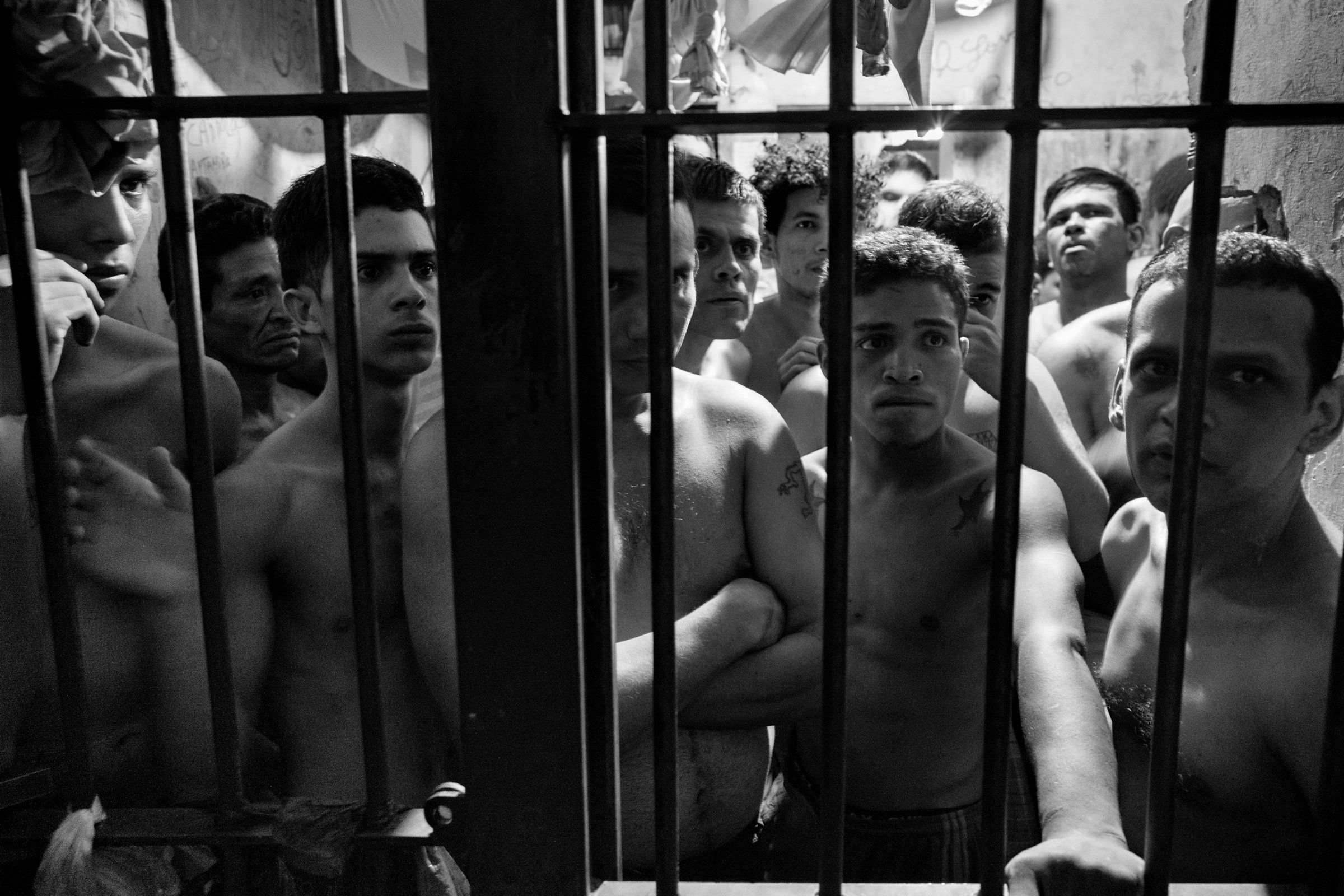

Inside the lockup of the Chacao district police station in eastern Caracas, a mass of prisoners stand shirtless against each other, struggling to breathe amid seething heat and the smell of sweat and feces. The cells here are built for 36 inmates to be held up to three days, before being released or transferred to a larger prison facility. But thanks to a profound crisis in Venezuela’s judicial system, it now holds over 150 prisoners, some who have been here for months or years. The number grows daily as more Venezuelans are arrested for crimes, including mugging, kidnapping and murder. In the most crowded cell, prisoners have no room to even sit down, and take turns resting on sheets tied to bars like hammocks.

