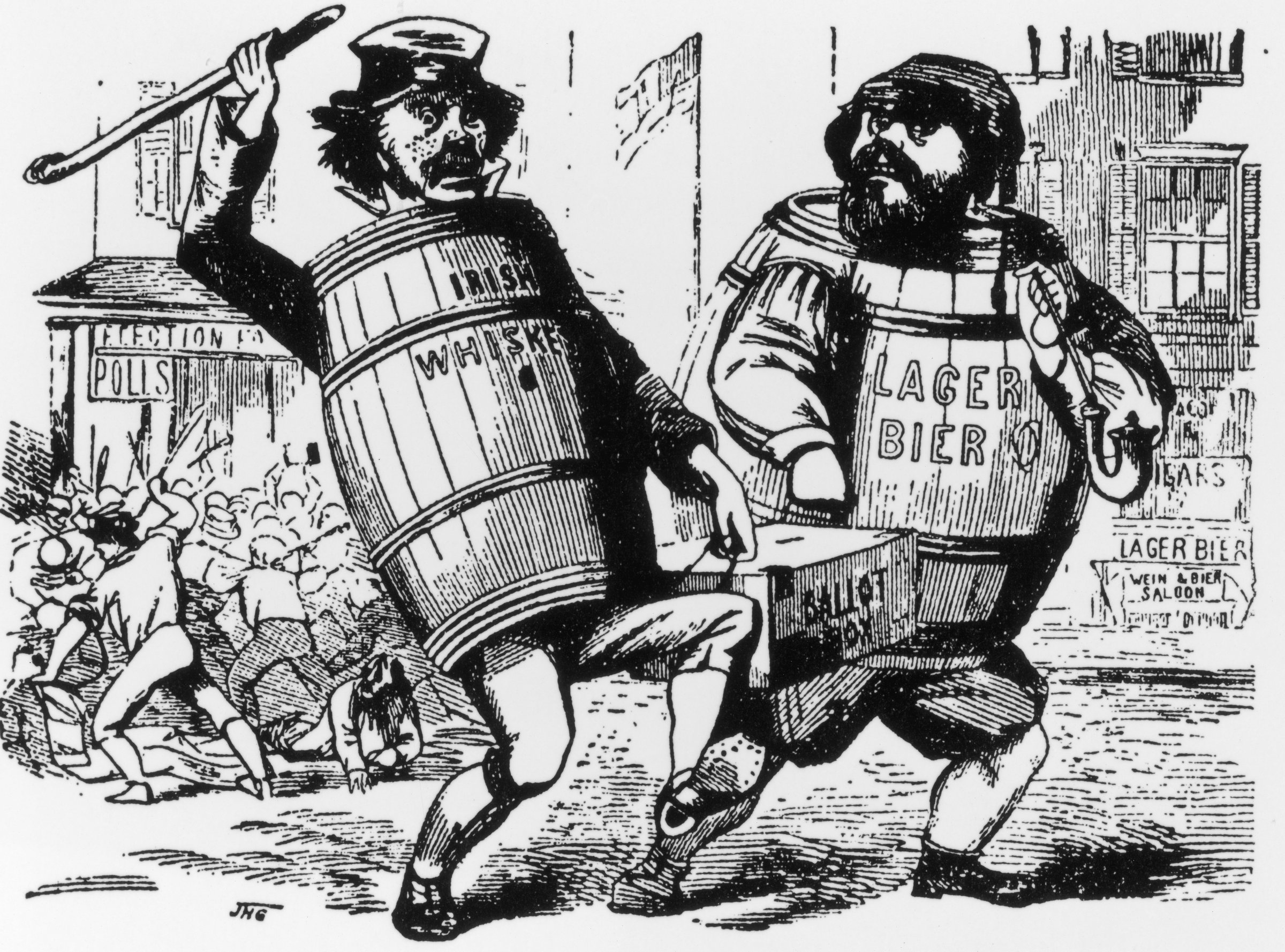

American cities experienced an influx of new immigrants in the period that followed: people from Southern and Eastern Europe who were not considered white enough at the time, people from Asia who were drawn across the Pacific by the Gold Rush, and people who were Jewish (a population that jumped from 80,000 in 1880 to 1.75 million in total by 1925 in New York City). And the numbers were huge: One U.S. Census report states that 23.5 million persons immigrated legally to the U.S. between 1880 and 1920. Many of these new residents became members of political machines like New York City’s Tammany Hall, which retained loyalty by providing services like job placement and clothing but were associated with corruption. “If you’ve ever heard the phrase ‘vote early and often,’ it’s a reference to multiple voting, and there are stories in the newspapers in the 19th century of partisans gathering a group of men, bringing them to a polling station, having them vote, buying them a whiskey, and then bringing them to another polling station,” says Margaret Groarke, associate professor of Government at Manhattan College and co-author of Keeping Down the Black Vote: Race and the Demobilization of the American Voter.

Because of the popular association between these new and different immigrants, who were already subject to discrimination, and organizations that were responsible for a lack of trust in the vote, many people changed their minds about whether alien suffrage was such a good idea.

A 1902 editorial in the Washington Post argued that a “marked and increasing deterioration in the quality of immigration” was leading to a need to keep those immigrants from voting (and to make it harder for them to become citizens). “Men who are no more fit to be trusted with the ballot than babies are to be furnished with friction matches for playthings are coming in by the hundred thousand,” the article asserted.

By 1900, only 11 states allowed non-citizen immigrants to vote, according to Hayduk.

And, as laws about alien suffrage changed, the narrative of the illegal immigrant vote emerged — as did steps meant to prevent that problem. It was not unusual for even immigrants who had already become citizens to be asked to unexpectedly show their naturalization papers, documents that many of them weren’t carrying around, before they could vote. (More infamously, similar methods, like literacy tests, were also used to disenfranchise black voters.) Some were told they could only register to vote at the county office. Most of those offices were only open during the day, effectively making it impossible for many poorer immigrants to do so, as a working-class day could easily be 12 hours long at that point. Some areas instituted residency requirements, requiring a voter to have resided in the same place for three to six months.

Measures designed to curb immigrant voting were one of several factors that marked the beginning of a decline in voter participation during the early 20th century, as the added difficulties of voting — both legally and illegally — kept voters away, as Hayduk explains in his book Democracy for All: Restoring Immigrant Voting Rights in the U.S.

Then, as now, Groarke says, there was “real debate about how much truth there was to the allegations of fraud” and whether the safeguards worked or did more harm. “We don’t have adequate evidence to understand what the extent of fraud then was,” she says, “and there was a realization by some people that those changes would lead to some legitimate voters not being able to vote.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com