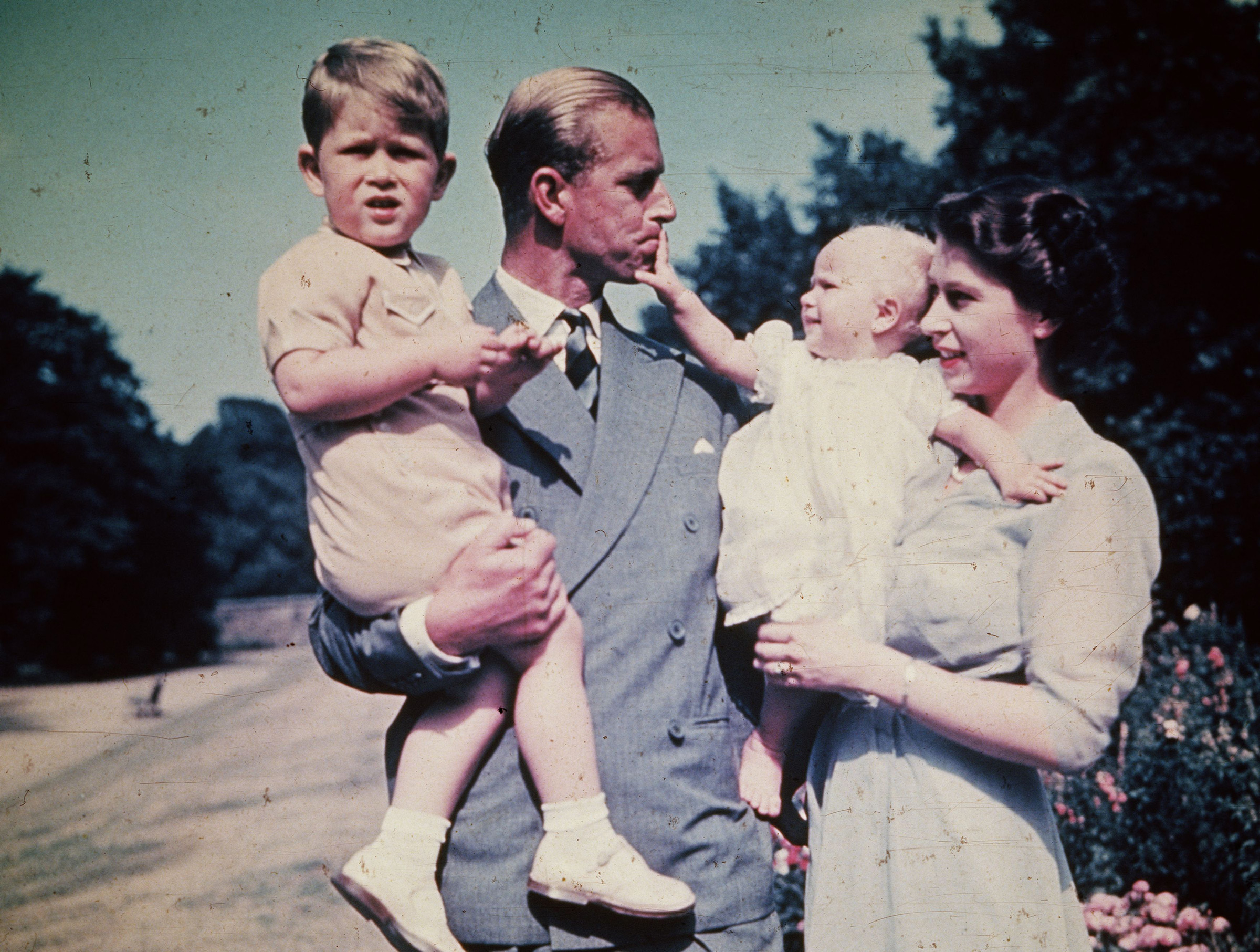

Until her father’s health began deteriorating, the couple could have been mistaken for any other happy young husband-and-wife. She had been just 13 when they met. He was the striking, handsome 18-year-old guide who took her and her sister on a tour of his naval college. She was infatuated. During the war, when he was on a battleship in the Mediterranean, she kept his photograph on her dressing-table, even though her father, who stuttered a lot, didn’t quite approve. But he came courting anyway and eventually permission was given to marry. They had a spectacular wedding, enjoyed postings to naval assignments, including Malta. They had had two kids by the time they were traveling in Africa and got the news. Lilibet’s father, King George VI, had died. At age 25, she had succeeded to the British throne as Elizabeth II. Everything also changed for her husband, Philip.

