Founded in 1925, the Scripps National Spelling Bee prepares to crown its 2016 champion live on ESPN this Thursday. TIME talked with eight former champions from the long history of the bee to see what they did next, where they are today and how the study prep for bees helped them get there. Most of these well-rounded professionals described the moment of victory as their 15 minutes of fame, but some did say their winning words have come up throughout their lives in the most unexpected and hilarious ways. Here are their stories:

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

1954

Name: William Cashore, 76, East Greenwich, R.I.

Winning word: Transept (n. “the section forming the short arm of a church with a cross-shaped floor plan”)

Occupation: Neonatology specialist and professor emeritus at Brown University’s Alpert Medical School

Nicknamed “speller” in high school, he was pre-med at the University of Notre Dame and went to the University of Pennsylvania for medical school. He credits the spelling bee with giving him the confidence to compete and to speak out in public, which came in handy for teaching and lecturing later in life. Correctly spelling the championship word even inspired a lifelong interest in architecture.

“I’m a fan of period styles of architecture. Walking into a church in Europe,” he says, “I’ll say, ‘Here’s the transept, the nave, the apse, et cetera.”

A few years ago, he came in second in a charity spelling bee with hospital co-workers—but he blames his ears, not his spelling chops for his runner-up status: “I had developed a bit of hearing loss. I couldn’t always hear the words quite clearly.”

1978

Name: Peg McCarthy, 51, Topeka, Kans.

Winning word: Deification (n. “the act or an instance of deifying,” meaning “to make a god of;” “the process of becoming one with a deity”)

Occupation: Clinical psychologist

The National Merit Scholar and a U.S. Presidential Scholar—who had never been on a plane before the spelling bee—became the first member of her family to go to college outside of Kansas when she earned a B.A. in English from Yale University. Then she worked the bee’s network of newspaper connections to land a job as a copy editor at the former Albuquerque Tribune, before going on to get her M.A. and Ph.D in Clinical Psychology from the University of Kansas, where she met her husband in the first week of classes. They’ve had three sons — two of whom won county bees. Now she has a part-time private practice in Topeka, serves on its school board and runs a support group for transgender teenagers.

Since she lived in the area for much of her life, she has become a local celebrity, and has helped out with local spelling bee contests, even coaching a student who made it to the national bee twice. She sees storytelling as the link between studying etymology—the stories behind words—and what came after: “That’s probably the unifying element from getting an English major to working for a newspaper to being a therapist,” she says. “That’s what psychotherapy is all about.”

1982

Name: Molly (Dieveney) Baker, 46, Wayne, Penn.

Winning word: psoriasis (n. “a chronic skin disease characterized by circumscribed red patches covered with white scales”)

Occupation: Chief operating officer and writer at an investment management firm

This champion majored in East Asian Studies (with a Chinese concentration) at Yale University, before working in investment banking at Credit Suisse First Boston and then as a reporter at the Wall Street Journal. After getting a MFA in nonfiction writing, she shadowed a mutual fund team and published High-Flying Adventures in the Stock Market. She then freelanced for the Journal and the Philadelphia Inquirer and blogged about life as a wife and mother of three boys on her parenting site “Playgroup with Sylvia Plath.”

She was encouraged to start competing in spelling bees by her next-door neighbor growing up in Denver, Colo., Jacques Bailey, the 1980 champion who’s now the national bee’s official pronouncer.

And turns out the word she had to spell to become champion came back to haunt her nearly 20 years later in the most literal way possible. “I got a skin biopsy after I had kids,” she says. “The doctor called me back in a week later and said, ‘It turns out you have psoriasis.’ I burst out laughing.”

1984

Name: Dan Greenblatt, 45, San Francisco, Calif.

Winning word: Luge (n. “a small sled used for racing down an ice track”)

Occupation: Software engineer and voice actor

While the Virginia native had “fun hanging out with like-minded weirdos like me” at the national competition, he found the victory lap afterwards not as fun. All of TV appearances in D.C., NYC, and L.A. — where he had a spell-off with Johnny Carson — made him less interested in staying famous.

