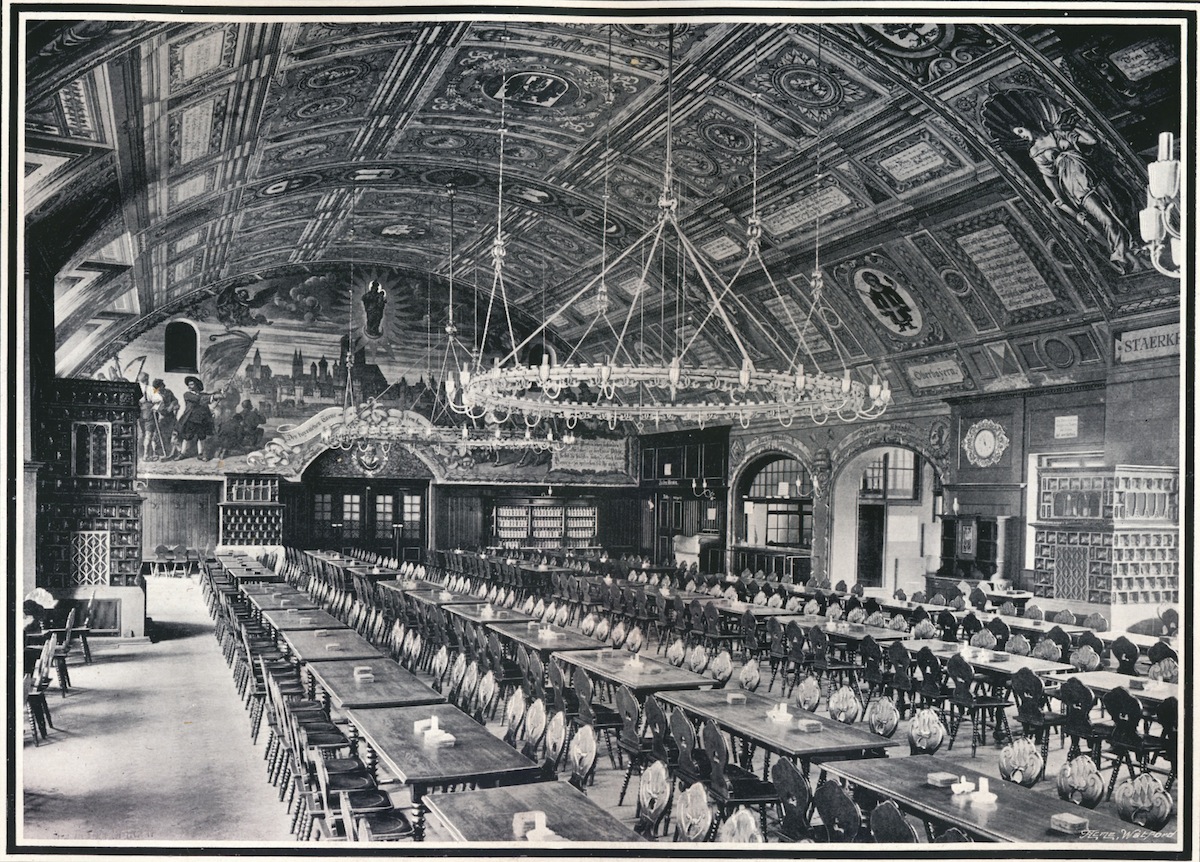

These days, Oktoberfest is a 16-day beer-for-all at Munich’s historic fairgrounds—but when it got its start 105 years ago, it was simply the world’s best wedding reception.

When Bavaria’s Crown Prince Ludwig married Princess Therese of Saxony-Hildburghausen on this day, Oct. 12, in 1810, Munich residents celebrated with horse races and several days of drinking and feasting. It went over so well that they repeated the festivities the following year. They’ve done the same (almost) every year since. The event, which draws about 6 million tourists every year, pours more than 7 million liters of local beer down attendees’ gullets and more than $1 billion a year into the local economy. But the Bavarian beer bash has had a few hiccups along the way.

Especially troubled years included:

1854: Organizers were forced to cancel Oktoberfest in the face of cholera outbreaks that killed thousands in Munich and ravaged other cities across Europe. Another wave of the waterborne illness preempted the festival in 1873.

1866: Canceled due to war (Austro-Prussian).

1870: Canceled due to war (Franco-Prussian).

1914 to 1918: Canceled due to war (World War I).

1923 and 1924: Hyperinflation squelched the festivities for two consecutive years when, per PBS, “the exchange rate… was one trillion Marks to one dollar, and a wheelbarrow full of money would not even buy a newspaper.”

1939 to 1945: Canceled due to war (World War II).

1980: A neo-Nazi extremist detonated a hand grenade packed with nails in the midst of the celebration, killing 13 revelers and wounding more than 200 in what the New York Times called Germany’s deadliest-ever right-wing terrorist attack.

2007: Officials banned American heiress Paris Hilton from attending Oktoberfest the year after she appeared in Munich, wearing a dirndl, to promote her newly launched canned wine. Although the festival does have a wine tent, locals didn’t appreciate Hilton’s particular brand of self-promotion, which they said “cheapened” the event.

