Debbie Reynolds, who died on Dec. 28 at age 84, was a great broad with the face of a cutie pie. You might not know that if you only watched her movies, pictures like The Unsinkable Molly Brown (1964), Tammy and the Bachelor (1957) or, the one for which she’s perhaps best known, Singin’ in the Rain (1952). Reynolds was often cast in roles that capitalized on her cartoon-cherub adorability, her button-nosed brightness, her wind-up energy, all perfectly fine qualities in a performer, and ones that served Reynolds particularly well. But as a real human being — at least to the extent she revealed herself in interviews and in her three books, the most recent of which was last year’s Make ’Em Laugh: Short-Term Memories of Longtime Friends — Reynolds never came off as guileless or naive. She was many things — singer, actress, hoofer, comedian, trouper, mother — but never a pushover.

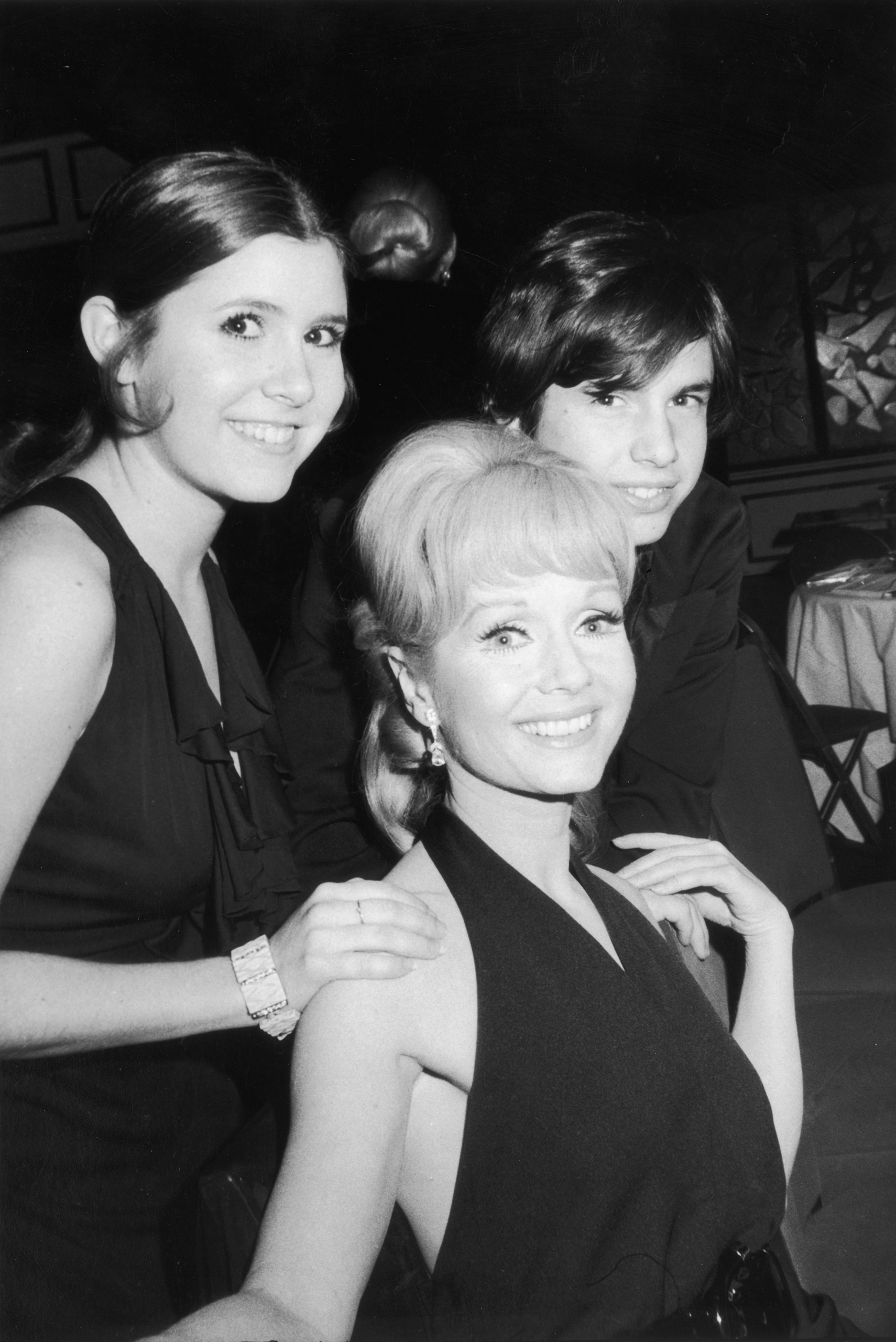

Reynolds, who had moved with her family from her birthplace, El Paso, Texas, to California at age 7, was discovered in 1948 at age 16, when she won the title of Miss Burbank. If the ensuing contract with Warner Bros. was the stuff of Hollywood dreams, Reynolds later suffered through more than her share of Hollywood scandal too. In 1958 her husband of three years — and the father of her two children, Carrie Fisher and Todd Fisher — left her for Elizabeth Taylor. (Reynolds, Fisher, Taylor and Mike Todd, Taylor’s husband until his death in a plane crash in 1958, had been close friends for years.) Publicly, Reynolds was cast in the role of the innocent, wronged woman, a view that meshed with the types of characters she’d played in movies. Everybody loves a victim.

But Reynolds was much tougher than most people would have assumed at the time. In 2011, she and Carrie Fisher gave an interview to Oprah Winfrey, and by that time, Reynolds had spun whatever pain she might have felt into a comically acidic anecdote. At one point, Reynolds, in Los Angeles, needed to reach her philandering husband. When she got no answer at his New York hotel room, she rang up Taylor’s room, and he answered. Reynolds could hear Taylor in the background, asking who was on the line, and said to her husband — with implied exasperation more than livid anger, “Would you just roll over and put Elizabeth on the phone?”

