“When is a sandwich not a sandwich?” asked the intrepid reporters at TIME in April of 1958. As more recent battles over the sandwich-status of the burrito have demonstrated, the question has never been an easy one to answer. (Spoiler: a burrito, according to the United States government in 2006, is in fact not a sandwich.) But more than a half-century ago, the age-old query came with a twist, as the debate raged at 30,000 ft. above the Atlantic.

It was the dawn of the Jet Age, the era when commercial airlines were making air travel accessible to the common man for the first time. But, as it turned out, not that accessible: tickets for Trans-Atlantic routes in the existing First and Tourist classes were, in many cases, prohibitively expensive. So, in an effort to democratize the skies, and to sell more tickets, the airline companies introduced the now all-too-familiar and cheaper “Economy Class” on its trans-Atlantic flights.

Afraid that unbridled competition between carriers would jeopardize the safety and quality of flights for travelers, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) tightly regulated the airline industry at the time. As a result, fares and seating configurations on these new “Austerity” flights, which debuted on April 1, 1958, were standardized across companies. So was the menu airlines were allowed to serve: coffee, tea, mineral water and a few “simple, cold, and inexpensive” sandwiches.

These directions seemed simple enough at first. Then came the sandwiches.

It quickly became clear that different airlines had different interpretations of the word—and that those differences were enough to shake the very foundations of international goodwill.

The first camp was led by the North Americans PanAm and Trans World Airways, which both served up typical American-style sandwiches, such as egg salad, roast beef, or ham and cheese layered between two thick slices of bread.

Their opposition presented sandwiches in the open-faced, European-style. Menus on Scandinavian Air Systems (SAS) flights consisted of items like “five slices of ox tongue, a lettuce heart, asparagus and sliced carrots—on a slice of bread” while Swiss Air provided guests with two dessert sandwiches, “perhaps peach on Zweiback,” after they had finished their assortment of twelve dainty appetizer sandwiches and primary sandwich. KLM Royal Dutch Airlines and Air France too served up similarly extravagant selections.

Needless to say, PanAm and TWA were not pleased with the sumptuous sandwich affairs of the European carriers. Their sandwiches amounted to a three-course meal on bread, the North Americans claimed, a level of luxury that was contrary to the ideals of economy class—and which might sway customers’ airline choices. A spokesman for SwissAir declared in response, “everyman is entitled to his concept of a sandwich and we have ours.” The company, in turn, would “defend [its] sandwiches to the end.”

As the weeks progressed, the discord only continued to grow, with SAS publishing a sales letter declaring to its potential customers, “on our planes you won’t find rubbery indigestibles wrapped in cellophane.” American carriers responded with threats to banish European airlines from American airspace.

As the media latched on to the mounting absurdity of “the Great Sandwich War of 1958,” the IATA stepped in, convening a special meeting in London to determine once and for all what constituted a sandwich in the friendly skies.

To the disappointment of sandwich aficionados everywhere, the IATA sided with PanAm. According to their ruling, a sandwich must be “cold… simple… unadorned… inexpensive,” and must “consist of a substantial and visible chunk of bread.” Any materials “normally regarded as expensive or luxurious, such as smoked salmon, oysters, caviar, lobster, game, asparagus, pate de foie gras,” as well as “overgenerous or lavish helpings which affect the money value of the unit” were prohibited as well. Although most European carriers escaped the affair unscathed, SAS was slapped with a $20,000 fine for its blasphemous slander of indigestibles wrapped in cellophane.

It wasn’t until the deregulation of the airlines in the 1970s that menus started to change and creativity, for better and for worse, returned to the bill of fare for Economy Class. SAS today still serves up sandwiches on its flights, but with demand for cheaper fares overpowering in-flight service, it’s now often up to economy customers to purchase those meals themselves. Although the skies are now indeed more accessible to all, sometimes the current state of dining at 30,000 feet is enough to make one miss the good old days of the Sandwich Wars.

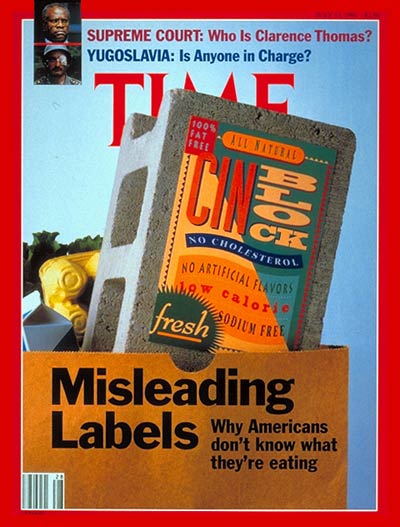

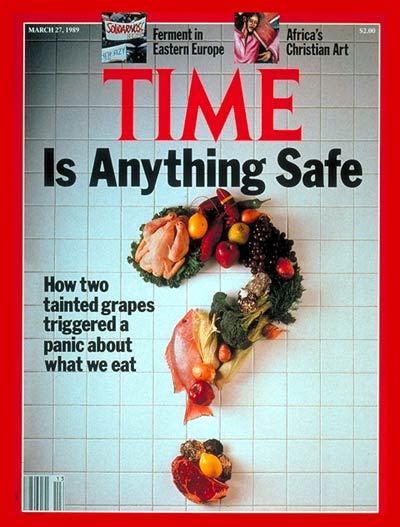

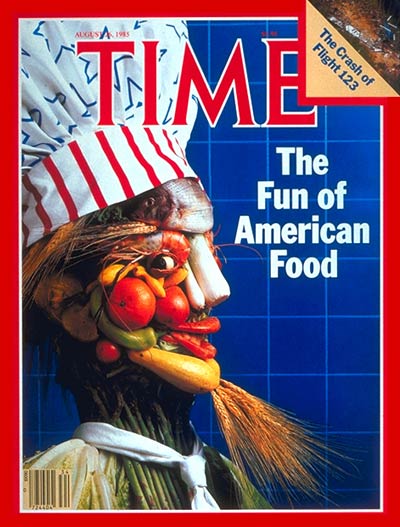

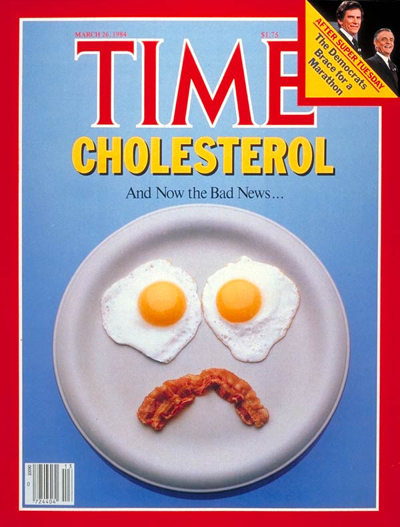

The War on Delicious and 19 Other TIME Magazine Food Covers

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com