To ring in the year of the Rooster, which begins with Chinese New Year on Saturday, tradition holds that celebrants should feast on foods like dumplings, tangerines, fish, noodles and rice cakes because some of the Chinese words for these foods also sound like the words for fortune, good luck and abundance.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., those who celebrate by enjoying Chinese food will likely end their meals with another take on fortune: the fortune cookie.

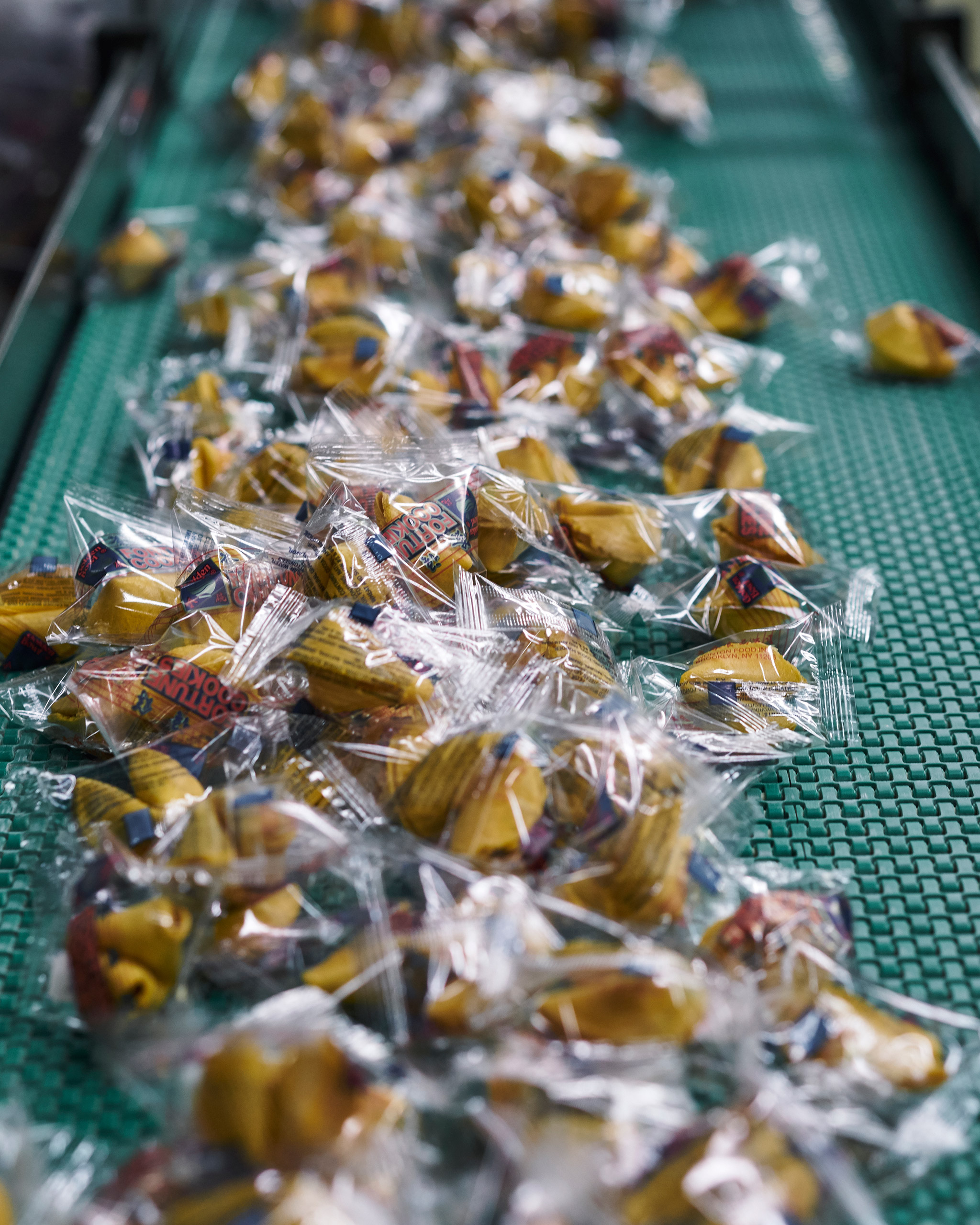

That sweet treat is the product of more than a century of complicated—and not always pleasant—history. And that history is now changing, as the Chief Fortune Writer at Wonton Food Inc., which identifies itself as America’s largest manufacturer of noodles, wrappers and fortune cookies, hands the reins to someone new. During this transition, Wonton Food gave TIME a look behind the scenes at its Queens, N.Y. factory, which churns out 4.5 million fortune cookies a day, to see fortune-cookie history in the making.

“I have writer’s block,” says Donald Lau, a former corporate banker who has for the last three decades been Chief Financial Officer and Chief Fortune Writer at Wonton Food. “I used to write 100 a year, but I’ve only written two or three a month over the past year.”

So for the past six months, he’s been training his successor: James Wong, 43, a nephew of the original founder of Wonton Food. Wong is now officially the Chief Fortune Writer.

“I passed the pen to him,” says Lau. “It’s his responsibility now.”

Crumby Origins

Wong and Lau are part of a long American tale that, ironically for a product that often bares uplifting messages, has a depressing backstory.

The fortune-cookie origins story that Lau chooses to believe is one that dates back to the Ming Dynasty, when people would give each other mooncakes containing secret messages. But research by Yasuko Nakamachi, a Japanese folklore specialist, has pinpointed the precursors of fortune cookies to small bakeries around a popular Shinto shrine outside of Kyoto, Japan, that had been making crackers in the shape of fortune cookies. The treat’s journey to the U.S.—and to being perceived as a Chinese dessert—starts in the late 19th century, during the California Gold Rush, when a different kind of fortune could be made.

