This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

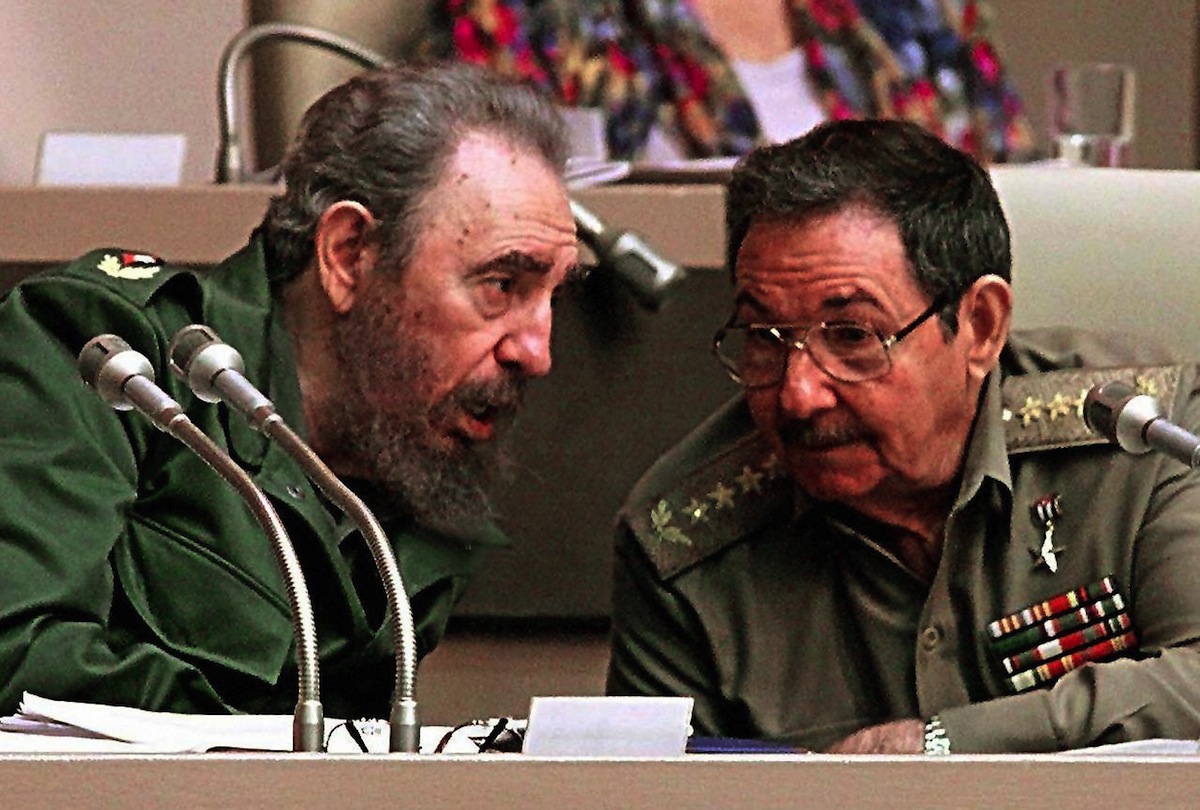

The restoration of U.S. and Cuban diplomatic ties is quite an event, particularly given the hostility that defined relations between the two countries for so long. President Obama’s decision to re-open an embassy in Havana and Raul Castro’s agreement to do the same in Washington continues the thaw in U.S.-Cuban relations. The steps taken by both countries have generated much publicity over the past few months. Numerous U.S. media outlets have produced stories on the implications for Obama’s legacy and the potential fallout for 2016 presidential candidates. As usual Washington politicians and pundits have focused their attention on the reasons for the U.S. shift. Yet, it is not President Obama’s decision to seek a normalization that warrants the most attention, but rather the Castro government’s reasoning behind their determination to chart a new course in U.S.-Cuban relations. In fact, much more can be learned from concentrating instead on what is behind the Cuban leadership’s thinking.

Havana’s recent decisions are deeply rooted in what can best be termed as Cuba’s “revolutionary pragmatism.” Though the Castro government continually speaks the language of revolutionary change, it also has also taken a sensible view to foreign policy matters when necessary. Such an approach has guided Cuban engagement with the world from the 1960s to the present.

