The new movie The Martian, the story of an ill-fated NASA mission to Mars, takes place in the relatively near future. While some of the science has been nit-picked—though relatively little, considering it’s a movie—one aspect is, historically speaking, completely believable: the idea that human beings would be sending manned missions to the Red Planet is the very near future.

As NASA revealed that scientists have found evidence of water on Mars on Monday, our solar system neighbor became the focus of renewed interest—but it’s been decades since humankind first heard that a Mars mission was imminent.

It started in the mid-1960s, even before the moon landing, as the fifth-ever class of astronauts chosen by NASA were told that a Mars mission could possibly be in their future. By 1969, with the lunar landing a success, they had a timeline: engineer Wernher von Braun said the American space program could get there by 1982, while the more cautious Vice President Spiro Agnew was aiming for the year 2000 at the latest.

MORE: A Brief History of the Search for Water on Mars

A panel headed by Agnew was, later that year, settled on a middle ground: “If Congress compromises on a maximum NASA budget of $7.65 billion by 1980,” TIME reported, “the Martian touchdown can be achieved in 1986.” Over the next few years, the 1986 deadline continued to be discussed. (Attention, Hollywood: By 1972, NASA even got into the weeds with the question of what to do about the astronauts’ inevitable romantic entanglements during a 590-day mission.)

Fast-forward to the mid-1980s. Humankind was not on Mars.

But that didn’t mean we weren’t still trying. By 1985, the idea of a joint U.S.-Soviet mission was floated by space experts from around the world. It was to be a Cold War-defying act of scientific greatness, made possible by splitting the bill. The deadline that time around: 2010.

Hopes of that idea becoming reality were temporarily dashed the following year by the Challenger space shuttle disaster, which led NASA to recalibrate its entire mission, but by 1988 it was back on track. “A manned trip to Mars, long the stuff of science fiction, now appears to be just a matter of time. The mystic planet, glowing red and ever brighter in the night skies, is heading toward its closest approach to the earth in 17 years this September, tantalizingly near and beckoning,” TIME noted in a cover story about the progress the U.S. and the USSR were both making in research and preparation for such a trip.

MORE: What the Modern Presence of Water on Mars Means

By the start of the ’90s, President George H. W. Bush had adjusted the target to aim for “astronauts on the red sands of Mars by 2019,” per TIME. Science experts like TIME’s Michael Lemonick agreed that 2020 was a “reasonable” estimate for when we’d get there. But, as the next decade progressed, there was more and more news of probes and rovers going to Mars, and less and less news of potential manned missions. At the dawn of a new century that trend continued.

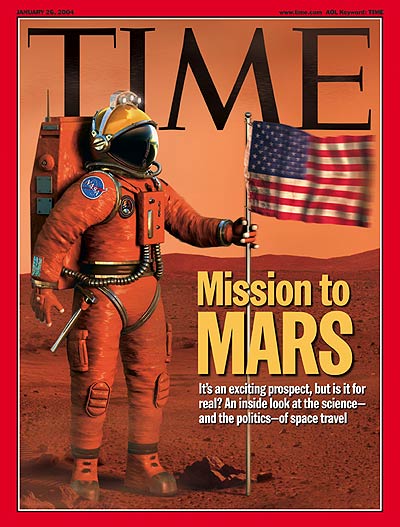

Then, however, George W. Bush announced that Mars was once again a priority for NASA. The summer before the 2004 election, he laid out a plan for returning to the moon around 2015 and getting to Mars not too long after. “[Though] the year 2030 was bandied about in the press as a target for putting a man on Mars, the President was careful not to set a date,” TIME’s Jeffrey Kluger noted. Some experts at the time even saw 2030 as unnecessarily far away; with real dedication to the mission, they estimated, the 2010 date could have been met.

And now 2010 has come and gone, and 2030 is practically just around the corner. But we haven’t given up: just about a month ago, none other than Buzz Aldrin declared that he wanted to see humans on Mars by 2039.

So The Martian may yet become even more scientifically accurate than its creators could have planned, something that future astronauts may well find worth raising a glass (of Martian water) to celebrate.