“I saw what people had to go through, between the news media crushing you and having to fly everywhere and have these conversations with people you don’t know,” he says. “It’s a wake up call for people who think, ‘When I become rich and famous, my life will change, and it’s all going to be wonderful, and I’ll live like Kim Kardashian.’ I work much better behind the scenes.”

Greenblatt went on to study computer science at the college and master’s level at William and Mary and James Madison University, respectively. Now he works at a startup by day and does voice acting for radio ads and video games by night.

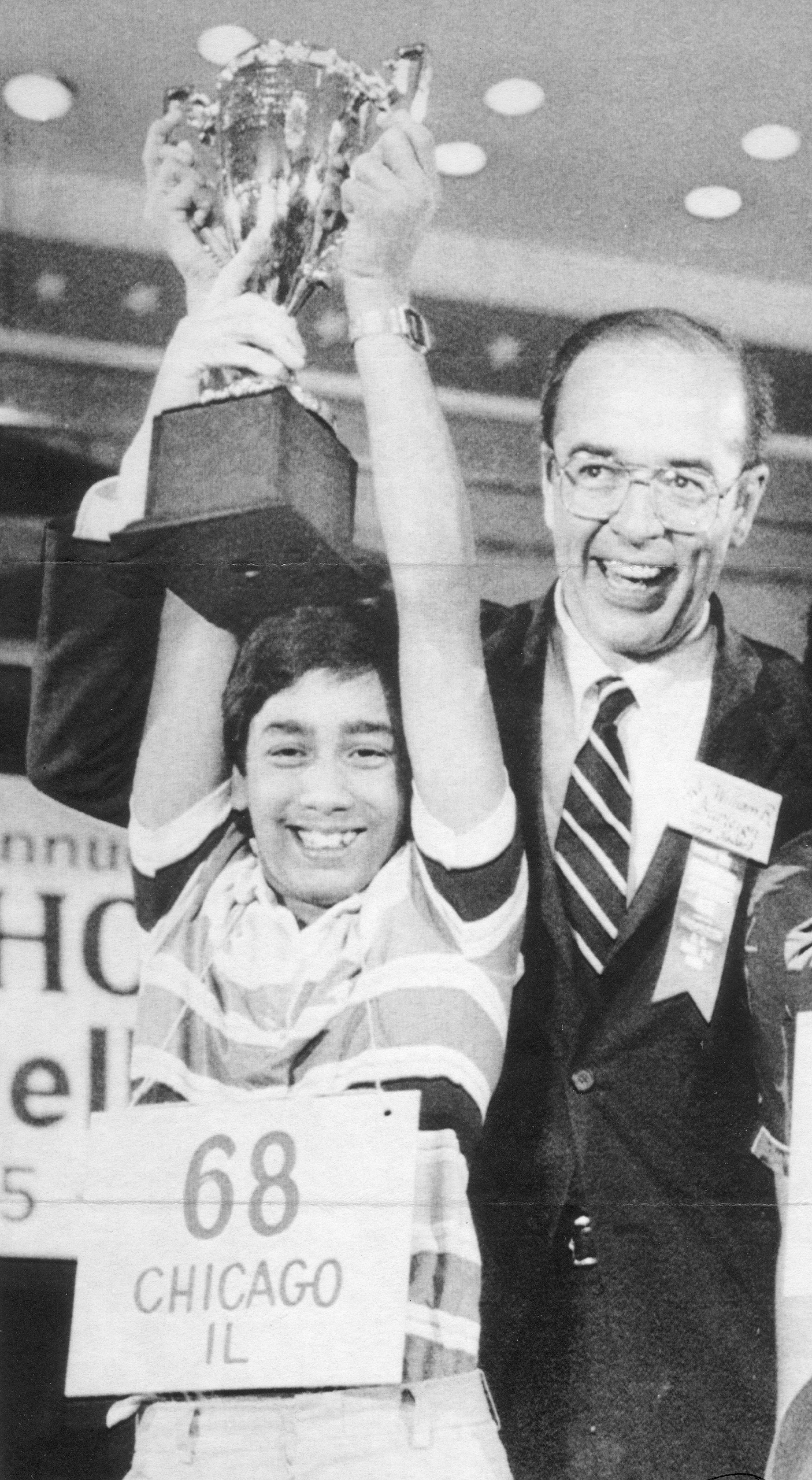

1985

Name: Balu Natarajan, 44, Hinsdale, Ill.

