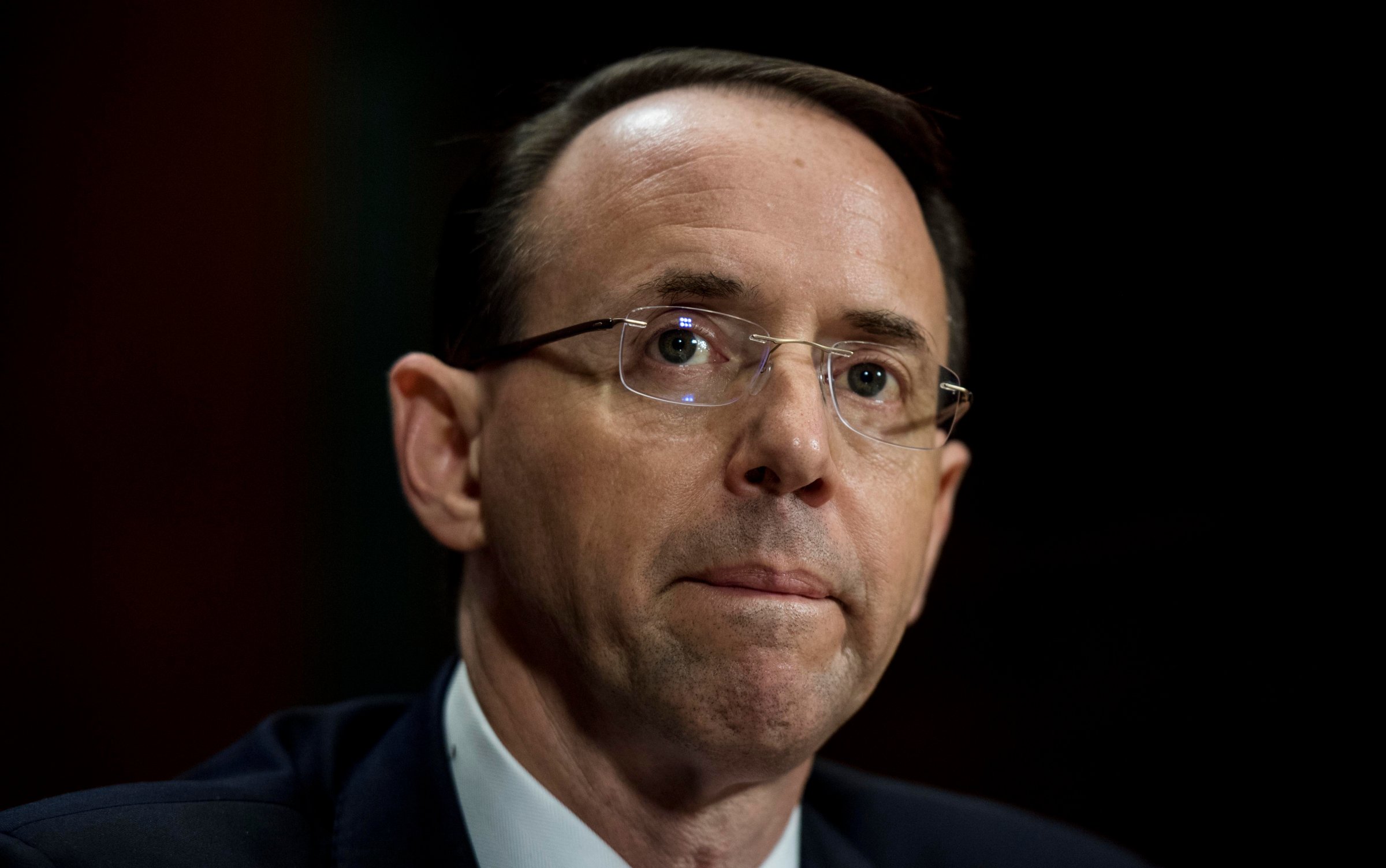

During his 27 years at the U.S. Justice Department, Rod Rosenstein has been known for his low-key presence, 1 a.m. emails and meticulous methods.

“When we had an important decision to make, he would go around a room and he would solicit people’s views, but at the end of it he was not afraid to make the call,” says Jonathan Biran, a lawyer who used to work with Rosenstein at the U.S. Attorney’s office in Maryland. “He’s not someone who would just make a rash judgment.”

Now his judgment is being tested like never before. Rosenstein is at the center of the swirling national controversy over President Donald Trump’s decision to fire FBI Director James Comey. The deputy attorney general wrote a memo that the White House initially claimed convinced Trump to axe Comey on May 9. And it is Rosenstein, 52, who has the power to decide whether to appoint a special prosecutor to probe the Trump Administration’s ties to Russia, an investigation some suspect was Trump’s real motive for firing Comey.

“It’s rare that any single person has to bear as much responsibility for safeguarding American democracy as you find yourself carrying now,” the New York Times editorial board wrote Thursday in an open letter to Rosenstein.