Read TIME’s Jeffrey Kluger on The Martian: The Martian Celebrates the Gutsy Ambition That We’ve Denied the Real NASA

Read a 1972 imagining of a mission to Mars, here in the TIME Vault: 1986: A Space Odyssey to Mars

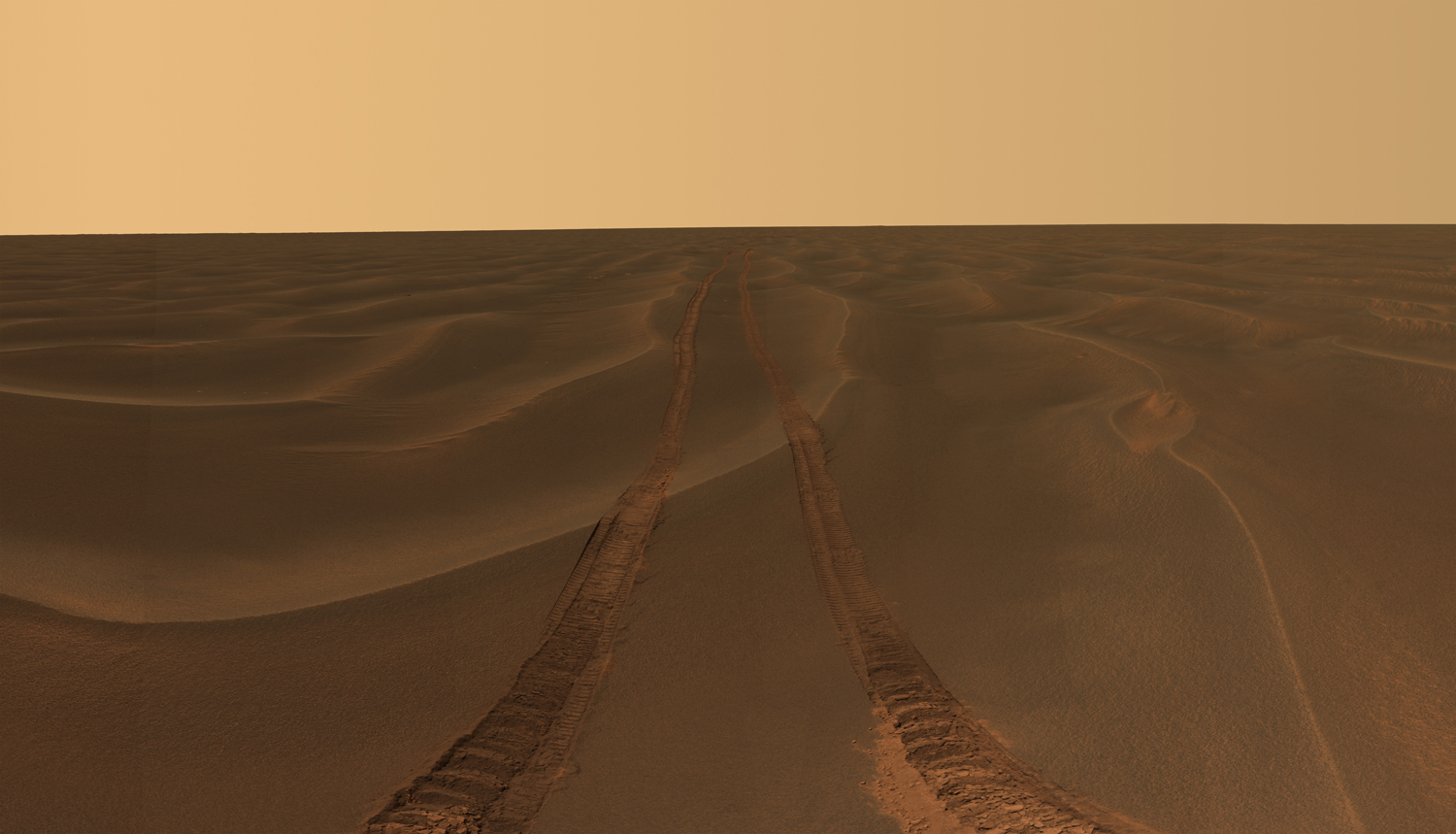

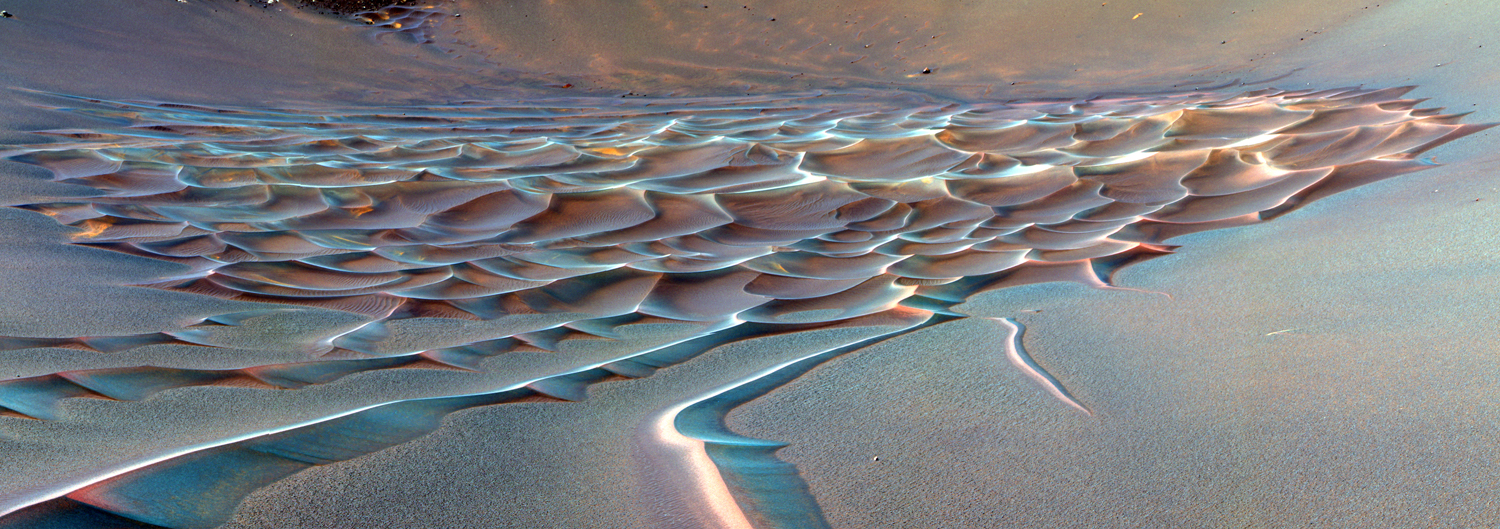

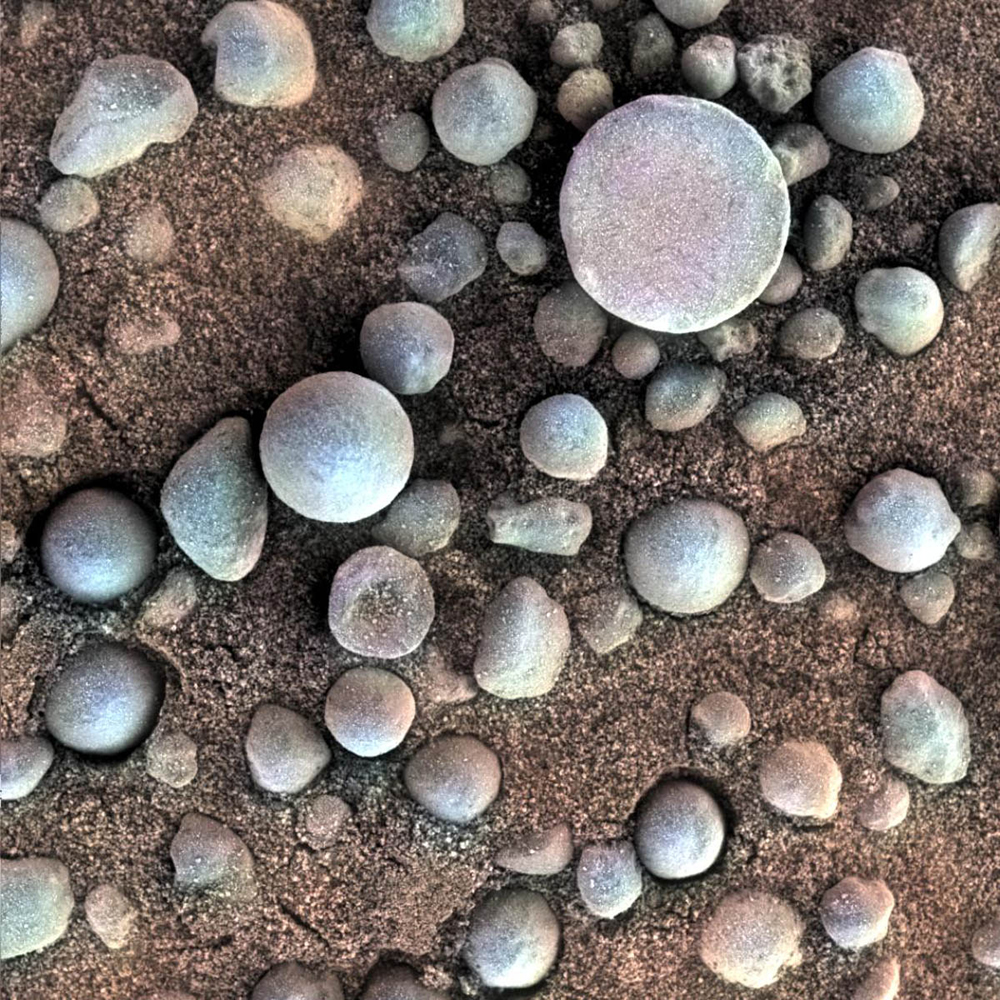