This year may belong on the list as well. The festival, which concluded earlier this month, wasn’t canceled—but its timing, alongside a massive influx of refugees arriving in Germany by train, helped prompt the country’s decision to impose emergency border controls in mid-September. As TIME explained:

Bavarian Interior Minister Joachim Herrmann… warned of a potential culture clash between crowds of drunken people from Oktoberfest and refugees from the war-torn Middle East—though it wasn’t exactly clear who would pose more of a danger to the other. “Refugees from Muslim countries may not be used to seeing extremely drunk people in public,” he said. “It might seem a bit odd to some of them.”

Read more about this year’s Oktoberfest, here on TIME.com

Read more about the history of Munich, here in the TIME archives: The Young City

Pie

The “pye”—as it used to be spelled—is a venerable dish, which can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece and Rome. But those pastry-based dishes weren’t the desserts we tend to think of today. Instead, they were overwhelmingly savory dishes. And for good reason: the crusts could help the contents of the pie (meat, typically) last a little longer than they would otherwise.

Even apple pies didn’t used to look the way they do now:

There are few things as American as apple pie, as the saying goes, but like much of America’s pie tradition, the original apple pie recipes came from England. These pre-Revolutionary prototypes were made with unsweetened apples and encased in an inedible shell. Yet the apple pie did develop a following, and was first referenced in the year 1589, in Menaphon by poet R. Greene: “Thy breath is like the steeme of apple pies.”

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Pie

Eggnog

Eggnog is centuries old, it turns out:

While culinary historians debate its exact lineage, most agree eggnog originated from the early medieval Britain “posset,” a hot, milky, ale-like drink. By the 13th century, monks were known to drink a posset with eggs and figs. Milk, eggs, and sherry were foods of the wealthy, so eggnog was often used in toasts to prosperity and good health.

But it wasn’t always associated with the end-of-year holiday season. That happened when the drink came to the Americas; even George Washington had his own signature recipe for eggnog, which by his time had begun to be made with rum.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Eggnog

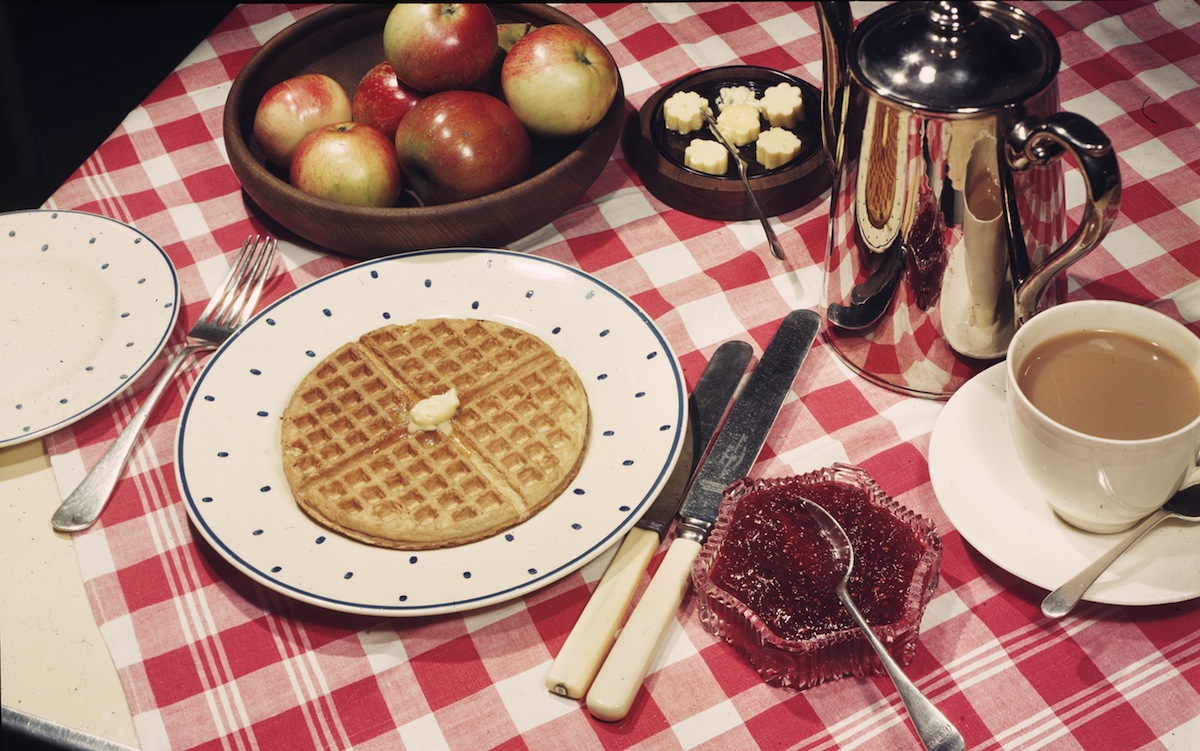

Waffles

This peculiarly patterned breakfast staple has a surprisingly long and illustrious history. The ancient Greeks used a tool kind of like a waffle iron to make cakes, and the treat came to the New World with some of its earliest European settlers:

Waffles arrived in the U.S. with the Pilgrims, who sampled them in Holland en route to Massachusetts. Thomas Jefferson reportedly brought a waffle iron home from France around 1789, helping spark a fad for waffle parties in the States.

