As the children are nestled all snug in their beds this Christmas Eve, visions of sugarplums will probably not be dancing in their heads. The candy landscape of modern America is vastly different than it was back in 1823, the year Clement Moore first published his famous holiday poem known as “The Night Before Christmas.” The once immensely popular sugarplum is now almost completely absent from confectionery shelves.

These days, the poem is more likely to prompt a question than a vision: what exactly is a sugarplum and, almost more importantly, why was it doing so much dancing back in the early 19th century?

Although there is some debate amongst candy historians about this, the term “sugarplum” most likely had some literal truth to it in its early history. Like smoking and salting, sugaring foods has long been an excellent method of preservation. Boiling a fruit with sugar water, or doing the same for a root or flower or seed or vegetable or anything else edible and perishable, considerably extends its shelf life. In defense of the idea of an actual sugared plum, the 1609 cookbook Delights for Ladies in fact calls this process of boiling fruits with sugar “the most kindely way to preserve plums.”

According to author Tim Richardson, however, the term sugarplum was “never confined to preserved plums alone.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

By the 16th century in England, the word referred to almost anything sweet and round, such as a poached fruit or a confection of minced and dried fruit rolled with nuts. Although many centuries removed from the original sweetmeats, these dried fruit and nut concoctions are what legendary food writer Mimi Sheraton describes as “sugarplums” in her 1968 Christmas cookbook Visions of Sugarplums and are what most food bloggers continue to replicate.

But, back in the day, the word sugarplum was also often used interchangeably with the term comfit, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “a sweet consisting of a nut, seed, or other center coated in sugar.” Think Jordan almonds or candied caraway seeds – a single center, surrounded by a hard and crunchy candy coating. (Also often interchangeable: the spellings of the word, and whether “sugarplum” is one word or two.)

Such confections are produced in an incredibly labor- and time-intensive process called “panning,” where layer after layer of sugar is poured over a nut or a seed and allowed to harden. Before the industrial revolution and the advent of automation, it could take a candy maker several days to complete a single batch of comfits. The confection’s price often reflected this, which meant sugarplums were a luxury item worthy of visions, to be enjoyed on a special occasion.

So enticing was the idea of a sugarplum that the term gradually came to describe a great many other enjoyable things outside the confectionery realm. By 1608, again, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, a sugarplum was “something very pleasing or agreeable, esp. when given as a sop or bribe.” A similar definition pops up again in 1788, this time as a verb meaning “to reward or pacify with sweetmeats; hence, to pet, cosset.” A rich person in 18th century England was sometimes referred to as a “plum” while someone else receiving a particularly coveted appointment was considered to have a “plum job.”

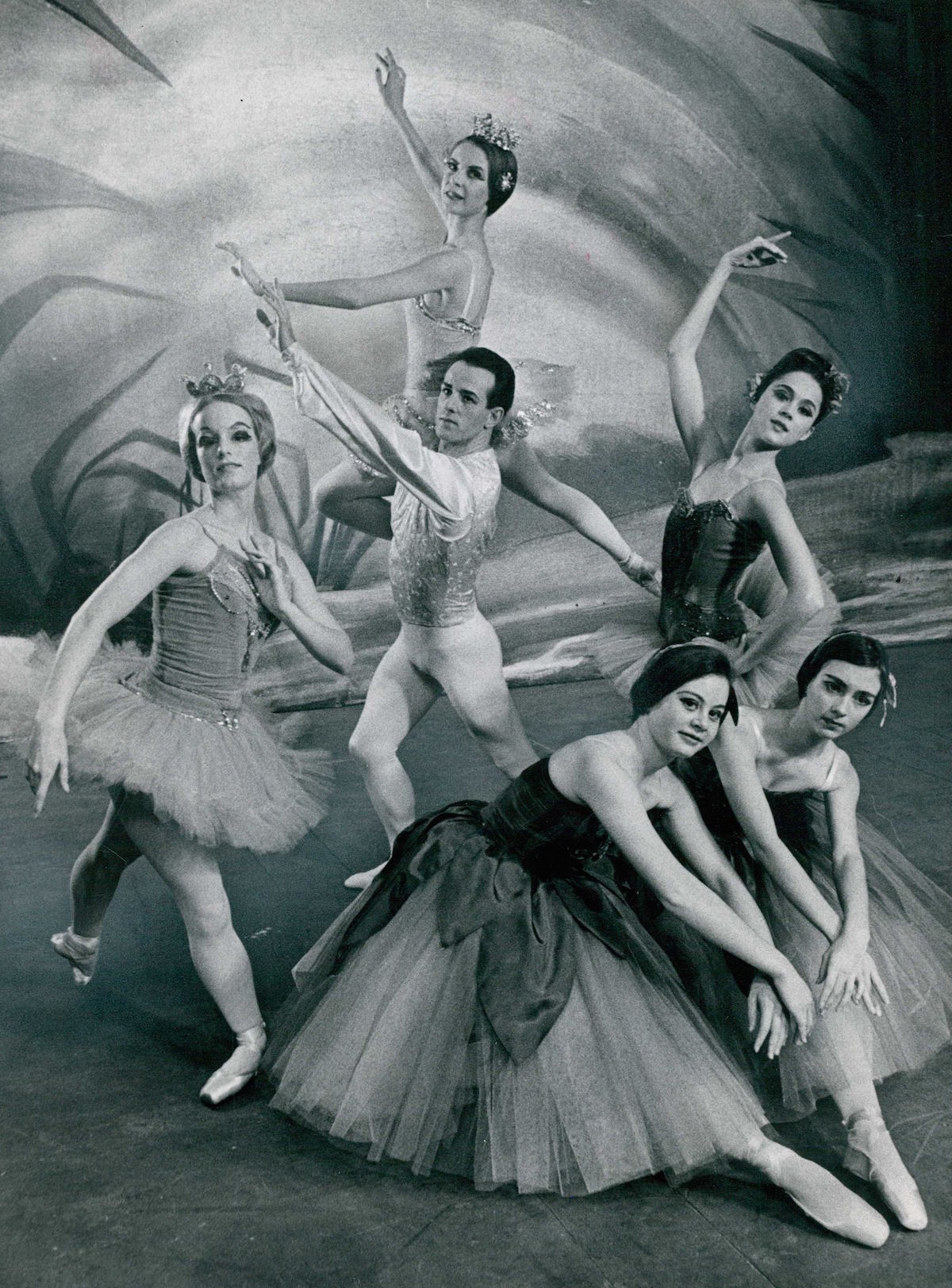

The universality of sugarplums got a second boost by the mid-19th century when factories began mass-producing once labor-intensive foods like comfits. The term “sugarplum” was then expanded even more to encompass almost any kind of sugar candy or bite-sized confection. So, with a name that refers to anything and everything sweet and wonderful in the world, it makes sense then that the Sugar Plum Fairy is chosen to rule the Land of Sweets while the Prince is away in Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker.

It was this broad reach of the concept of a sugarplum that most likely led to its demise, however. The term described every candy and yet no candy in particular, so when marketing gurus transformed crunchy coated sweets into M&Ms and slabs of chocolate into Hershey’s, the sugarplum had nowhere to stick.

Today, more than a century after its heyday, the word sugarplum is considered “obsolete” and not a glimpse of the item can be found on candy-store shelves. But that doesn’t stop the idea of a sugarplum conjuring up visions of yuletide joy every Christmas season.

Emelyn Rude is a food historian and the author of Tastes Like Chicken, available now.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com