Nineteenth-century vegetarians were often considered too radical, too naïve, or, simply speaking, wacko. They were called “half-crazed,” “sour-visaged,” “infidels,” and “food cranks.” And, admittedly, some of them had pretty unusual ideas. Over one hundred years before the first hippie communes, Amos Bronson Alcott (the father of Little Women’s Louisa May) started a vegan community in New England, which he named Fruitlands. Alcott actually believed that he was planting the seeds for a Garden of Eden version 2.0 and that Harvard, Massachusetts, was the promised land. Everyone in Fruitlands wore specially designed tunics and lived on plants grown in the commune’s soil—which, by the way, remained unfertilized, because Alcott claimed manure was too filthy. That proved costly, particularly combined with the inhabitants’ lack of agricultural skills. Once the first winter arrived, Fruitlands went bankrupt: the crops had failed, and there was nothing to eat.

But at least Fruitlands did exist for a couple of months. A vegetarian metropolis in Kansas called Octagon City never really took off. The plans were grand: the city was to be sixteen square miles, with an agricultural college and scientific institute, and to support itself by exporting fruits, graham flour, and graham crackers. Yet before Octagon City managed to start exporting anything, the first settlers were chased away by snakes, outlaws, hostile Indians, and . . . mosquitoes.

Such failing, far-out ideas as Fruitlands and Octagon City would have been reason enough to keep the masses from joining the vegetarian movement. But fate handed the critics of vegetarianism an easy weapon: the premature deaths of several of the movement’s leaders. Even though these deaths had little to do with the absence of dietary meat and were the results of tuberculosis, preexisting medical conditions, or poisoning with industrial fumes, the word spread. People started to wonder: maybe vegetarian living wasn’t so healthy after all.

And then came the wars. Despite the nineteenth-century vegetarian movement suffering from some bad press, it was still relatively strong. After all, it did manage to convince many Americans and Britons to remove bacon and sausage from their breakfasts. But the two world wars pushed Western diets firmly back toward meat. To begin with, it’s hard to care for animals when you see so much human suffering around. As one novelist wrote: “These days nobody wept for horses.” Nobody wept for chickens and pigs, either. Besides, if you were an American or a British soldier, you could hardly be a vegetarian. Army rations were heavy on meat, so if you wanted your stomach full, you had little choice but to eat everything up, which most did with pleasure, of course. For the many poor who swelled the military ranks, the newfound abundance of animal protein was a dream come true. They could finally, often for the first time in their lives, eat as much meat as they wanted, meat that for so long had symbolized unreachable power and luxury and that was loaded with umami, fat, and the flavors of the Maillard reaction.

Meanwhile, for American and European civilians, meat was such a rare treat during the wars that it became even more of a status symbol than before. Social psychologists would tell you this was an example of the scarcity principle at work: the less available something is, the more we value it. When a 1940 survey was conducted to find out what Americans craved to eat the most, first place was taken by ham and eggs, followed by prime ribs, chicken, lobster, and baked Virginia ham. No vegetarian dishes made the list.

At the same time, something strange was happening in UK: the numbers of vegetarians-by-choice actually went up during World War II. Did the hardships of war make the British link animal suffering with the human one and inspire them to stop eating meat? Not exactly. What really happened was far more prosaic. In Britain, if you registered as a vegetarian, you were allotted a bigger ration of cheese, much more attractive than the tiny and unreliable meat ration. If you wanted to feed your family, the choice seemed obvious. Yet as soon as pork and beef became available again after the war, all these “vegetarians” were more than happy to sink their knives and forks into meat—probably even more so than before, since the new postwar abundance of meat became a symbol of peace and prosperity.

War scarcity, human suffering that left no place for caring about animals, meat-loaded army rations—that would have been enough to stamp out the vegetarian movement. But it also didn’t help the movement’s PR that Hitler was a vegetarian. Several of the dictator’s biographers wrote about his commitment to a plant-based diet. He was quite a hypochondriac: he mistook stomach cramps for cancer and worried about his muscles trembling. A vegetarian diet was supposed to help preserve his precious health. At the same time, in a move that seems bizarre to many, Hitler outlawed vegetarian societies in the Reich. It wasn’t bizarre at all, though. Not only did the Führer want to set himself apart from the plant-munching weirdos, he also didn’t like the radical, counterculture currents that were part of the vegetarian movement.

As years passed and war scarcities became a distant memory, as new, more scientifically sound studies started showing the benefits of meatless diets, the numbers of vegetarians in the West inched up. Still, just like the Grahamites in the nineteenth century or the Pythagoreans in fifth century BCE, these modern plant eaters were considered outsiders who dared to reject societal norms. As Rags magazine reported in 1971: “To many Americans, vegetarianism represents another weirdo protest of the head generation against mom-and-apple-pie-ism.” But something was different in the ’60s and ’70s: being a weirdo wasn’t so bad anymore. In the era of entertainment media and television, granola-loving hippies were news. They grabbed attention and became a group celebrity. But when the ’70s waned into the ’80s, and consumers tuned their TVs to shows such as Dallas and Dynasty, depicting upscale lifestyles, hippie values lost out to materialism. Whatever symbolized power and strength was good and desirable, whether it was steaks or Patek Philippe watches.

So far Western vegetarians hadn’t managed to unhook humanity from meat.

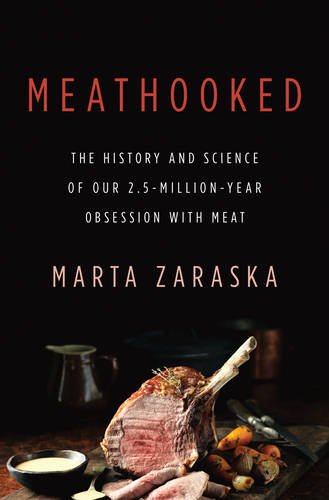

Excerpted from Meathooked: The History and Science of Our 2.5-Million-Year Obsession with Meat by Marta Zaraska. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2016.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com