In April, Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani was preparing to fly to New Delhi for a state visit to India when his departure was delayed by several hours. The reason? A last minute meeting with the top NATO commander in the country amid a fierce battle between Afghan security forces and Taliban insurgents on the outskirts of the northern Afghan city of Kunduz. In 2001, Kunduz was the Taliban’s last stronghold during the U.S-led invasion of the country; now, the Taliban was trying to retake the northern Afghan city.

On Sept. 28, the insurgents finally got their prize, capturing the provincial capital of Kunduz province with a raid launched in early hours of Monday morning. By the afternoon, the Taliban’s distinctive white banner was said to be flying in different parts of the city. As Afghan security forces retreated to the outskirts, insurgent fighters drove around Kunduz in government military vehicles, according to a resident who spoke to Afghanistan’s TOLOnews television station. Others posted triumphant victory selfies and videos on social media. In one, a group of Taliban insurgents stand in the city center, their white flag aloft; another shows a green police pick-up now apparently in the hands of the insurgents.

The fall of Kunduz came on the eve of the anniversary of the establishment of the national unity government, headed by Ghani, that has been running the country since last year. On Sept. 29, as Afghan forces launched a counter-offensive in a bid to retake the city, he called on his fellow citizens to trust the country’s troops. “The enemy has sustained heavy casualties,” he said in a nationally televised address, vowing to regain control of the city.

“The Taliban had been trying hard to capture key provincial districts and even key cities, to demonstrate their increased influence, in light of the withdrawal of NATO forces from Afghanistan,” M. Ashraf Haidari, the director general of policy & strategy at Afghanistan’s foreign ministry in Kabul, told TIME, adding: “Although the Taliban has now temporarily captured Kunduz city, we have begun deploying reinforcements, along with NATO air support, to recapture the city, while ensuring the protection of all civilians.”

But even as reinforcements make their way to Kunduz, backed up by U.S. airstrikes, the Taliban’s advance raises troubling questions about the state of Afghanistan’s security apparatus as the last remaining foreign troops prepare to depart the country. NATO’s combat mission in Afghanistan ended in December 2014, leaving behind a residual force of some 13,000 troops—including just under 10,000 U.S. soldiers—focused on training local forces.

“No matter how you slice it, this is a huge defeat for the Afghan security forces,” says Michael Kugelman, a senior analyst at the Wilson Center in Washington. “This offensive and this takeover of Kunduz didn’t come out of nowhere.”

The Taliban has been eyeing the city for months, says Kugelman, so the city’s capture by the insurgents suggests “an inability or unwillingness” on the part of the Afghan forces to “confront this threat ahead of time.”

Reports from Afghanistan highlight the lack of preparedness despite mounting warnings, with Dawlat Waziri, the deputy spokesman for Afghanistan’s defense ministry, telling TOLOnews that “no collapse would have happened if there was full coordination in tactical areas. The problems in this aspect and the enemy has used this in its favor.”

“You also really need to single out the [Afghan] government for a lack of a vision and a lack of a plan,” says Kugelman. The Ghani administration is a year old, he notes, but the government has failed to get its nominee for the crucial post of defense minister approved by Parliament. Legislators rejected the nomination of Massoum Stanekzai, currently the country’s acting defense minister, over the summer. The incomplete cabinet has resulted in a lack of leadership, argues Kugelman.

Inside the Taliban, meanwhile, the capture of Kunduz could boost the position of Mullah Akhtar Mansour, who emerged as the insurgent group’s new leader over the summer following confirmation of the death of long-time Taliban chief Mullah Omar. The announcement was accompanied by speculation about the potential for dissent with the Taliban ranks, as different factions staked their claim to lead the insurgency in Afghanistan.

But the capture of Kunduz “amplifies the fact that despite its fractures and vulnerabilities and leadership crisis, the Taliban remains a very potent fighting force,” says Kugelman.

At the time, confirmation of Omar’s death, and the prospect of a drawn-out leadership battle in the upper ranks of the Taliban, also appeared to be a win for the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS). ISIS had already signaled it’s intention to expand into war-torn Afghanistan—and the Taliban leadership crisis seemed to present an opportunity for the group to recruit disaffected Taliban commanders and foot-soldiers. The Taliban’s capture of Kunduz could have the opposite effect.