American Protestant missionaries stationed in the south of China spread word of what was happening on the other side of the Pacific, and adventurous Chinese men were lured to America by the prospect of gold. By 1870, they represented almost 10% of the population in the state of California and about 20% of the state’s labor force, according to Yong Chen, a professor of history at the University of California, Irvine, and author of Chop Suey USA. Chinese immigrants began to work on farms as agriculture ramped up after the Civil War, and also worked building railroads. Despite their positions in critical jobs for the nation’s growth, many white Americans looked down on them. In 1882, Congress passed the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act, which basically banned Chinese manual labor, Chinese immigration and prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming U.S citizens.

Kept from lucrative jobs and banned from becoming legal residents if they were manual laborers, many of those who had come over before 1882 turned to the service sector, according to Anne Mendelson, author of Chow Chop Suey: Food and the Chinese American Journey. They started laundry businesses and restaurants.

Meanwhile, the racism and stereotyping that Chinese immigrants suffered also extended to Japanese people. But—perhaps because Japanese immigration was taking place at a slower pace—the initial 1882 law did not keep them from manual labor jobs. There was a racist perception that “the Chinese were really cunning and malevolent and would take any opportunity to take over this country,” Mendelson says. “And somehow, because the Japanese had not immigrated in as large numbers, people didn’t form the same idea of them as being filthy and malicious.”

As that population of Japanese Californians grew, they began to get into the service sector too. In the early 20th century, realizing that their native cuisine was too exotic for many American palates, they instead opened Chinese restaurants, which by that point had become familiar to Californian diners of all backgrounds. But, in doing so, they brought some of their own traditions to the Chinese-American table. Though it is not known exactly who invented the fortune cookie, the American version was a product of this amalgamation, says Jennifer 8. Lee, author of The Fortune Cookie Chronicles.

Things changed after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Feb. 1942 Executive Order 9066 authorized the military to designate certain regions as “military areas,” which enabled them to force the relocation of many Japanese-Americans to internment camps. Many of the Japanese-American people who owned the restaurants where fortune cookies were served were locked up. Lee says it was during this era that fortune cookies “mysteriously jumped from being basically something that was clearly defined as Japanese to something that is Chinese.”

