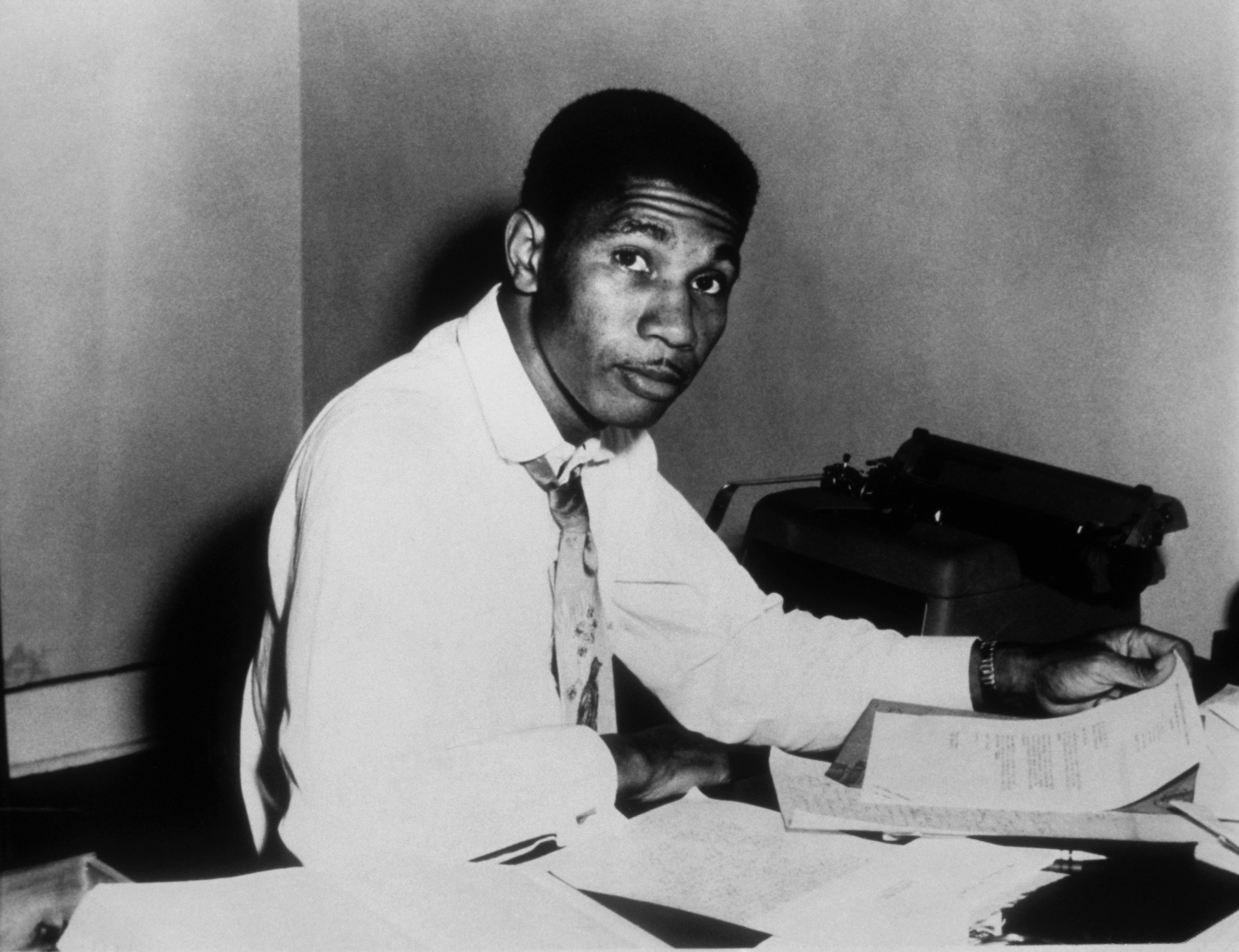

When Hillary Clinton delivers the commencement address at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn on Thursday, she’ll be stopping by a City University of New York school named in honor of a major civil-rights icon. But, though Medgar Evers had been an important NAACP activist in his lifetime, it was his 1963 murder at the hands of a white supremacist that brought his name to national newspaper headlines. In fact, the first time that Evers’ name appeared in the pages of TIME was in his obituary.

As the only full-time worker for the NAACP in Mississippi, Evers — who had served in World War II and graduated from the school that is now Mississippi’s Alcorn State University — had been accustomed to threats against his life and understood that he might go as a martyr. “I’m not afraid of dying,” he said at one point. “It might do some good.” After someone threw a gasoline-filled bottle into his carport, Evers said that if he died, it would be for a worthy cause cause: “I’ve been fighting for America just as much as the soldiers in Vietnam.”

Evers was shot in the back in the middle of the night on June 12, 1963, as he was about to enter his home in Jackson, Miss. He was 37, a father of three.

As people marched to demonstrate against the killing, police in Mississippi arrested and beat protestors. TIME’s 1963 obituary for Evers chronicled the violence following his funeral, which brought in about 4,000 people:

Among Mississippi Negroes, the anger over Evers’ murder coiled like a snake. Thirteen ministers began a silent walk, one by one, at widely spaced intervals toward city hall. To Jackson’s cops, this was just another protest march — and up came the paddy wagons to haul the marchers off. Next day, the cops rushed a group standing on a porch, clubbed some Negroes, grabbed a white man, throttled him with a billy club, kicked and beat him till blood gushed from his wounds. A day later, Negro youngsters again moved down the street in ones and twos, carrying tiny American flags (it was Flag Day). They, too, were blocked by police, relieved of their flags, and carried off to a hog-wire compound.

By Saturday morning, all was peaceful again in Jackson. The crowd that filled the Masonic Hall for Evers’ funeral service was well behaved. When it was over, the Negroes lined up to form a cortege behind the coffin, walked 20 blocks to a funeral home. It was one march that Jackson’s white city fathers had given the Negroes leave to make.

Then something snapped. Standing in front of the funeral home, a small group of Negroes began to sing. “Before I’ll be a slave,” they chanted, “I’ll be buried in my grave and go home to my Lord.” Other Negroes joined in. “No more killin’ here, no more killin’ over here.” Soon a whole chorus of swaying, hand-clapping people was sobbing, “No more Jim Crow over here, over here; I’m dead before I’d be a slave.”

Somebody began running. “Don’t run! Don’t run!” shouted a man. A woman cried “Freedom!” And then the mob was off, racing toward the downtown section of the city. They got as far as the first intersection. There, cops waited with dogs, tear-gas guns and rifles. As the mob spilled toward the police, the people yelled, “Shoot! Shoot! Shoot!” The cops rushed the crowd. One dog leaped for a woman. Screams tore through the air as the police grabbed the woman and carried her down the street.

Medgar Evers College was named in his honor in 1970.

Local police and the FBI quickly pinned the murder on a man named Byron De La Beckwith, whose fingerprints were on a gun that was found at the crime scene. A TIME report on Beckwith’s background found that he was obsessed with racism and frequently touted his family’s connection to the Confederacy. But two attempts to try him in 1964 culminated in hung juries.

His case was revived around 1990 after an investigative series ran in Jackson’s daily newspaper, the Clarion-Ledger. A hearing was rescheduled after Evers’ widow produced a transcript of Beckwith’s earlier trials, which had been thought lost. In 1994, Beckwith, 73, was found guilty.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Mahita Gajanan at mahita.gajanan@time.com