Top Democrats have also argued Rosenstein must appoint a special prosecutor to safeguard the integrity of the Russia investigation, which Comey was overseeing before he was sacked. “It is the only way to go,” Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer told reporters. Senate Democratic whip Dick Durbin said Rosenstein, who will meet with the Senate next week, should resign if he refuses. But Republicans oppose the idea. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said Wednesday that a new investigation “could only serve to impede the current work being done.”

Rosenstein’s role at the center of this political maelstrom is not a natural position for the career prosecutor. While he is registered Republican, Rosenstein has served nearly three decades at the Justice Department under five different administrations, earning a sterling reputation among members of both parties. In April he was confirmed to his position by the Senate in a 94-6 vote.

“He’s not going to be pushed one way or the other by simply public pressure or political pressure,” says Jan Paul Miller, a partner at Thompson Coburn LLP and former U.S. Attorney who has known Rosenstein since the late 1990s.

That independent reputation has been called into question in the wake of the Comey memo. Rosenstein’s three-page missive issued a careful but harsh assessment of the FBI boss’s conduct. “The way the Director handled the conclusion of the email investigation was wrong,” Rosenstein wrote, referring to Comey’s unusually public statements about an FBI investigation into former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s email practices. “As a result, the FBI is unlikely to regain public and congressional trust until it has a Director who understands the gravity of the mistakes and pledges never to repeat them.”

Democrats argued Rosenstein, witting or not, had become a political pawn. “The memo reads like political document,” Senator Dianne Feinstein of California said in a statement, “hastily assembled to justify a preordained outcome.”

Benjamin Wittes, editor-in-chief of Lawfare, published a post Friday calling on Rosenstein to resign. “The memo is a press release to justify an unsavory use of presidential power,” he wrote. “Rosenstein has been around the block in this town too many time not to know exactly what he was doing when he wrote this.”

Born in Philadelphia, Rosenstein graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in 1986, got his law degree from Harvard and clerked for a judge on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. He has worked on significant investigations for the Justice Department, including the independent counsel investigation of President Clinton and Hillary Clinton’s Whitewater investments.

In 1997, Rosenstein was hired as an Assistant U.S. Attorney in Maryland. He quickly earned a reputation as straight-laced and unpretentious, the sort who favors inviting friends over for takeout rather than going to ritzy restaurants. “He’s not a guy who is looking to work the cocktail party circuit or parlay this or any of his public service into any sort of fancy D.C. life,” says Megan Brown, a partner at Wiley Rein LLP who Rosenstein once hired as a summer intern. In 2005, Rosenstein was sworn in as U.S. Attorney for Maryland. He would go on to become the country’s longest-serving U.S. Attorney before being appointed by President Trump in January as Deputy Attorney General.

Democrats supported the appointment in part because Rosenstein is not known to be especially partisan. He “impartially pursues the cause of justice without regard to politics or any other influence,” five former prosecutors who worked with him in the Obama Justice Department wrote in a letter supporting his nomination. “That approach has earned him the trust and confidence of people across the political spectrum.”

Senator Ben Cardin (D-Md.), who has known Rosenstein since the latter’s years as U.S. Attorney in his state and supported his recent nomination, downplayed the importance of Rosenstein’s role in Comey’s firing in a statement to TIME. “I am convinced that the decision to fire the FBI Director was made by the President of the United States and not based on whatever memo Mr. Rosenstein was asked to write to justify the decision,” he said. “It’s unclear how much of the memo was his own work and how much pressure was exerted by the White House.”

But some associates worry Rosenstein doesn’t have the political instincts for his current assignment. “He basically let himself be used by President Trump and the Attorney General as a pretext for firing Comey,” says Michael Vatis, a partner at Steptoe & Johnson LLP who went to law school with Rosenstein. “I’m somewhat surprised that Rosenstein let himself be used in this way, because it seems like it was so obvious.”

“I don’t think he is motivated by politics, and I don’t think he engages particularly in political judgments and decision-making and hasn’t throughout his career,” adds a Washington-area lawyer who has known him for years. “It’s what made him a great prosecutor, but it also means he may not be astutely and acutely aware of political motivations that other people may have.”

Some news outlets have reported that Rosenstein was upset over the White House’s portrayal of his role in Comey’s ouster. The Justice Department denies the suggestion that the deputy attorney general threatened to quit. “Didn’t happen,” Justice spokeswoman Sarah Flores told TIME. In a brief interaction with a reporter this week, Rosenstein said he did not threaten to quit and had no plans to.

While Rosenstein may be new to the national political stage, longtime associates remain confident in his ability to grapple with the decisions ahead. “If there is anyone who has got the makeup to be cool under fire,” says Biran, his former colleague, “it’s Rod.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Tessa Berenson Rogers at tessa.Rogers@time.com