A man who was in Kenya with the couple recalled the transformations that took place on Feb. 6, 1952. Speaking to the journalist Fiammetta Rocco of The Independent, he said of the succession: “She seemed almost to reach out for it. There were no tears. She was just there, back braced, her color a little heightened. Just waiting for her destiny.” Her husband, by contrast, sat almost crumpled behind the newspaper he was reading. “He didn’t want it at all. It was going to change his whole life: take away the emotional stability he’d finally found.”

Prince Philip died Friday morning at Windsor Castle, Buckingham Palace said. He was 99.

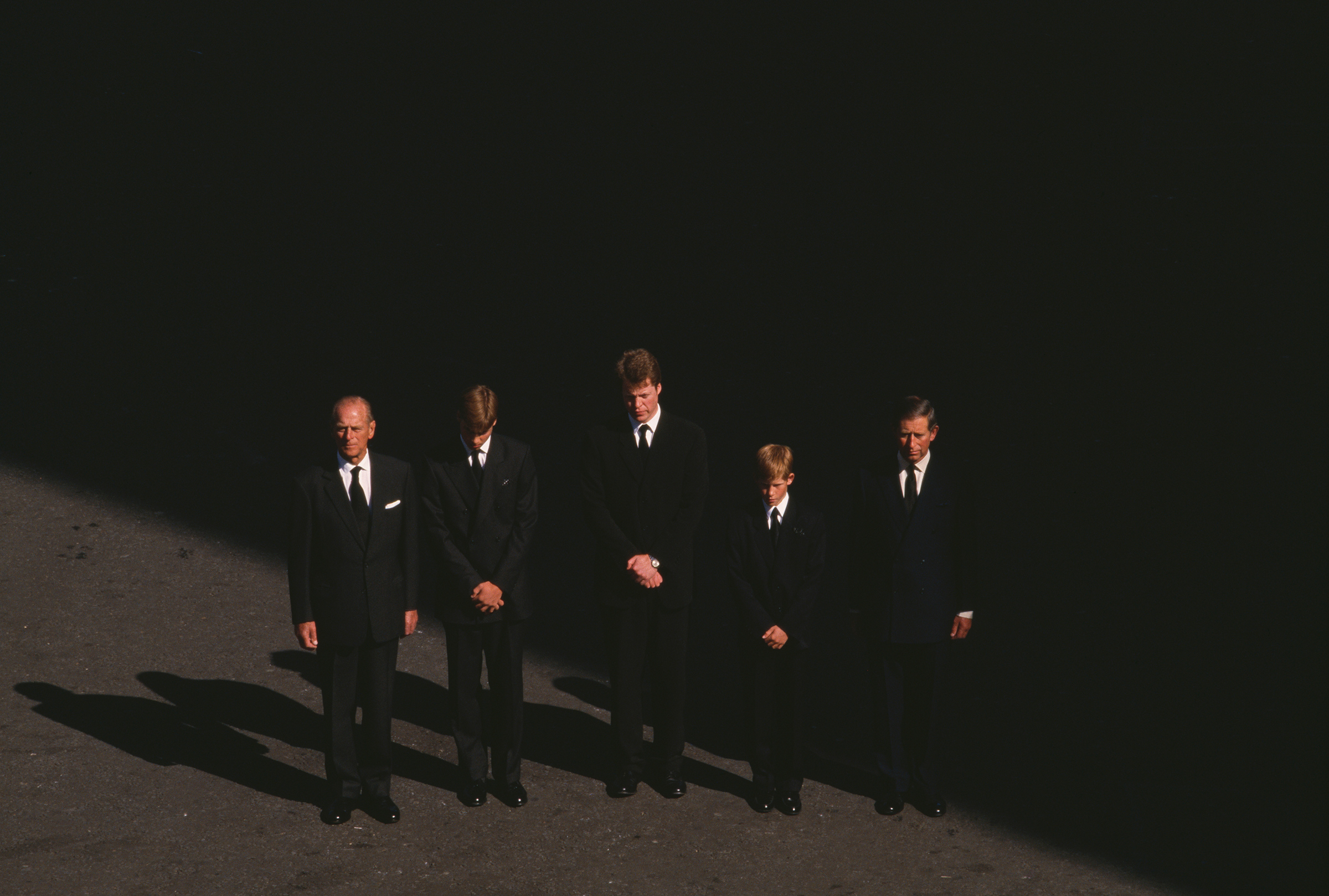

Philip’s health had been deteriorating for years, with each scare making headlines. In 2018, Prince Philip underwent a hip replacement—and just weeks later made a grand entrance with the Queen at the royal wedding of his grandson Prince Harry to American actress Meghan Markle. Later, Philip was examined by a doctor after he was in a car accident at Sandringham in January 2019 that flipped the Land Rover he was driving and injured two female passengers. He spent four night in a London hospital that December to treat a “pre-existing condition,” and was released just before Christmas. The retired Prince then kept a low profile during the coronavirus pandemic while the Queen primarily fulfilled her duties remotely. He was hospitalized again in February 2021 for what Buckingham Palace vaguely described as a “precautionary measure” after “feeling unwell.”

Philip had long ago surpassed the record for a man with the title of Consort. The closest was Philip and Elizabeth’s common great-great grandfather, Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, who was Prince Consort to Queen Victoria during their 21 years of marriage. Philip, who received the title of Duke of Edinburgh upon marrying Elizabeth in 1947, would, before retiring from public engagements in the summer of 2017, perform the duties for seven decades, through scandals and flamboyant in-laws, with just enough audible grousing from him now and then to make everyone remember what a strange business it was.

