Think Washington is in an uproar and Trump is in trouble? For a true political maelstrom, cast your eyes south toward Brazil, where Chapter #843 in the seemingly never-ending “Car Wash” corruption probe looks set to bring down a Brazilian president for the second time in less than nine months.

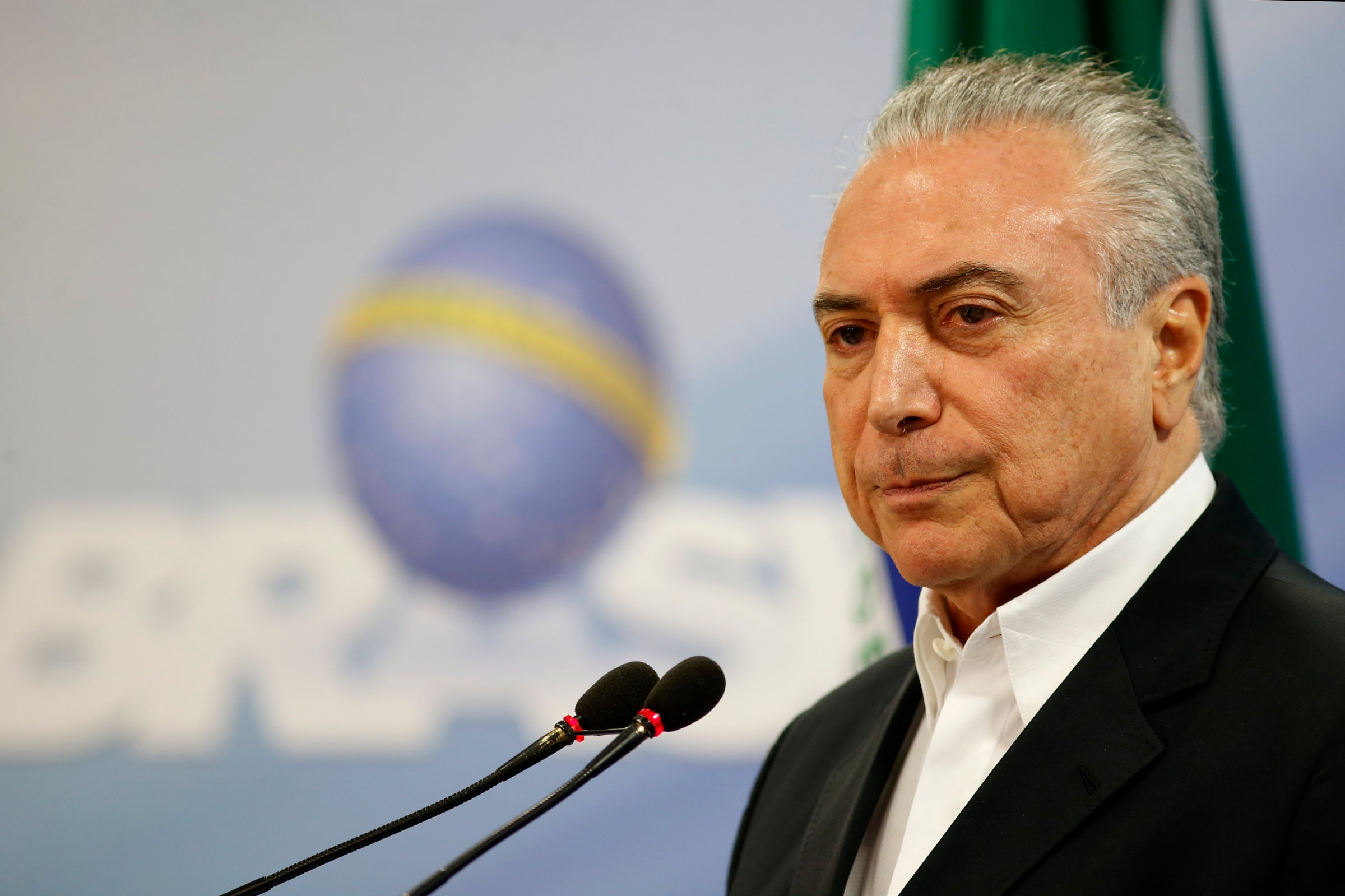

Michel Temer, who took office following the corruption-driven impeachment of Dilma Rousseff last August, stands accused of approving a bribe to buy the silence of imprisoned former House Speaker Eduardo Cunha. Temer insists that an audio recording offered as evidence was doctored and that he won’t resign. He will probably be forced from office, perhaps via a court ruling that Rousseff and Temer received illegal campaign contributions at the last election in 2014.

Brazil’s political scandal, known as Lava Jato, has reached an astonishing scale. The pain is widely spread; no fewer than 20 different political parties have had members implicated. More than 200 people have reportedly been charged with crimes. Two former Brazilian presidents, the heads of both houses of Brazil’s congress, more than 90 lawmakers and one third of Temer’s cabinet are implicated. The value of bribes paid as part of this scandal is estimated at about US$2 billion. Billion with a B.

Temer’s approval ratings have fallen to single digits. Several smaller parties have abandoned his coalition. In the courts and in the streets, his problems are growing. Even if he can survive a few more weeks, he will be the world’s lamest duck. His inability to advance a reform agenda that can kickstart Brazil’s economy, mired in deep recession for years, will probably cost him the allies he has left. If he goes, Congress will elect a new president to finish the Rousseff/Temer term, and the entire political class will face the wrath of voters next year. Just as U.S. and French voters pushed aside establishment figures in recent presidential elections, so Brazilians may move toward a true outsider as their next president.

Now for the good news. In a world where all major emerging markets are plagued with high levels of corruption, Brazil has proven that the country’s political elite are not above the law. That’s a crucial advantage for Brazil’s future. In many developing countries, governments use “anti-corruption” campaigns not to sweep away criminality but to strengthen their hold on power by targeting opponents and rewarding allies.

Today, Brazil faces political upheaval, and the uncertainty will continue through this year to the next presidential election in October 2018. Longer term, however, Brazilian judges and prosecutors have proven that no one is above the law. Over time, that will create a more politically and economically stable nation, one where citizens can begin to have more confidence in their government.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com