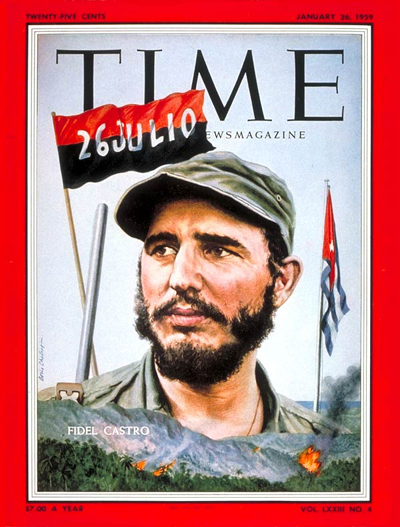

“Revolutionary pragmatism” traces back to the very beginning of the Castro regime. In the years immediately following the Cuban Revolution, for example, a top issue in US-Cuban relations included Fidel Castro’s support for anti-US guerilla movements throughout Latin America. Castro repeatedly challenged Latin Americans and others around the world to stand up to the United States. He famously declared in 1962 that it was “the duty of every revolutionary to make the revolution. In America and the world, it is known that the revolution will be victorious, but it is improper revolutionary behavior to sit at one’s doorstep waiting for the corpse of imperialism to pass by.”

Yet, privately, Castro proved willing to develop a foreign policy based on practical considerations. On a recent research trip to Cuba I gained access to the Foreign Ministry Archive in Havana and was surprised at what I found. Many detailed reports from the early 1960s discussed the prospects for revolution in Central and South America, but concluded that conditions were not ripe in many nations for radical change. This reality led to a more pragmatic position being taken by leaders in Havana as they approached Latin America.

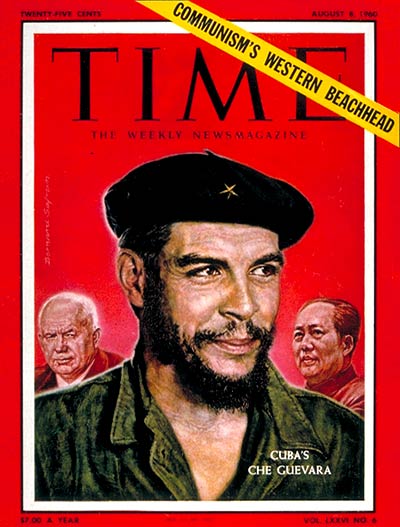

The most documented aid came in the form of training young Latin Americans in guerilla tactics who traveled to Cuba. As historian Piero Gliejeses’s excellent studies demonstrate, Castro turned his attention to Africa as early as 1964. Havana’s decision to abandon any large-scale support for revolutionary groups in Latin America was not made due to a lack of enthusiasm for challenging Washington’s traditional sphere of influence, but owed instead to practical considerations.

Similarly, in the 1980s when the Sandinista triumph in Nicaragua offered Havana an ally in Latin America, Castro held to “revolutionary pragmatism.” He counseled Daniel Ortega not to antagonize elite economic interests too much. On a visit to Managua, Castro even declared that allowing some capitalism in the Nicaraguan economy did not violate revolutionary principles. He bluntly told Nicaraguan leaders that they did not have to follow the path taken by Cuba, “Each revolution is different from the others.”

Perhaps the greatest illustration of Cuban flexibility was the Castro regime’s response to the collapse of the Soviet Union. In June 1990, after receiving word that aid from Moscow would no longer flow to Havana, Fidel Castro announced a national emergency. He called his initiative “the Special Period in Peacetime.” Cuba welcomed foreign investment, tourism, the U.S. dollar, and allowed small-scale private businesses. While many prognosticators predicated a complete collapse of the Castro regime, the revolutionary government endured due to its ability to adapt.

Thus, recent developments must be viewed within their proper historical context. As it has in the past, Castro’s regime is pursuing “revolutionary pragmatism.”

The impetus for changes in Cuba’s approach owes to several reasons. First, since the death of Hugo Chávez in 2013 Venezuela has become a questionable economic ally. Political instability coupled with a crumbling economy has likely caused Havana to view a key economic patron in Caracas as increasingly unreliable. A complete breakdown of order in Venezuela would greatly affect the Cuban economy in a negative way. Thus, a better economic relationship with the United States is one way of protecting the island from a changing relationship with Venezuela.

Other reasons for Cuba’s rapprochement with the United States owe to domestic concerns. Since taking power in 2008, Raul Castro has been open to reforms in an attempt to make socialism work for the twenty-first century. Over the last few years the Cuban government has relaxed controls over certain sectors of the economy, but reforms have been slow and halting. Anyone who has spent time in Havana cannot help but notice the aging infrastructure and inefficient public transportation system. A key to any reform agenda is attracting foreign investment, and the United States stands as an attractive partner.