Winning word: milieu (n. “the physical or social setting in which something occurs or develops”)

Occupation: Chief Medical Officer of Seasons Hospice and Palliative Care, who also has a private practice focused on internal medicine and sports medicine

As someone who went to the National Spelling Bee twice before winning it on the third try, it’s no surprise that Natarajan’s niche within his practice became helping marathoners and triathletes: “Competing in the National Spelling Bee is really a marathon and not a sprint. It takes years for most of the kids to hold up that trophy or make it to the national competition. That’s what allowed me to have an appreciation for endurance athletes and enjoy taking care of them.”

So many patients have asked whether he really won the bee and whether he was really in the 2002 spelling bee documentary Spellbound that he added those tidbits to the FAQ section of the website for his practice. And because his championship word is a commonly used one, it easily became an “inside joke” among other doctors. “Every time I would be covering for a fellow internist on weekends, he would write ‘milieu’ in regards to a patient in at least one medical chart the day before, so dozens now have that word in them.”

Natarajan also takes pride in being the first Indian-American to win the Scripps National Spelling Bee. “The one thing that my victory did show is that you can be an immigrant and win a competition about the English language.” This year, his two sons have qualified for one hosted by the North South Foundation, which has been called a “minor-league training ground” for South Asian spelling-bee champs. His oldest, Atman, is “really into it,” Natarajan says, and “watching him compete is far more stressful than standing on the stage at the Scripps National Spelling Bee.”

1989

Name: Scott Isaacs, 41, Denver, Colo.

Winning word: spoliator (n. “one that spoliates : spoiler”)

Occupation: Spelling bee coach

When TIME talked to Isaacs nearly ten years ago, he was practicing chiropractic and naturopathic medicine and claimed that his spelling bee championship didn’t really come up much. Then in 2011, a friend told him about a Craigslist ad from a father looking for someone to tutor his son for an upcoming spelling bee. He responded, got the job and sent the youngster to the top 10 of the national spelling bee. “I thought, maybe I got a knack for this,” Isaacs says.

So far he has coached 30 top spellers across the country — including Natarajan’s 10-year-old son — mostly over Skype. Ten have made it to the national bee, and three to the top 10. He is also the academic director for the Spelling Bee of China.

One big difference between past and present bees, he says, is that the words have gotten more difficult, “because spellers these days have much more access to word lists and resources on the Internet.”

1996

Name: Wendy (Guey) Lai, 32, San Francisco, Calif.

Winning word: vivisepulture (n. “The act or practice of burying alive”)

Occupation: Part-time eighth grade math teacher at Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School in Berkeley

The national spelling bee was a family affair for the Florida native, whose older and younger sisters also went to the D.C. competition, so the three would quiz each other on words growing up.

After majoring in Economics at Harvard and working at a bank and a fund of funds, Lai, who came from a family of educators, quickly realized teaching “was in my blood.” So she got a master’s degree in school leadership from Harvard’s graduate school of education and began teaching high school math in Boston public schools.

Studying for spelling bees taught her a few life skills that are especially relevant to teaching: how to be resilient, detail-oriented and exhibit “grace under pressure.” She also likens the process of trying to figure out how to spell an unfamiliar word to the process of trying to solving a math problem: “I don’t like to think about spelling as memorizing a bunch of words, just like kids shouldn’t rely on memorization to do math.”

