A week ago, Taliban insurgents in Afghanistan captured what was their last stronghold before they were driven from power by the U.S.-led invasion of the country in 2001. The Taliban raid on Kunduz in northern Afghanistan prompted a massive counteroffensive by Afghan and international forces. On Oct. 5, after days of bloody fighting, many sections of Kunduz were reported to be once again in the hands of the Afghan government. Although the two sides reportedly continued to clash on the outskirts, residents were said to be venturing out on to the city’s streets and some shops reopened.

But even as some calm returned to parts of Kunduz, pressure mounted on U.S. and Afghan authorities to explain the bombing of a Doctors Without Borders hospital that killed 23 people, including 13 staff and 10 patients, at the weekend.

“We do know that American air assets … were engaged in the Kunduz vicinity, and we do know that the structures that — you see in the news — were destroyed,” U.S. defense secretary Ash Carter told reporters on Oct. 4, a day after the bombing, promising a full investigation into the tragedy, which occurred as U.S. forces supported their Afghan counterparts trying to retake Kunduz from the Taliban. “I just can’t tell you what the connection is at this time.” Earlier, President Obama also offered his condolences to the victims of the bombing, which the medical charity, known by its French acronym MSF, labelled a “war crime.”

MSF, which said it is pulling out of the city following the bombing, also rejected claims by some Afghan government officials that Taliban fighters were present at the site. “These statements imply that Afghan and U.S. forces working together decided to raze to the ground a fully functioning hospital — with more than 180 staff and patients inside — because they claim that members of the Taliban were present,” the charity’s general director, Christopher Stokes, said in a statement posted on the MSF website.