At the same time, during World War II, the demand for fortune cookies increased as soldiers who were passing through California visited Chinese restaurants that served the treats, and brought that taste home with them to middle America. And so the fortune cookie spread across the U.S., becoming a symbol of the Chinese presence in America—a thriving presence these days, as people of Chinese descent are the most widely represented group of Asian-Americans, the fastest-growing racial group in the U.S., according to a Pew study.

And that tasty ending is appropriate, in a way: There is a type of Chinese fortunetelling, says Min Zhou, professor of Sociology and Asian-American Studies at the University of California Los Angeles, that holds that “there is always a way to turn your bad fortune into a good one.”

Catering to Different Tastes

But fortune cookies have remained a distinctly American phenomenon. In the early 1990s, Wonton Food Inc. attempted to expand its business in China, but found that the idea didn’t quite translate. Chinese diners, unfamiliar with the idea, kept accidentally eating the fortunes, Lau says. (Americans have sometimes gone the opposite way: a survey in the late ’80s found that nearly a quarter of diners don’t actually eat the cookie.)

“The company spent a lot of money to explain what a fortune cookie is,” says Lau. “It took too much time. And at that time, about 30 years ago, I think the government was not encouraging. If someone found a fortune, the government may have considered it superstitious.”

In general, the idea that modern Chinese history would have made the nation less receptive to something like fortune cookies makes sense, says Herb Tam, director of exhibitions at the Museum of Chinese in America, which is currently hosting an exhibit about Chinese food in America. Reform efforts by the Communist government in the 1950s and ’60s trickled down to how people ate and which ingredients were available. “People had problems just getting enough rice and basic staples to go around,” says Tam, “so by the time fortune cookies came around, I don’t think there was much of a place for such a weird, luxury item.”

Today, though the Chinese economy has changed significantly, fortune cookies are still not widely consumed there—and in fact, just as the economic and political history of the 19th and early 20th centuries helped create the fortune cookie, new global forces are at work. Thanks to globalization, it’s easier for American consumers to access real Chinese food and other goods, so the climate that produced something like the fortune cookie is disappearing.

Leaving a Sweet Impression

In Japan, the older the fortune, the more valuable it is, as Nakamachi has put it. Yet in the U.S., fortune-cookie fortune writers are pressured to come up with new, unique, inspirational messages all of the time.

And the fortunes they come up with today are the product of very recent history.

Lau says that when he became Chief Fortune Writer in the ’80s, the yellowed stack of fortunes presented to him sounded like vague horoscopes (“You will meet a new friend tomorrow”). Nowadays, they contain fewer predictions and more sayings that could help people be happier. He has also attempted to use U.S. politics as an inspiration for fortunes—”Watching the debates on TV during the primaries last year, when everyone was accusing everyone of being a liar, I came up with a fortune that said, ‘Don’t run for president, you’re not a good liar,'” he says. But those fortunes are less likely to be approved by the committee of Wonton Food employees who pick the final fortunes, and he also worries that such fortunes will lose their punch as the news evolves.

The company has explored fortune-writing contests and soliciting fortunes online, and they also keep track of diner reactions. A run of brutally honest fortunes about a decade ago didn’t go over well, and authorities briefly investigated the company in 2005, after 110 Powerball lottery players won about $19 million after using the “lucky numbers” on the back of fortunes. Once a jilted wife wrote in to complain that her husband had gotten a fortune promising him romance on his next business trip, and a satisfied customer wrote to say he got a new job after reading a fortune about a new opportunity coming his way.

For Wong, who has a 10-year-old daughter, his new gig is personal.

“I think about what I need to talk to her about,” he said during TIME’s Jan. 18 visit to the factory’s corporate headquarters in the East Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn. “One thing that came to me fairly recently is based on an old Chinese proverb: failure is the mother of success. That’s something that I really want my daughter to embrace — that it’s okay to fail, but if you learn from every failure, you will become successful. Maybe the things I want to say to my daughter will be useful for other people.”

And in the end, Lau believes happy messages make happy customers, while speaking like a practical businessman.

“When they eat their fortune cookie, I want the customers to open the fortune, read it, maybe laugh, and leave the restaurant happy,” he says, “so that they come back again next week.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com