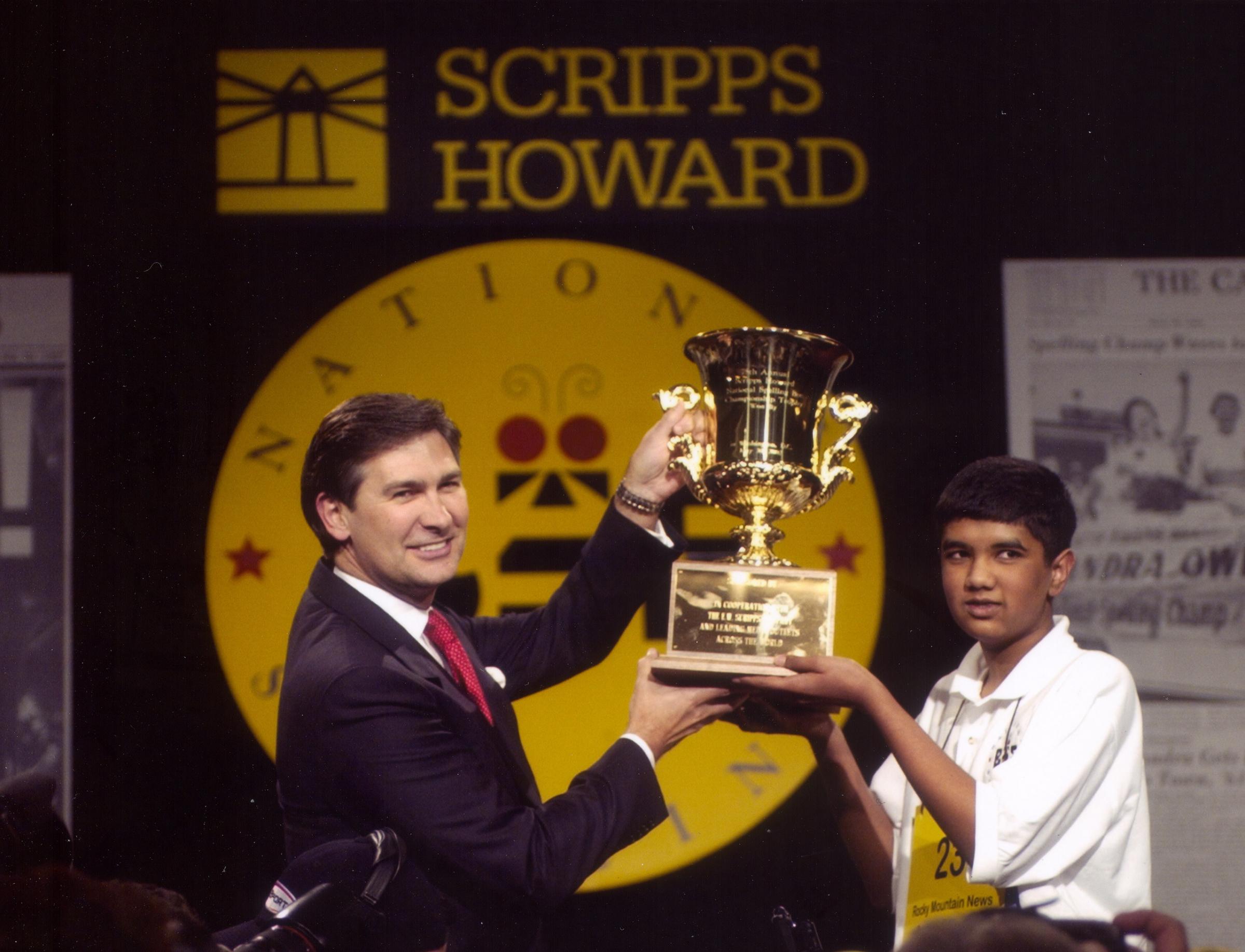

2002

Name: Pratyush Buddiga, 27, Colorado Springs, Colo.

Winning word: Prospicience (n. “the act of looking forward”)

Occupation: Professional poker player

Nearly a decade after winning the $12,000 prize as a Scripps National Spelling Bee champion, Buddiga started winning much larger prizes as as a professional poker player. He started playing seriously during his senior year at Duke University, where he majored in Economics.

“I think I became a professional poker player because I really missed competition,” he told TIME in an email. “I became adept at pattern recognition — root words and trusting my gut instincts on seemingly unfamiliar words — which is valuable for poker as well. The spelling bee also requires a good memory, which is really important for poker as you must remember tendencies of your opponents or little bits of information that may help you in a hand even years later.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com