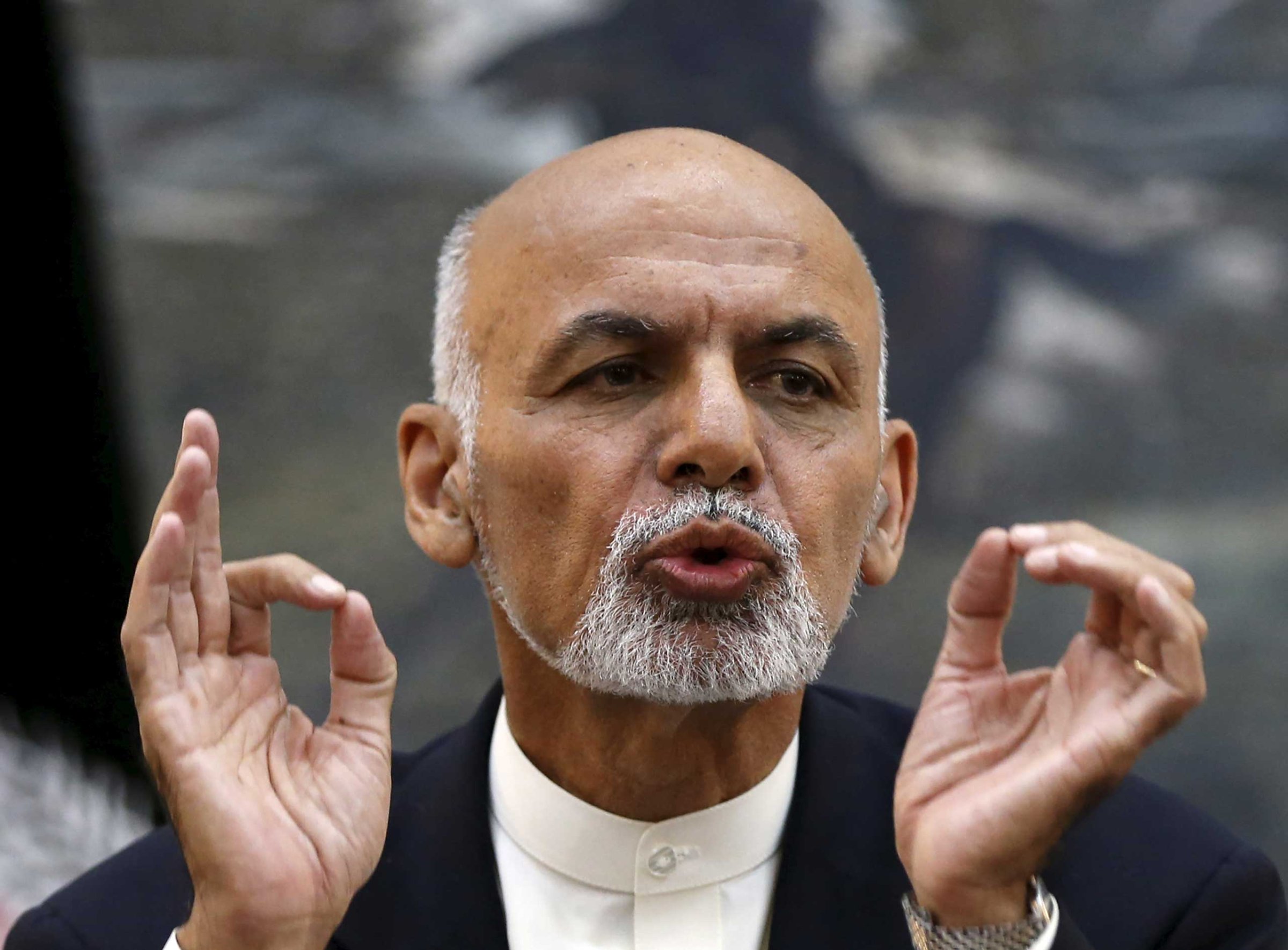

As the charity called for an independent investigation into the circumstances surrounding the bombing, Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani expressed his “deep sorrow” over the tragedy. In a statement at the weekend, he said both he and General John Campbell, the American commander who leads international forces in Afghanistan, “agreed to launch a joint and thorough investigation.”

But unlike his predecessor Hamid Karzai, Ghani stopped short of criticizing U.S. forces, saying only that both “Afghan and foreign forces alike must put in serious efforts not to target public places in military operations.” Karzai, in contrast, would respond to casualties of suspected U.S. airstrikes with forceful condemnations of foreign troops.

“From the Afghan side they can’t afford for this to be yet another reason for the Americans to leave sooner rather than later,” says Daniel Markey, a senior research professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies in Washington.

Ghani, say analysts, is treading with caution in the face of an insurgent movement that, despite internal problems, has grown in strength as the last foreign troops in the country prepare to leave. From a high of over 100,000 in 2011, there are now less than 10,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan, and a total of around 13,000 international troops. Speaking at a joint White House press conference with President Ghani earlier this year, President Obama said he aimed to reduce U.S. troop levels to a “Kabul-based embassy presence by the end of 2016.”

The Taliban’s strength was on display in Kunduz, where many expected the insurgents to retreat after a brief symbolic capture of a significant urban center. Instead, fighting continues on the outskirts after a week of bloody battles in and around Kunduz.

“I think a lot of people expected the Taliban to claim a symbolic victory of taking Kunduz and leave. But they haven’t — they’ve dug in. Unfortunately, they’ve held out much better than what anyone predicted. They did have a large number of fighters and they were well prepared,” says Kate Clark, the Kabul-based country director of the Afghanistan Analysts Network, a non-profit research organization. “They had control of a number of surrounding districts with routes in and out.”

“The taking of Kunduz was bad enough and a major mistake like [the bombing of the MSF hospital], at least in some quarters in Washington, will just be a further demonstration of the futility of this fight. And of course that’s troubling for Ghani and puts him in a difficult spot, because he has been asking for a larger and longer U.S troop presence,” says Markey.

Lacking both financial and military resources, the Afghan government recognizes that it needs international support, says Matt Waldman, an associate fellow at the London-based Chatham House think tank. “You have a government that is essentially struggling — there are deep questions about whether it can fight this war,” he says. “The [Afghan] government needs support if it is to sustain its efforts in resisting and containing the Taliban.”

Clark says Ghani’s stance also reflects the fact that “relations between the U.S. and Afghanistan under Ghani are very, very different than under Karzai.” “Karzai, in his later years, portrayed the Americans as the enemies of the Afghan people. He never really saw the war as an Afghan war — he talked about it as if it was being played out between other people. Ghani has taken much more ownership of this war, and he sees the Americans as helping him,” she explains.

“He’s already in a very different ideological position. He sees America as helping his forces,” she adds.

But Ghani’s position is not without its own risks, says Markey. “It reinforces the notion that Ghani is a tool of the Americans, that he supports outside forces who kill innocent Afghans. That narrative is already there, it was already strong, and it’s reinforced. This was a one, two punch — the taking of Kunduz and the attack on MSF, both of which serve Taliban purposes quite well.”

Ultimately, adds Markey, “there’s nothing that he can say that would be particularly helpful.” “Continued relative quiet with a goal of effectively tamping down criticism — that’s the best they can do. There’s no win in this. Until Kunduz is decisively retaken, this continues to be a bad news story, and the MSF story is horrible all around.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com