Furthermore, as Raul is poised to step down from power in 2018, Cuba is starting to make preparations for a successful turnover. An improving relationship with Washington may help his likely successor, Miguel Díaz-Canel, better navigate the transfer. In sum, at this point and time, normalization of U.S.-Cuban relations serves Havana’s best interests.

It remains to be seen just how far the Cuban government will go regarding changes in policy. Going back to 2010, Raul Castro declared during a national address that “we reform, or we sink.” His recent push for renewed relations with the United States will likely create an influx of U.S. tourists and more capital from American businesses. In turn, this could place Cuba down the path of other communist nations who embraced elements of capitalism, China and Vietnam notably. Just how far Raul will go with his reform agenda remains to be seen.

Ultimately, a U.S.-Cuban thaw is a positive step. Antagonism between the two countries serves no one, especially the Cuban people. Yet, we should not see the recent shifts as merely Washington changing course. The steps taken by Havana are equally important and should be viewed as part of a long history of shrewd diplomacy. While Cuban foreign policy has traditionally been revolutionary in rhetoric, it has proven once again to be pragmatic in practice.

Matt Jacobs received his PhD in History from Ohio University in 2015. This fall he will be a Visiting Assistant Professor of Intelligence Studies and Global Affairs at Embry-Riddle’s College of Security and Intelligence. He has conducted research at the Cuban National Archive and the Cuban Foreign Ministry Archive, both in Havana.

Read more: Why Did the U.S. and Cuba Sever Diplomatic Ties in the First Place?