His Unstable Upbringing

If anyone was a princely pauper, it was Philip Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glucksburg, who was born in 1921 atop a kitchen table on the island of Corfu in the Ionian sea. His father was the seventh son of a Danish prince, who had been plucked out of Scandinavia to become King of Greece. The Greek royal house was constantly in and out of power depending on coup d’etats, until the monarchy was officially abolished in the 1970s. Philip was 18 months old when his father had to flee Greece and was never anywhere close to ever becoming King of the Hellenes. His mother was a Battenberg, a British family of German origin that changed its surname to Mountbatten during World War I, about the same time the British royal family opted to become the Windsors instead of the Saxe-Coburg-Gothas.

His father, Andrew, was addicted to gambling; his mother, Alice, was practically deaf and communicated via sign language. Their marriage ended when Philip was 10 years old. Raising her four daughters and young son by dint of loans, limited family legacies and hand-me-downs, Alice of Greece would eventually seek solace in religion and become a nun. (At the end of her life, she lived in Buckingham Palace, walking the halls in her wimple.) Her daughters would seek their fortunes in marriages in distant places. Philip was shuttled from country to country: from Greece, the family moved to Paris; when his parents split up, he ended up in England for a couple of years and then was taken over by German relatives. In 1992, when an interviewer asked him what language he spoke at home, he responded, “What do you mean by ‘at home’?”

