The news this week that new parents may have started naming their babies after Instagram filters has prompted the predictable round of outrage—but history is full of evidence that there’s no reason to freak out about baby Lux.

Parents following larger cultural trends when looking for baby names is nothing new, says Cleveland Evans, a former president of the American Name Society, an group that promotes onomastics, the academic study of proper names. Even in times of extreme conformity in naming, Evans says, there have always been a few parents who decided to name their babies something that sounded a little more unusual. In fact, many of the names that now seem conventional were once weird or trendy.

“Jessica is basically invented by Shakespeare,” Evans points out. “And most of the flower names, except for Rose and Lily, were only invented in the 19th century, and there were a lot of people who hated them when they first came in. There was actually a prejudice that if you gave your child the name of a flower they would die young.”

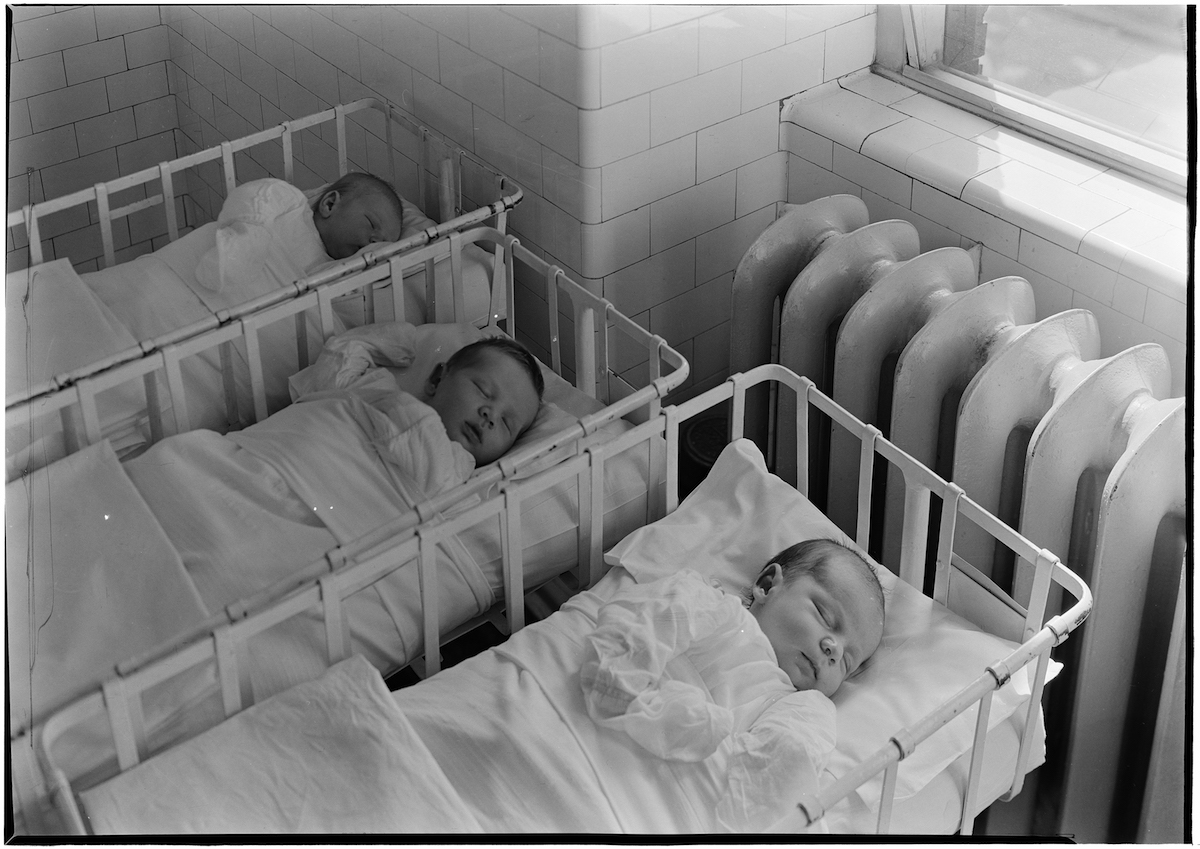

For onomastics experts, looking at those trendy names, or the lack thereof, can be a valuable clue about a period in history. During the post-WWII baby boom, for example, large numbers of children shared the same first names — signaling to historians that the era was one of conformity and assimilation, even more so than the earlier part of the 20th century. (Prior to the 20th century, there was another period of conformity; during the 1830s, Evans says, something like 16% of girls in the U.S. were named Mary.)

Since the mid-20th century, names have indicated a move toward individualism. Historians of the future may well look back at Valencia and Kelvin as crucial clues about life in the U.S. in 2015. “The conformity today is that everybody has to find a different name,” Evans jokes. “People right now who would name a baby Susan or Jennifer are the real non-conformists.”

The other big reason not to be surprised by the “Instagram babies,” Evans says, is that parents today are seek names that are a little more unusual—not a lot. The names that are both Instagram filters and rising in popularity, he says, are “names that in general sound like what is popular for baby names already.” Take Hudson, for example. Yes, it’s an Instagram filter, but it also matches up with the two-syllables-ending-with-N trend that brought us extremely popular names like Jaden, Aiden and Logan. Likewise, Lux is not so far from Max.

It’s very likely, Evans says, that the Instagram name trend is actually about correlation rather than causation. The people naming the filters would have been affected by the same name-sounds trends that the people naming babies are affected by, and filters that don’t already sound like names (Toaster, for example) are unlikely to cross over into the mainstream baby-name pool.

The same phenomenon has shown up in past examples of product names infiltrating baby trends, as with the older wave of children named after automobiles. “Camry is the brand name of a car, but it sounds like a feminine version of Cameron,” Evans says. “Nobody is going to name their kid Oldsmobile.”

Evans even has personal evidence that the trend holds true: his sister decided to name her daughter Ashleigh after seeing that spelling in a wallpaper catalog. The key point is not that his niece is named after wallpaper, but that she’s named after wallpaper that already sounded like a girl’s name. “It wasn’t in a vacuum,” he says. “There’s a back and forth there.”

And there’s one other point from baby-naming history that’s likely to continue to hold true: People have always reacted strongly to new names, whether they’re worried that Daisy is in for an unlucky fate or tweeting about Amaro. That happens for the same reason that many academics are drawn to onomastics. “Names are interesting,” Evans says, “because everybody has one.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com