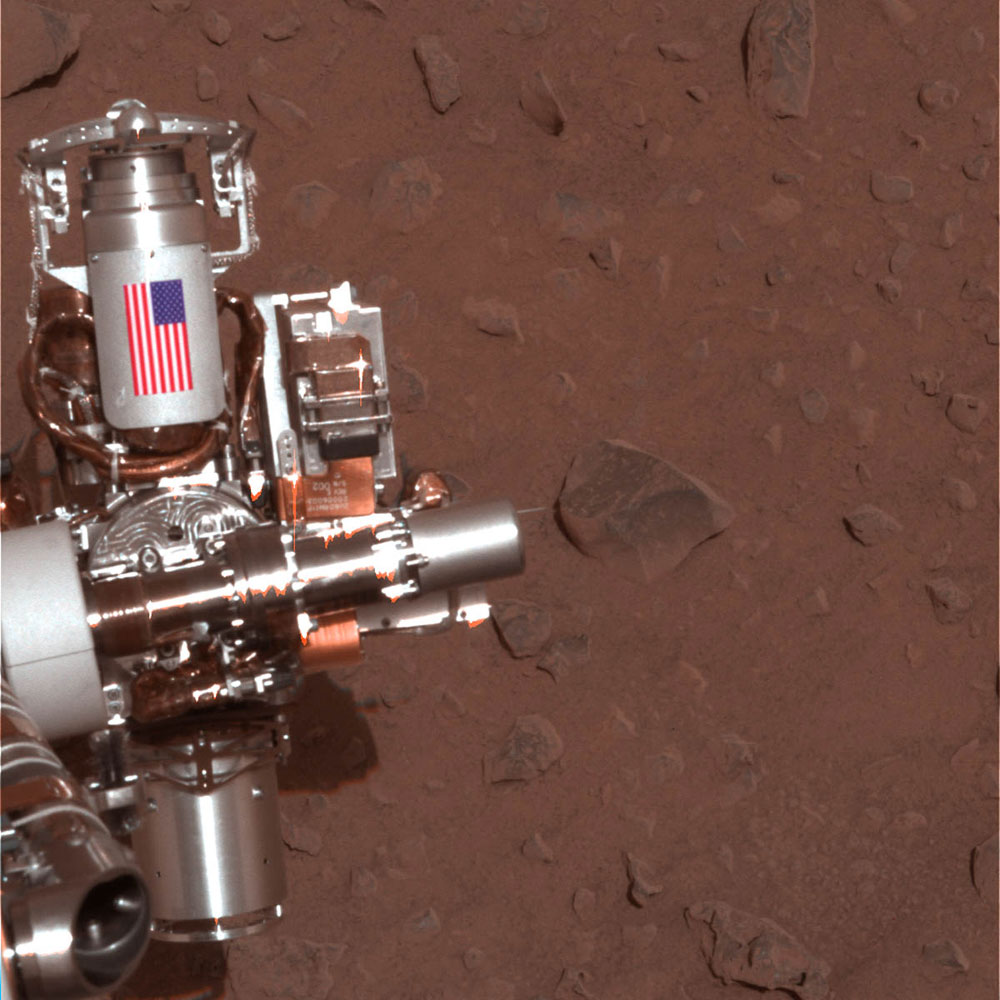

PHOTOS: The Most Beautiful Panoramas and Mosaics From Opportunity’s Decade on Mars

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com