Debbie Reynolds: A Life in Photos

That story tells you something about the complicated and funny person Reynolds must have been, traits she clearly passed on to daughter Carrie, who died Dec. 27. According to Todd Fisher, Reynolds was planning her daughter’s funeral when she suffered a stroke. She died a few hours later. It’s hard not to read Reynolds’ timing as the ultimate expression of grief. The natural order is that children should outlive their parents. That it doesn’t always work that way is a piercing reminder that there really is no natural order to life, although that very unpredictability can bring joy as well as sorrow.

Who could have written a mother-daughter story like that of Reynolds and Fisher? If a writer invented tried, you wouldn’t buy it. Fisher told some version of that story in her 1987 novel Postcards From the Edge, and she revisited it in later books, particularly in 2009’s Wishful Drinking, which she later adapted into a one-woman show. The show, in particular, is like a guided tour through Reynolds’ life, narrated by a daughter who sometimes found her mother a tremendous pain in the ass (the two barely spoke for 10 years, around the time Fisher was in her 20s) but who ultimately saw the woman’s greatest qualities more clearly than anyone.

In the show, Fisher told the story of her parents’ breakups not just from the point of view of the abandoned daughter, but from the painfully adult position of recognizing exactly how much her mother suffered — and how resolutely she picked up the pieces and kept moving. A few years after Eddie Fisher, there was another, possibly worse husband, Harry Karl, a multimillionaire who gambled away all of his money and much of Reynolds’. In the show, Fisher described Karl as “distinguished looking.” As she clarified to Oprah, “When they’re rich and ugly, they’re distinguished looking.” Oprah laughed at that line, but not harder than Reynolds did.

