At the Bello Monte morgue in Caracas, the smell of death reeks out from the buildings to the surrounding streets and to the dozens of people waiting on the sidewalks to collect the corpses of their loved ones. The odor of the rotting bodies is so strong because of power cuts hitting the air conditioning and the sheer number of cadavers. Every half hour or so, ambulances arrive with new corpses, the vast majority of them homicide victims. The morgue serves the whole of Caracas, which has become one of the most murderous cities on the planet.

“The violence has got worse and worse. It is a devastating situation. There are killers everywhere,” said Jose Medina, a 51-year-old musician, who was sat outside the morgue, waiting to collect the body of his cousin. Gunmen had shot his cousin dead in a taxi he drove in an apparent robbery, Medina said. “It has got dangerous to just be on the street. Many of us stay indoors at night, imposing a curfew on ourselves.”

The country’s runaway murder rate is just one of the factors driving opposition to President Nicolas Maduro in a country where shortages of food and basic goods are chronic, inflation is running rampant and the government is jailing political prisoners. But it serves as a bloody illustration of just how close to outright societal collapse Venezuela has come since the end of the 20th century, as gangs, guerrillas and militia defend their turfs and traditional authority structures fall by the wayside.

The plague of killings

There is fierce debate about exactly how many people are murdered in Venezuela, but all sources find sky-high rates. The government says there were almost 18,000 murders in this South American nation last year, giving it a rate of 58 homicides per 100,000 – compared to 4 in the United States. The independent Venezuelan Violence Observatory claims there were really almost 28,000 murders. An annual comparative survey classified Caracas as the most homicidal city outside a declared warzone in 2015, with 119 homicides per 100,000.

Against this backdrop, opposition leaders are attempting to bring to an end 17 years of rule by the socialist party of the late Hugo Chavez. This month, opposition leaders, who now control the congress, presented almost two million signatures for a referendum on Maduro’s rule. A survey found more than 60 percent of Venezuelans said they would vote him out, and only 28 percent would vote for him to continue.

The Venezuelan government has so far stalled on acting on the petition, while Maduro has declared a state of emergency and claimed dark forces are trying to destabilize the country. “We are victims of the worst media, political and diplomatic threats to our country in the last ten years,” Maduro said Tuesday. Opposition leaders have called on Venezuelans to ignore the state of emergency and march in support of the referendum.

The descent began almost twenty years ago. When Chavez took power in Venezuela in 1999 and launched his so-called “Bolivarian revolution,” he echoed the socialist programs of socialist ally Cuba in investing in poorer communities, running literacy campaigns and setting up health clinics with Cuban doctors. More equality, he hoped, would lead to less crime — as it has in the island nation, which has a homicide rate similar to that of the United States.

But in Cuba, the Castro government tamped down violence by building a powerful, heavy-handed police force and clamping down on illegal guns. In Venezuela, by contrast, Chavez criticized the police for being repressive, while his hardcore supporters formed their own armed groups ostensibly to fight crime. Roberto Briceno, a sociologist who heads the Venezuelan Violence Observatory, says the tactic weakened law enforcement and led to increasing chaos on the streets. “There has been a destruction of the institutions, a breaking of social rules,” Briceno says. “There are armed groups the police know they can’t touch.”

At the same time, Venezuela has seen the growth of the criminal gangs that plague much of Latin America, and other armed political forces, from both the left and right. There are drug cartels with links to the security forces, several leftist guerrilla groups, right wing paramilitary forces opposed to the socialist government, and heavily-armed street gangs. This tangle of competing gunmen has proven a lethal cocktail. In Chavez’s first year of rule, the observatory counted close to 6,000 homicides in Venezuela. In 2013, the year Chavez died and his hand-picked successor Maduro took over, it counted more than 24,000 – rising to the nearly 28,000 it tallied last year.

The drug gangs

Many poor barrios in Caracas and across Venezuela have seen an expansion of street gangs, who sell drugs, carry out armed robberies and commit heinous amounts of murders. Unlike the cartel armies of Mexico, the Venezuelan gangs often have just a few dozen members and control a few blocks. But they possess potent weaponry including fragmentation grenades, automatic rifles and even anti-tank guns.

In a slum known for drug selling in west central Caracas, a gang leader known as El Gocho agreed to talk to TIME. At 40 years old, Gocho has been in gangs since he was 15, saying he first made money selling drugs so that he could support his mother. He now heads about 30 cohorts hawking packets of cocaine along several streets, which are known as good trafficking real estate.