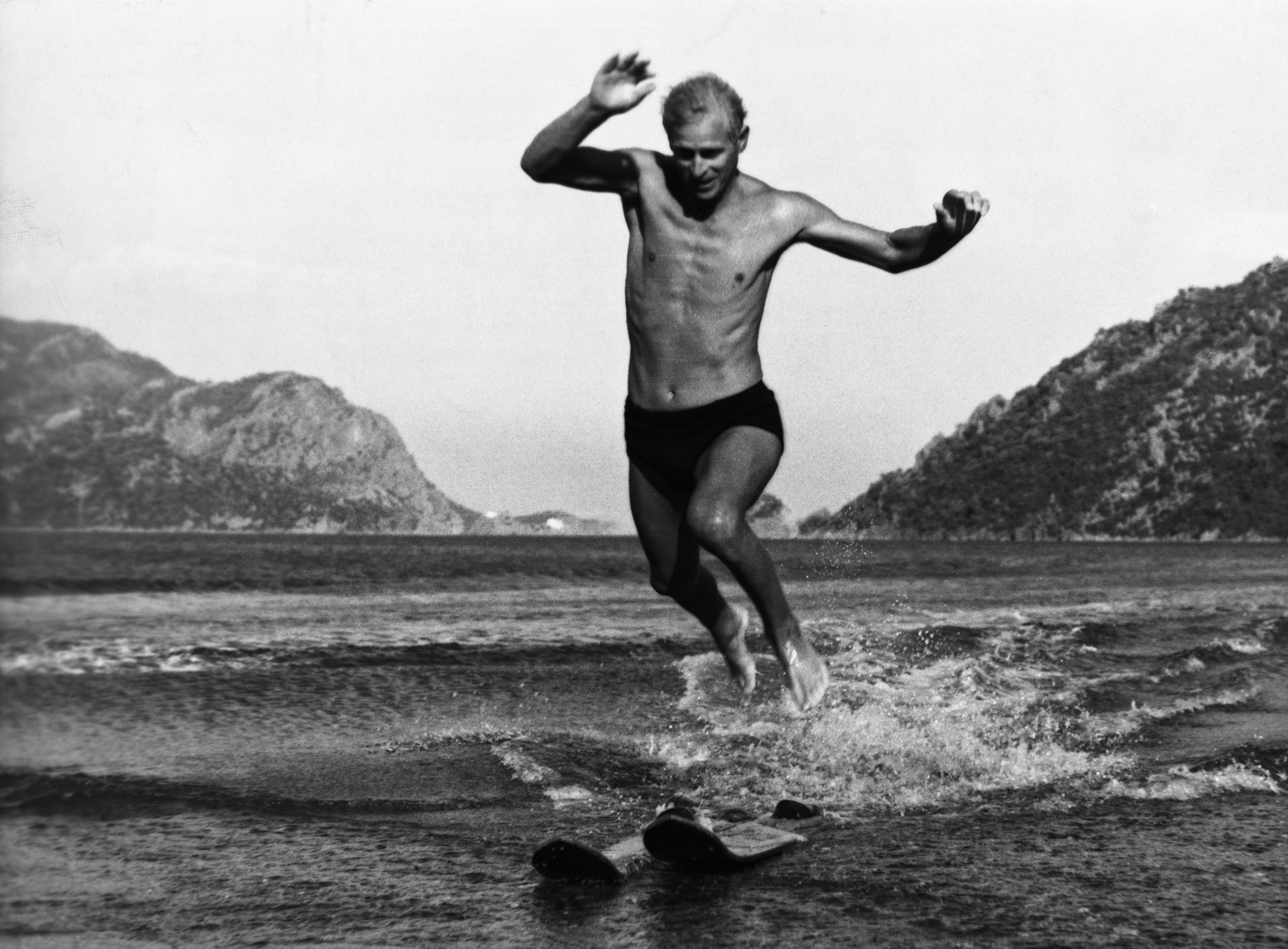

The unanchored life bred insecurity into the young Greek (or Danish, as you would have it) noble. He found a harbor in Gordonstoun, a school set up in Scotland by a German exile who had helped to run a school by one of Philip’s relatives on the continent. Gordonstoun’s combination of pacificism and physical discipline would help define him for the rest of his life. He would send his first child, Charles, there to be inculcated in its almost monastic philosophies—and the year-round cold showers and cult of derring-do, a kind of Shaolin Temple of the West. While its influence is clearly perceptible in the Prince of Wales, the heir to the throne has reportedly told confidantes that he hated his time at Gordonstoun. The alternative could have been Eton where Charles might have made important connections. Instead, Philip’s decision took his son away from a formative center of political and societal power and influence.