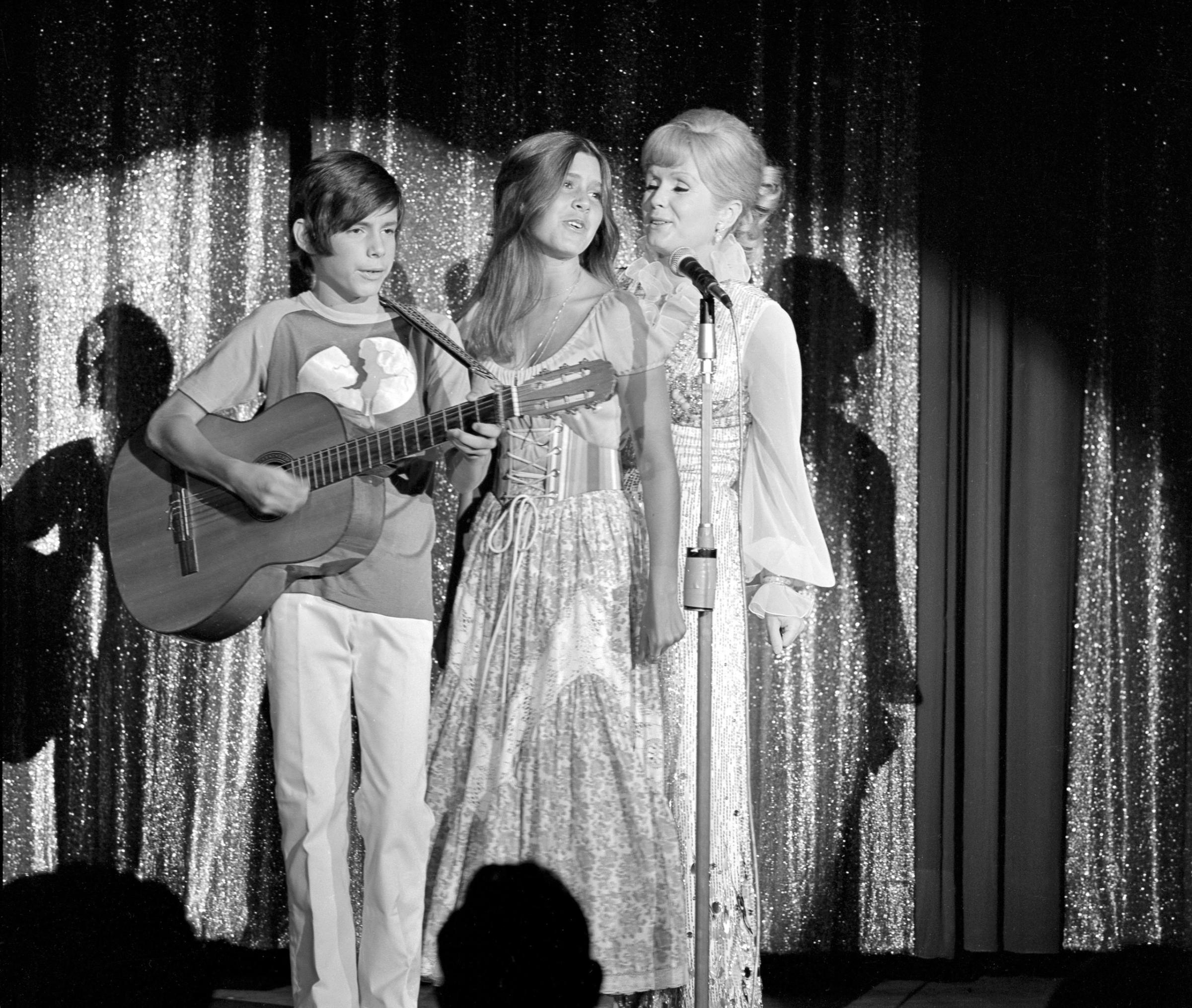

In that interview Fisher also said, before her mother joined her onstage, that as the daughter of a very famous mother, she had never wanted to be in show business: “The scary thing about it is watching celebrity fade. You’re part of their audience.” By the time Reynolds had reached her early 40s, Fisher said, she was no longer wanted in movies. She did bounce back, appearing in, among other pictures, Albert Brook’s 1996 comedy Mother. She also found some fulfillment that refuge of the aging performer, doing cartoon voiceovers for movie and television. (She was the gentle, resonant voice of Charlotte the spider in the 1973 animated version of Charlotte’s Web.)

But, as Fisher has intimated in many ways over the years, Reynolds’ roles of mother and performer were intertwined in a kind of unbreakable wholeness. In that Oprah interview, Fisher described her mother’s closet, with pants and comfortable shoes — mom clothes — at one end and glamorous gowns and dresses at the other: “She’d go in one end as my mom and come out the other … as Debbie Reynolds,” she recalled. People often talk about drawing strength and inspiration from their parents, which Fisher obviously did. But let’s not forget that Fisher was a constant in her mother’s life, too: every time a man let her down, Fisher was there. It’s not overly romantic to suggest that Reynolds lost some essential spark after her daughter’s death. Her rock was gone. Maybe it was time for this great broad to let go.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com