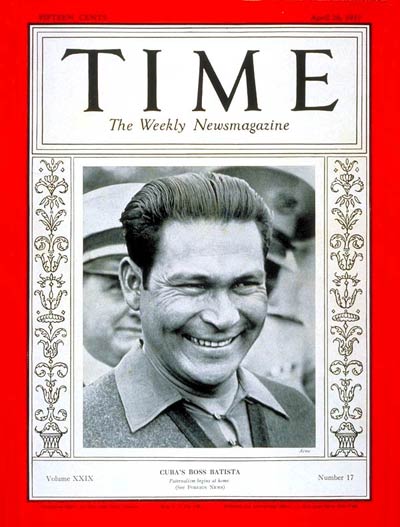

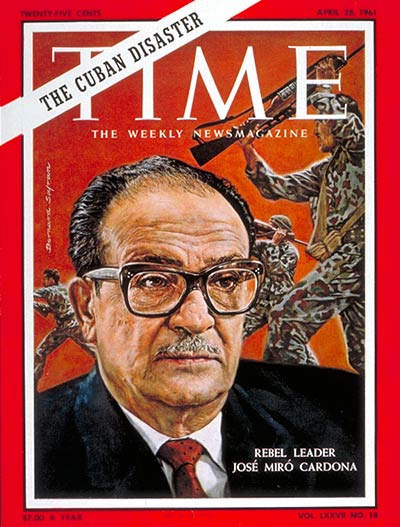

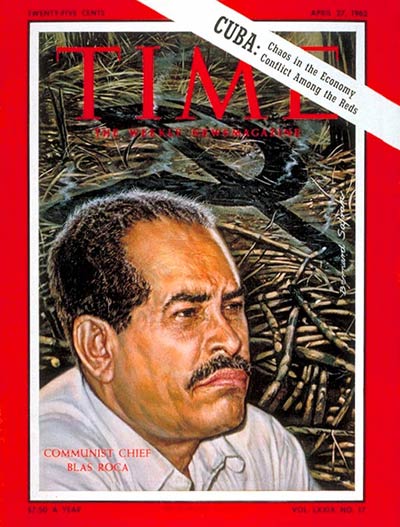

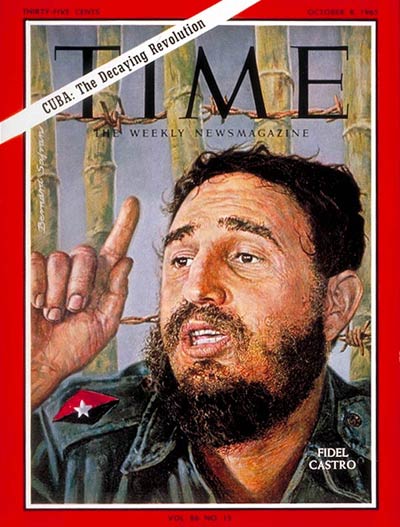

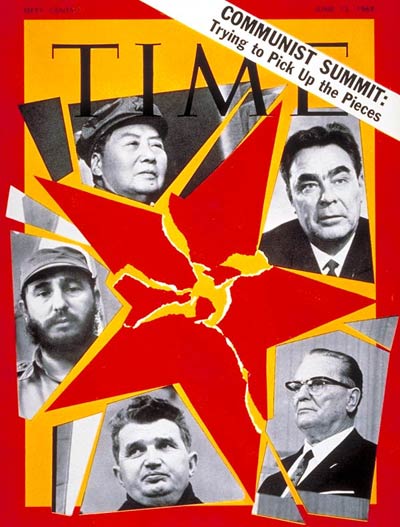

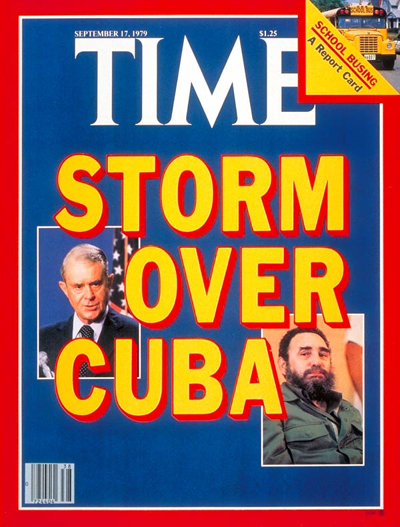

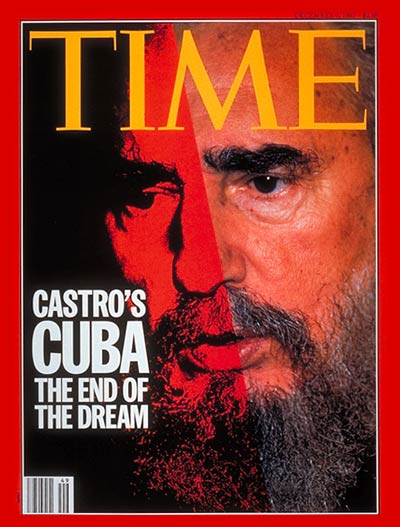

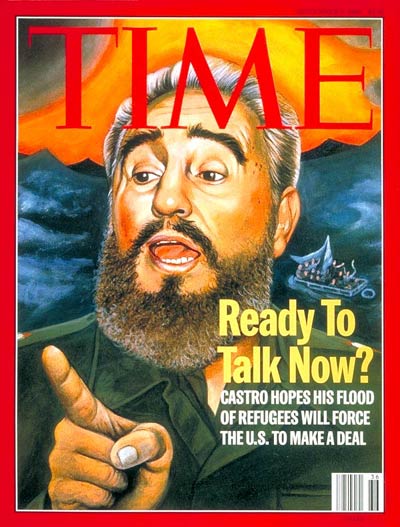

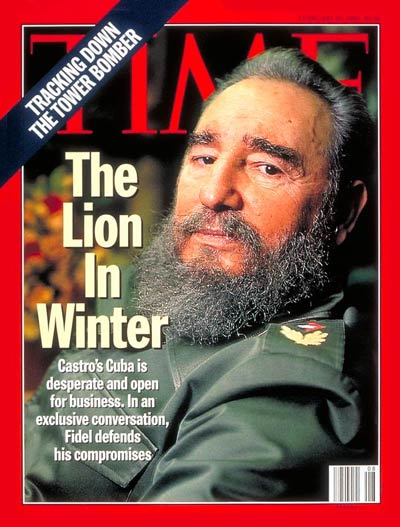

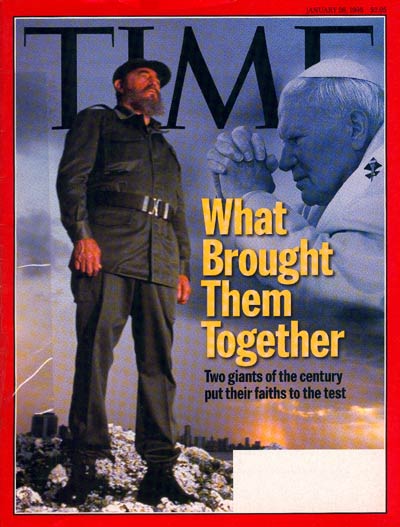

A History of Cuba-U.S. Relations in 13 TIME Covers

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com