Yet Gordonstoun was central to Philip. His pursuit of what might have been a lifelong career in the Royal Navy was propelled by Gordonstoun’s tenets. But then he met Princess Elizabeth, the heiress presumptive to the throne. And while George VI may have looked askance at a Greek Orthodox royal from the wrong side of the track, his daughter could not be argued into considering any other potential match. Philip’s uncle, Lord Louis Mountbatten—the closest to a real father he had—would later claim credit for putting the future queen together with her consort. But the likelihood is that Lilibet’s passion for her distant cousin overcame any obstacles her father put in the way. The dynasty’s last crisis was over a matter of the heart: When George VI’s brother, Edward, abdicated in order to marry an American divorcee—an impermissible entanglement for the head of the Church of England. In Elizabeth’s case, the solution was simple: Philip gave up Greek Orthodoxy and was accepted into the Anglican communion. They were married on Nov. 20, 1947. She was 21; he was 26.

Adjusting to Royal Duties

Being Consort to the British Sovereign may have been more difficult than any feat demanded by Gordonstoun. Philip was always one step behind Elizabeth, always deferring to her in public. For a brief five years, he had been the official head of the family (indeed, her official title until her accession was Duchess of Edinburgh)—then everything was hers. Her Majesty’s this; Her Majesty’s that; Her Majesty’s mark here there and everywhere. Philip’s reported insistence on leaving his own mark may have led to a post-coronation rupture in their relationship. At one point, he proposed changing the name of the dynasty to include his name (at his marriage, he had, wisely, given up Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glucksburg for his mother’s surname, Mountbatten). He wanted his family to be called the Mountbatten-Windsors. His wife would not hear of it. Furious, Philip reportedly said, “I’m just a bloody amoeba! That’s all!” One palace insider interpreted the outburst to mean that the Consort felt he was just the equivalent of a sperm donor. It would be nearly eight years between Elizabeth’s accession in 1952 and the birth of the couple’s third child, Andrew, in 1960. Their fourth and youngest child, Edward, was born in 1964. The Duke would always be sensitive about his role. Asked by the BBC about it, he said: “Constitutionally, I don’t exist.”

The dysfunctional nature of his own upbringing did little for Philip’s own child-rearing skills. His disastrous relationship with his eldest child, Charles, was an open secret, remarked on by everyone. The son could never seem to satisfy the father. Even as a grown man, Charles was known to burst out in tears over remarks by Philip, who preferred his second son, Andrew. His favorite child, however, was the no-nonsense Princess Royal, Anne, his only daughter. Yet, Philip was only one-half of the family’s parental machine. The Queen herself was perceived as a distant if not cold mother.

His Complicated Bond with the Queen

Philip was always publicly loyal to his Queen, evidenced by his immense amount of appearances and charity work. But his faithfulness to his wife was another issue. Rumors dogged him throughout his public life. In her extraordinary 1992 profile, Fiammetta Rocco of The Independent brought up the subject. He brushed it aside with a laugh, saying “Have you ever stopped to think that for the last 40 years, I have never moved anywhere without a policeman accompanying me? So how the hell could I get away with anything like that?”

Philip and Elizabeth did exude a palpable affection when they were seen in public together; and in unguarded moments, the usually austere queen was, in the word of one observer, “kittenish” when interacting with her husband. While celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary in 1997, Elizabeth called him “my strength and stay all these years,” adding that, “I, and his whole family, and this and many other countries, owe him a debt greater than he would ever claim, or we shall ever know.” Yet, Elizabeth and Philip — while married — may have lived apart more often than otherwise. They occupied different bedrooms in Buckingham Palace and other royal residences. The only bed they shared was in Balmoral. He disliked her corgis. They did not regularly speak in the morning — it was their private secretaries who coordinated their schedules. If they dined together at Buck House, they parted ways after the meal — he to read, she to watch television.

To almost everyone she is The Queen (except for her children, to whom she is “mummy”). Even when Philip spoke of his wife to others, he would refer to her as The Queen. But when they spoke to each other, he still called her “Lilibet,” an ancient term of endearment, a relic from the brief early years of marriage before she ascended the throne and he became the ceremonial Royal Consort, the conjugal prop of the regnant queen. In his interview with Rocco, he offered an unfinished yet poignant sentence. “People forget what it was like when the Queen was 26 and I was 30, when she succeeded. Well that’s when things started…”

Or when they ended.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com