Nowadays in November, one might see follicly capable men growing mustaches to show their support for men’s health causes, an annual event dubbed “Movember.” But in the mid-to-late 19th century, men had a different reason for growing out their mustaches in November: to show that they were old enough to vote.

These so-called “virgin voters” or “twenty-onesters” (so called for the voting age at the time, which was 21) would grow facial hair — or “facial foliage” as one Chicago newspaper put it in 1893 — to prove they were adults and not “beardless boys,” according to Jon Grinspan, Curator of Political History at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and author of the 2016 book The Virgin Vote: How Young Americans Made Democracy Social, Politics Personal, and Voting Popular in the Nineteenth Century.

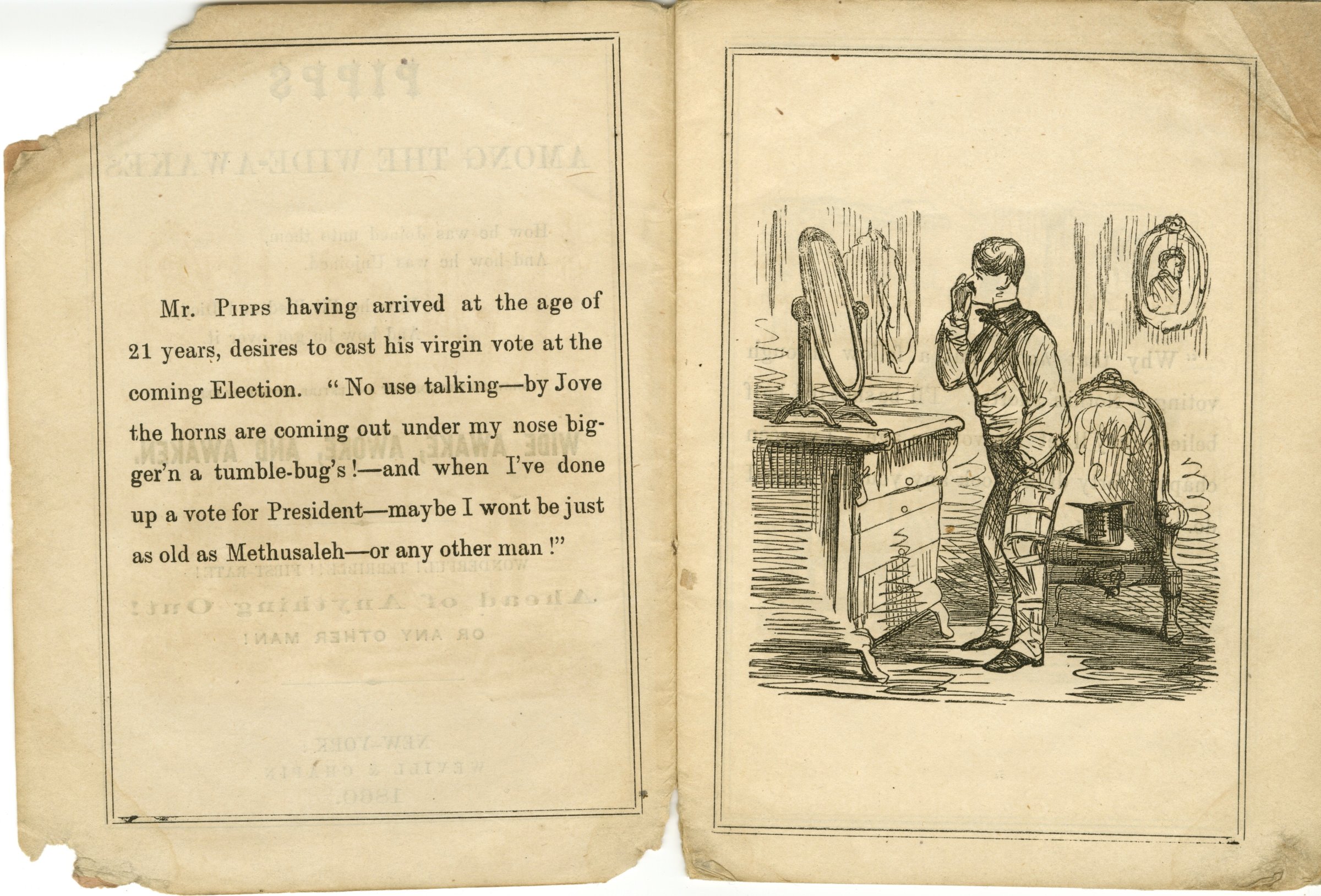

The twenty-onesters made themselves easy to spot in a crowd by dressing to the nines, and by spending the lead-up to the election growing the most impressive beard or mustache they could. Take, for instance, the above cartoon from Pipps among the Wide Awakes by folklorist Charles G. Leland, written in 1860 to persuade first-time voters to support Abraham Lincoln: “Mr. Pipps, having arrived at the age of 21, desires to cast his virgin vote at the coming Election. ‘No use talking—by Jove, the horns are coming out under my nose bigger’n a tumble-bug’s!'”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The Dec. 11, 1876, issue of the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel described the phenomenon of the “young man who deposited his maiden vote” after spending the whole morning primping so that he could cast his vote “with dignity and impressiveness.” And, at a time when it took so long to get to the polling place that Election Day was treated like a holiday, these “virgin voters” might also take advantage of the occasion to get drunk for the first time.

The significance of this hirsute ritual is two-fold, according to Grinspan. On the one hand, the visible signal that a young man would be able to vote made voting a “cultural touchstone” that all could see, something that was exciting and meaningful particularly at a time when voter motivation was generally high. (A record percentage of voters turned out in 1876.) On the other hand, he argues that the mustache could also serve as a reminder that “this is a world where not everyone gets to vote,” a signal of who was in and who was out. “By growing a mustache,” Grinspan says, “he’s saying to his sister or mother or African Americans, ‘I’m a citizen you’re not’ — separating people who were considered full citizens and people denied that right.”

The connection between political manliness and facial hair didn’t stop there either, as partisans might slam candidates considered young and inexperienced as men “with a scarce bit of down to shade their chin,” as one Philadelphia magazine wrote.

And the political benefits of a beard didn’t stop there: according to Lincoln lore, one of the most important pieces of campaign advice that Abraham Lincoln ever took—and from an 11-year-old girl—was to grow a beard.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com