But it wasn’t until the 1930s that a California family combined instant waffle mix, electricity and ingenuity to come up with a way to mass-produce waffles. The eventual result, if you haven’t already guessed, was Eggos.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Waffles

Peanut Butter

Peanut butter’s origins are a bit mysterious. Contrary to the popular myth that George Washington Carter came up with the idea, there’s evidence that some version of peanut butter was being made at least a couple decades before he published his 1916 text How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it For Human Consumption:

Peanut butter’s true inventor is unknown, but Dr. John Harvey Kellogg has as good a claim to the title as anyone. In 1895, the cereal pioneer patented a process for turning raw peanuts into a butter-like vegetarian health food that he fed to clients at his Battle Creek, Mich., sanatorium. The taste caught on, and in a few years, the spread had gone mainstream.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Peanut Butter

Buffalo Wings

Unlike peanut butter, Buffalo wings have a an easily identified origin: Buffalo, N.Y. But what exactly happened to spark its birth is a little blurrier:

There are at least two different versions of the Buffalo wing’s origin, although they contain the same basic facts. The first plate of wings was served in 1964 at a family-owned establishment in Buffalo called the Anchor Bar. The wings were the brainchild of Teressa Bellissimo, who covered them in her own special sauce and served them with a side of blue cheese and celery because that’s what she had available. Except for the occasional naysayer who claims to be the true inventor, these facts are reasonably undisputed. The rest of the story is anybody’s guess.

In one version of the story, the dish was invented merely to get rid of a surplus of chicken wings; in another version, Bellissimo’s son specifically asked for wings.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Buffalo Wings

Maple Syrup

The American maple-syrup industry can be traced back to the 17th century, when farmers began to tap the trees on their properties for a sweetener that was, at the time, cheaper than sugar:

Early settlers in the U.S. Northeast and Canada learned about sugar maples from Native Americans. Various legends exist to explain the initial discovery. One is that the chief of a tribe threw a tomahawk at a tree, sap ran out and his wife boiled venison in the liquid. Another version holds that Native Americans stumbled on sap running from a broken maple branch.

The old system of making maple syrup—leaving buckets under taps, collecting sap, hauling the buckets to the sugar house to be heated—was eventually widely replaced by a method that used tubes and vacuums rather than buckets and gravity.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Maple Syrup

Salt

Salt isn’t technically a food in itself, but it makes so many foods taste so much better that we couldn’t leave it off the list. Plus, its history is one of the longest, most interesting food stories out there, dating all the way back to the days when, as TIME put it in 1982, “animals wore paths to salt licks [and] men followed.” Salt was, eventually, one of the pillars of civilization:

Not only did salt serve to flavor and preserve food, it made a good antiseptic, which is why the Roman word for these salubrious crystals (sal) is a first cousin to Salus, the goddess of health. Of all the roads that led to Rome, one of the busiest was the Via Salaria, the salt route, over which Roman soldiers marched and merchants drove oxcarts full of the precious crystals up the Tiber from the salt pans at Ostia. A soldier’s pay—consisting in part of salt—came to be known as solarium argentum, from which we derive the word salary. A soldier’s salary was cut if he “was not worth his salt,” a phrase that came into being because the Greeks and Romans often bought slaves with salt.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Salt

Barbecue

Though the word “barbecue” is misapplied to all manner of grilled meats, it actually refers to a specific process (indirect heat, slow cooking) and comes from a specific tradition:

No one is really sure where the term barbecue originated. The conventional wisdom is that the Spanish, upon landing in the Caribbean, used the word barbacoa to refer to the natives’ method of slow-cooking meat over a wooden platform. By the 19th century, the culinary technique was well established in the American South, and because pigs were prevalent in the region, pork became the primary meat at barbecues.

Eventually, barbecue separated into several regional styles with their own preferences for meats and flavors.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Barbecue

Leftovers

So, you run out and make or buy all these foods, now that they’re on your mind, but there’s no way you can eat them all right away. Which brings us to leftovers. It’s not as if someone had to “invent” the idea of saving what remains at the end of a meal—after all, in the pre-modern feast-and-famine cycle, saving the fruit of the harvest was a matter of life and death. But that doesn’t mean that the look of leftovers hasn’t changed over the years. Thanks, largely, to refrigeration:

According to Dupont, which later invented the coolant Freon, ice was harvested where it formed naturally — including from New York City’s rivers — and shipped to the South, all in the name of food storage. In the 1840s, a Florida physician named John Gorrie, trying to cool the rooms where patients were suffering from yellow fever, figured out how to make ice using mechanical refrigeration, paving the way for household refrigerators that appeared in American homes en masse in the 1920s and 1930s. It wasn’t a moment too soon. As families struggled to feed their children during the Great Depression, it was unthinkable to throw away leftovers.

Read the full story here: A Brief History of Leftovers

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com