As he controls a profitable business in a country going through a severe economic crisis, he says he is constantly dealing with rival gangsters trying to invade his turf. “There are crazy people out there trying to kill me all the time, and take over this area. People who want to cut you up in pieces and burn your body with gasoline,” he said. “That is why we need to have big guns to defend ourselves, and watch whoever is coming into this area.”

Similar gangs crisscross Caracas, creating frontlines between rivals every few blocks, and Gocho says he faces enemies on all sides. He has bullet wounds from several shootings that he survived and admits to killing various rival gangsters.

Gocho says he buys the cocaine wholesale from Colombians operating in Caracas and sells it in small packets to users. Venezuela rarely produces its own cocaine, but Colombian traffickers have been arrested here, using the country as a transit route for drugs going to Europe and the United States as well as selling locally.

The traffickers sometimes work with Venezuelan officials. In February, a Venezuelan army major was arrested with 503 kilos of cocaine. Even more controversially in November, police in Haiti working with agents from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration arrested a nephew and stepson of President Maduro himself on drug charges. They are currently in the United States where they have pleaded innocence.

The Chavista collectives

A few miles through Caracas in another poor barrio, the head of a “pro-Chavista” group who calls himself Comandante Cienfuegos sits in a heavily armored bunker. A muscular former paratrooper, Cienfuegos asked not to use his real name as he also confessed to carrying out murders, saying that he kills criminals who sell drugs or steal in his neighborhood.

“That is the way we deal with this scum. We go out there with guns and masks on and eliminate the threat,” Cienfuegos said, sitting in front of a mural of revolutionary Che Guevara. “We are the worst nightmare of these rats.”

Cienfuegos was a longtime supporter of Chavez, who he refers to as “our father creator.” In 1992, while a paratrooper, Cienfuegos joined Chavez in his attempted coup against then President Carlos Andres Perez. When the coup failed he served three months in prison; Chavez himself was incarcerated for two years before he was released and went on to win the presidency.

When supporters of Chavez formed the armed community groups, known as collectives, the socialist government largely tolerated them, rarely seizing their guns or raiding their bunkers. Cienfuegos claims there are now about 8,000 such militants in Venezuela, mostly in the Caracas area, although there is no official registry.

Cienfuegos personally commands about 40 cohorts to operate their alternative policing of his barrio. He says they will first warn a criminal or break their legs, but if they keep committing crime they will “execute” them. He says that local businesses pay them to keep the criminals out. “They are happy for us to be here. The police don’t keep the barrio clean so we are needed,” he said. Opponents of the collectives say it is more akin to extortion.

Cienfuegos sympathizes with the various leftist guerrilla groups in Venezuela, including the Bolivarian Liberation Force, or FBL. While operating illegally, the FBL supports the socialist government. On the other side, he is on red alert for right wing paramilitaries, who have spilled over from neighboring Colombia.

Several Colombian paramilitary figures have been arrested in Venezuela, and the government claims they are a growing force, extorting businesses and murdering socialist organizers. The paramilitaries, “are financed with money from hard drugs, with dollars, to bring war to all the urban communities in the principal cities of our country,” Maduro said last week.