Read More: These 5 Facts Explain Why Venezuela Could Be on the Brink of Collapse

The police station is rife with disease. Several prisoners show red lumpy rashes on their skin, a sign of contagious scabies; one coughs from tuberculosis; another is HIV positive. With a medical crisis in Venezuela, most are getting no treatment for these ailments, and with a food crisis, many are malnourished. Widespread water shortages mean the prisoners get access to water only one hour per day. They urinate and excrete in plastic bags and bottles and wait for the guards to collect them.

“In these conditions, your mind deteriorates. You have to shut down parts of it to survive,” says Daniel Sayago, 24, wrestling his way through the bodies to able to get the bars and speak. After being arrested for mugging, he has been in the lockup for one year and four months, while conditions have gotten steadily worse. “You stop being the same person. You become somebody else.”

While all Venezuelan society feels the nation’s economic and political crisis—the country’s economy is poised to contract by 10% this year—the police station lockups, known as calabozos, are perhaps the most acute example of how the South American nation is nearing total collapse. Prisoners at some lockups have erupted into riots, including one at a national police facility several days ago, providing yet another fire for the government of President Nicolas Maduro to put out. Maduro also faces daily outbreaks of looting, food riots, hunger strikes and marches across Venezuela. The opposition, who control the nation’s congress, are calling for a referendum on Maduro’s rule, which could end 17 years of government by the socialist party founded by his popular predecessor Hugo Chavez.

Read More: Venezuela Goes from Bad to Catastrophe

Venezuelan prisons have never been pleasant, but the conditions have been worsened by a violent crime wave that is overwhelming the judicial system. According to the government, there were a stunning 18,000 murders last year in Venezuela, while an independent group claims there were really almost 28,000 killings. The nation’s larger prison facilities are at breaking point, with 52,000 inmates in penitentiaries designed for 20,000, according the Window to Liberty human rights group. Violence inside these prisons claims hundreds of lives a year.

With the major penitentiaries boiling over, the courts leave thousands of inmates in the police station lockups like that in Chacao. Across Venezuela, there are about 20,000 inmates in the police cells designed for 5,000 prisoners, according to Window to Liberty. An energy shortage has added to the problem; in April, all government officials were ordered to work a two day week to save power, slowing down court cases even more.

Read More: Venezuela’s Murder Epidemic Rages on Amid State of Emergency

Ramon Muchacho, the mayor of Chacao, says he is trying desperately to move inmates out of the lockup into larger penitentiaries, but the prison authorities won’t take them. “What we have here is a massive violation of human rights,” Muchacho said. “The country is insensitive to prisoners as we have so many problems and many of these guys were probably criminals. But these are human beings. And this can end in a tragedy.” Even as Muchacho was speaking to TIME in a Chacao restaurant, police arrested a man just outside for mugging. “This is another person we will have to take to the calabozo,” Muchacho said. The man cried on the sidewalk in police cuffs, claiming that he was robbing to feed his starving family.

The lack of medicine in Venezuela—the collapse of the bolivar has made it impossible to import drugs from abroad—affects the mental as well as physical conditions of the prisoners. In the Chacao lockup, Erlinson Solorzano, 24, says he has a psychotic condition, which he treats with various pills, including the drug clonazepam. Until two weeks ago, his mother would bring him the medicine, but she is no longer able to find it in Venezuela’s pharmacies. “I am in real pain here,” Solorzano said. “I am having panic attacks. When I go crazy, my cellmates have to tie me up.”

Some prisoners can’t take it anymore. Last week, a group of 45 inmates managed to break out of a police cell in the Independencia district, on the outskirts of Caracas, before they were recaptured. And over the weekend, prisoners at a national police base in Caracas with about 600 inmates held three officers hostage, demanding they be moved to a less crowded facility. On Sunday, hundreds of family members supported the protest from outside the base. “It is an underworld in there,” said Olga Alvarez, the mother of one prisoner. “Their rights are violated everyday.”

For many Venezuelans, the solution to the judicial crisis and other problems can only be found with a change of government. But the horrific conditions in police cells and prisons also serve as a deterrent to people protesting. There are currently about 120 prisoners in Venezuela who has been arrested on political protests. According to activist Jesus Gomez, about 30 percent of these prisoners have been tortured in police cells or prisons. “It is no secret that there is torture in Venezuelan jails,” Gomez said. “This is a tactic to scare people into submission.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com