With Afghan forces and U.S. warplanes launching a massive counteroffensive, it remains unclear how long the insurgent group might be able to hold on to its prize. But the Taliban, which has been ramping up violent attacks in Afghanistan since before NATO ended its combat mission, may have already scored a symbolic goal. “At the end of the day, Kunduz shows that the Taliban rules the roost when it comes to being the top militant faction in the country,” says Kugelman.

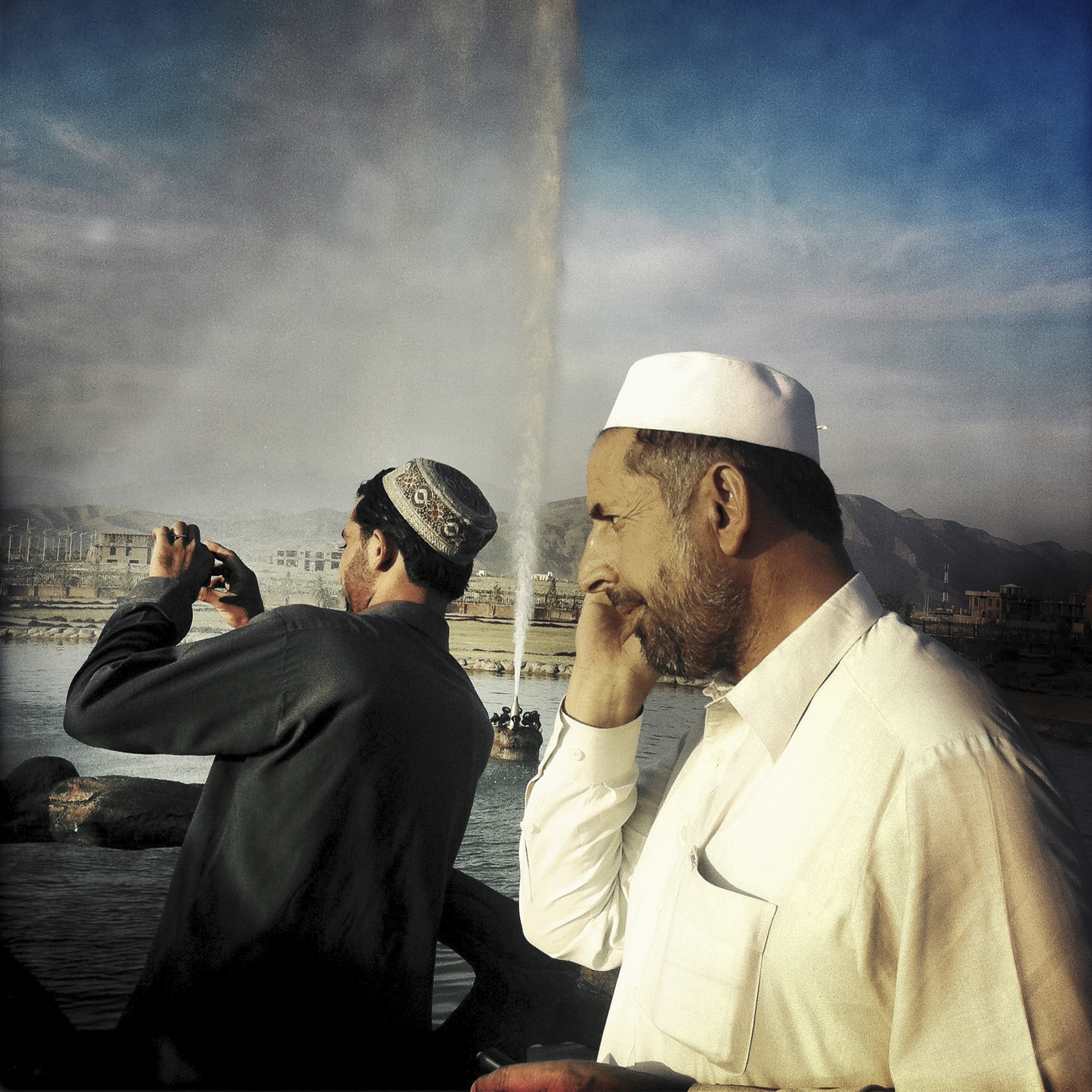

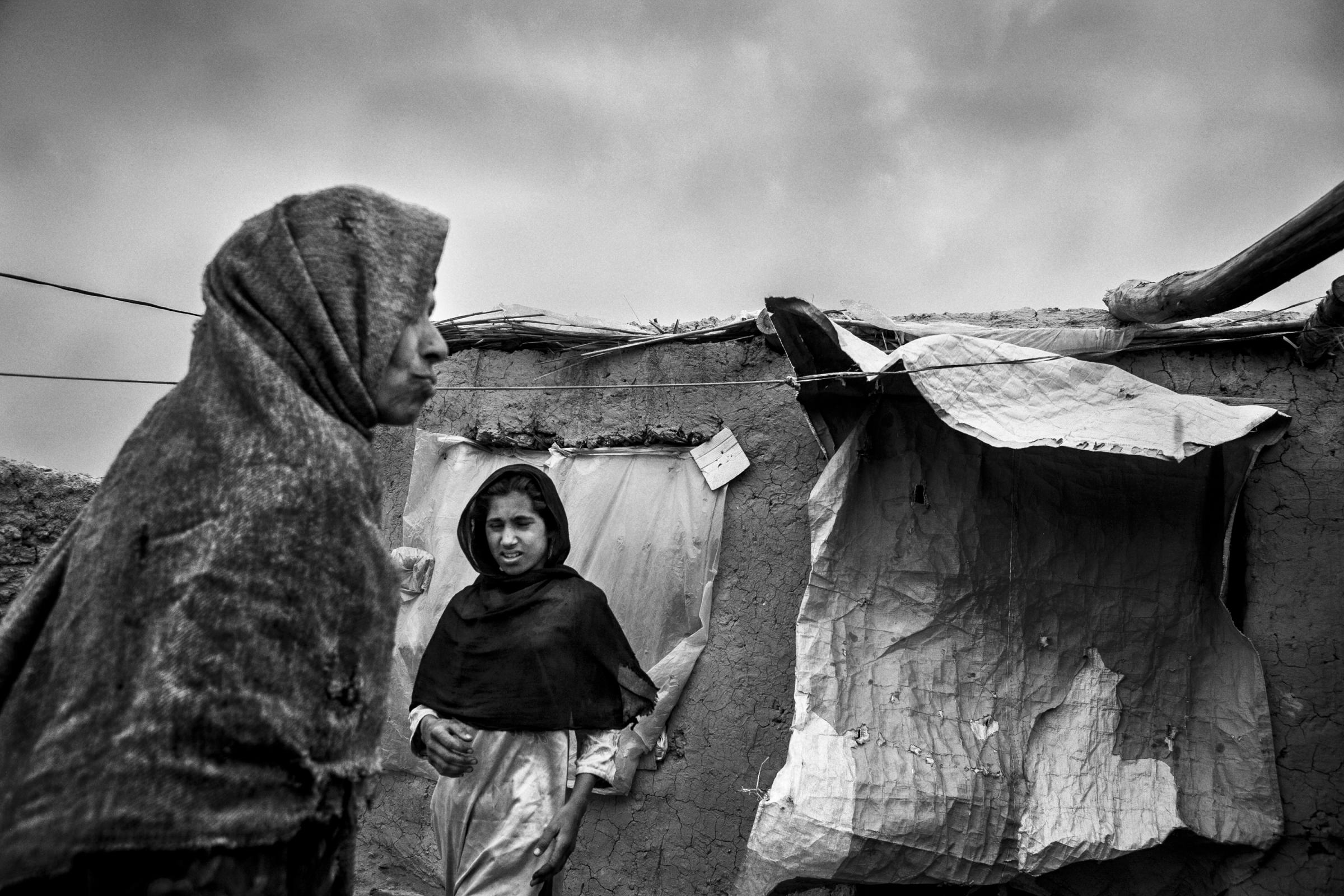

See Everyday Life in Afghanistan

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com