The lawmen

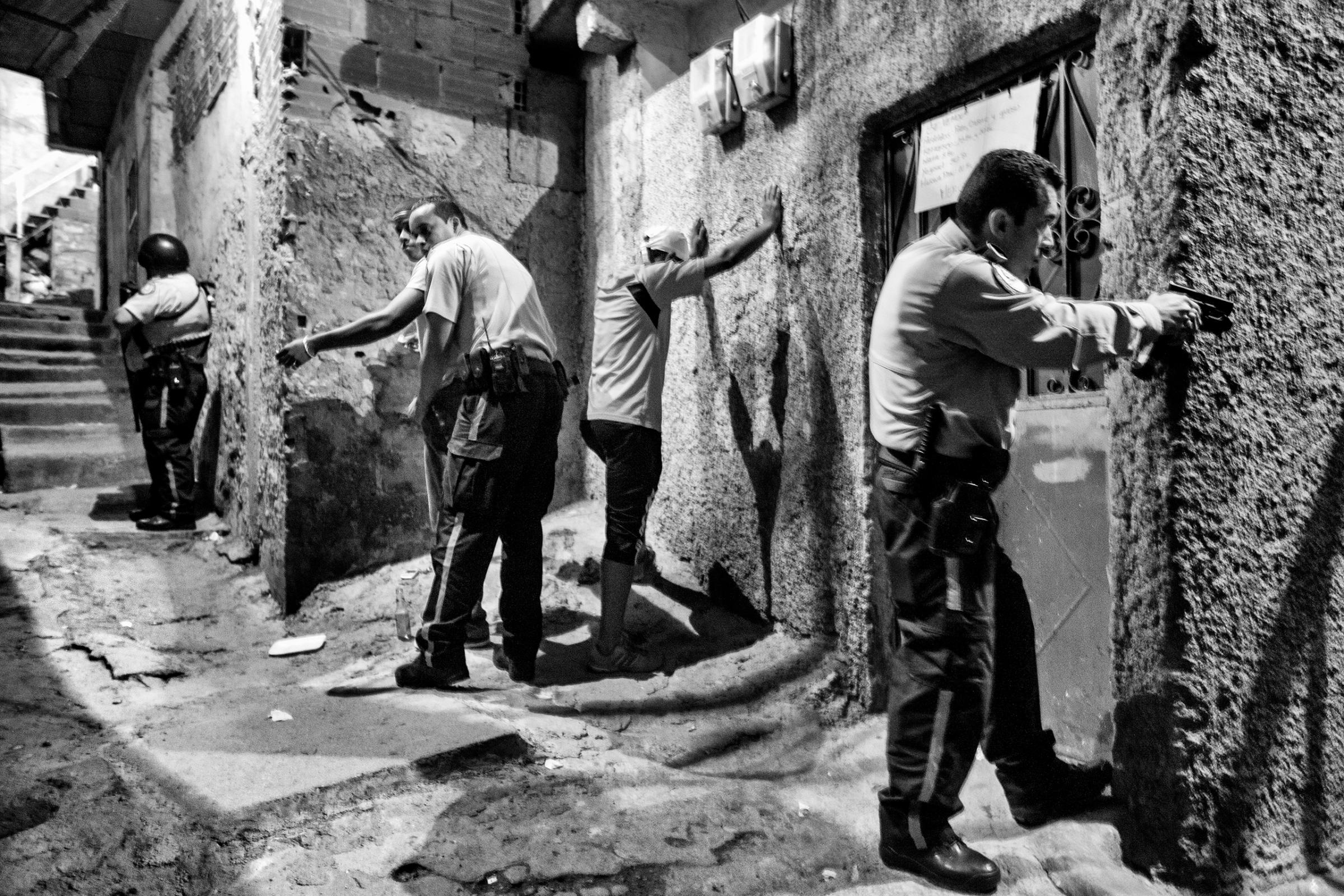

In the midst so many competing gunmen, the police struggle to keep control on the murderous streets. TIME rode with a unit from Miranda State police patrolling the violent Petare slum on the outskirts of Caracas to see officers on motorcycles in light bulletproof jackets, which offer little protection against the high-caliber bullets used by many gang members. The chaotic slum is built on a steep hill and riddled with alleys, providing many points for gang members to fire on officers or ambush them.

“You have to trust in God that you are going to make it home safe,” said the night commander Jhoni Nava, who headed the unit. “It is a tough job.”

A small command post high up in the slum showed the photo of a fallen comrade, with prayers to him written beneath. More than 330 police officers were murdered across Venezuela last year, according to counts by human rights groups.

However, human rights defenders say the police do plenty of killing of their own. The Violence Observatory estimates that officers shot dead about 3,800 people last year, which would make them one of the most homicidal forces in the world.

Antonio Gonzalez, an academic who has worked with the socialist government on police reform, agrees there is a very high rate of police killings. “Part of the problem is that many individual police officers are corrupt,” he said. “The government has made good changes to the police regulations but they often aren’t put into practice. The police force still operates in a classist way, using more violence against the poor.”

Gonzalez agrees with the opposition that there has been a breakdown of law and order in Venezuela, but blames the opposition themselves for fomenting it. In 2002, there was an attempted coup against Chavez and in 2014, thousands of opponents of the government built barricades on the streets, leading to armed confrontations.

With the government stalling on the referendum, more such confrontations could beckon, exasperating the violence further. And even if the opposition manage to vote Maduro out of power, it will take a Herculean effort to prevent more corpses piling up at the morgues of Venezuela.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com