On Wednesday, U.S. President Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro announced that the two nations are on their way to restoring diplomatic relations. Obama, speaking of the change, said that the two nations are not served by a policy rooted in events that took place a half century ago.

But what exactly did happen back then?

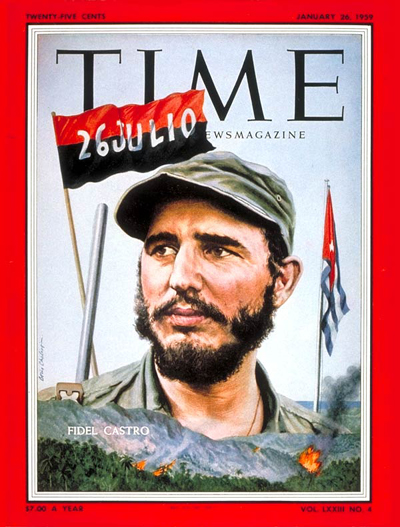

It was actually over half a century ago that Fidel Castro led Cuban rebels against Cuba’s strongman leader Fulgencio Batista, if you count from when Castro led revolutionaries to the island in late 1956. (He had been involved in anti-Batista efforts for several years before that, too.) Though early reports on the movement speak of Castro and his supporters as underdogs with no hope of victory, as 1959 dawned, they proved victorious. America watched with interest, but it wasn’t long before it became clear that Castro’s Cuba would not be an easygoing neighbor to the United States.

As Castro purged Cuba of Batista supporters, he declined to institute the democratic reforms that many had hoped for. Initially, the revolution had not been overtly Communist, but Castro moved further toward that ideology as his rule went on. In the middle of 1959, he instituted wealth-distribution and land-confiscation programs; that July, TIME reported that a former Cuban official had said that “Cuba’s No. 1 Communist… is Fidel himself.”

In a Cold War world, the rise of Communism in a nation so close to Florida was not taken lightly. Though the U.S. ambassador to Cuba, Philip W. Bonsal, did finally manage to meet with Castro that September, their discussions — partly concerned with arrests of U.S. citizens in Cuba and the government confiscation of some U.S. investments in Cuba — proved fruitless.

In the United Nations, Cuba began to stand with Communist nations against the U.S.; in Cuba, the ruling regime encouraged anti-U.S. sentiments; in early 1960, the U.S.S.R. instituted a trade-and-aid deal with Cuba; U.S. sugar producers pushed for the nation to stop buying sugar from Cuba; Castro accused the U.S. of sabotaging a ship that blew up in Havana’s harbor. The details of changes in Cuba and the U.S. reaction to those developments are complicated and often conflicting, but suffice it to say that TIME called that period a “rapidly deteriorating situation that sees Cuban-American relations reach a new low each day.”

Eventually, in late October of 1960, the U.S. imposed a strict embargo barring two-thirds of American imports from Cuba, which before then had been buying a whopping 70% of its imports from the United States. As the two nations sparred over economics, Ambassador Bonsal was recalled from Cuba, after which point both embassies — Cuba’s in D.C. and America’s in Havana — were left to be headed by chargés, which meant, TIME pointed out, that “diplomacy between the two nations will become as difficult as commerce.”

In the weeks that followed, as rumors of a possible invasion by the U.S. spread throughout Cuba, people began to line up at the U.S. embassy seeking visas to leave the island. The daily lines became an embarrassment to the Castro regime but the rumors only increased as time went on. When Castro later demanded that the two countries have the exact same number of staffers in their respective embassies (11), the U.S. brought its entire staff home instead.

The crowds were still waiting when, early in January of 1961, the embassy closed its doors; there were more than 50,000 visa applications on file at the time. As TIME reported:

The crowd of desperate Cubans swarming around the U.S. embassy in Havana refused to believe that the doors were locked and that no more visas could be issued. One man hammered on the glass, waving his U.S. Army discharge papers. A woman with a broken leg was held up piteously to the scurrying U.S. staff workers inside. “But you are the humane people! You are the humane people!” a woman pleaded, grabbing a U.S. consular official as government photographers stood near snapping pictures of those who wanted to flee Castro’s Cuba.

The U.S. could not help them—at the moment. After two years of harassment. President Eisenhower ordered the State Department to break all diplomatic ties, at both the embassy and consular level, for the first time in the history of U.S.-Latin American relations. To most Americans the wonder was that the U.S. had stood it so long.

The only place in Cuba where a U.S. presence remained would be the naval base at Guantanamo Bay; a few weeks later, the U.S. announced a decision to all end travel to Cuba. Early 1961 proved to be the end of one phase of U.S.-Cuba relations, and the beginning of another, more openly combative, phase — and this week may well mark the beginning of the next.

Read TIME’s 1959 cover story about Fidel Castro’s rebellion, here in the TIME Vault: Fidel Castro

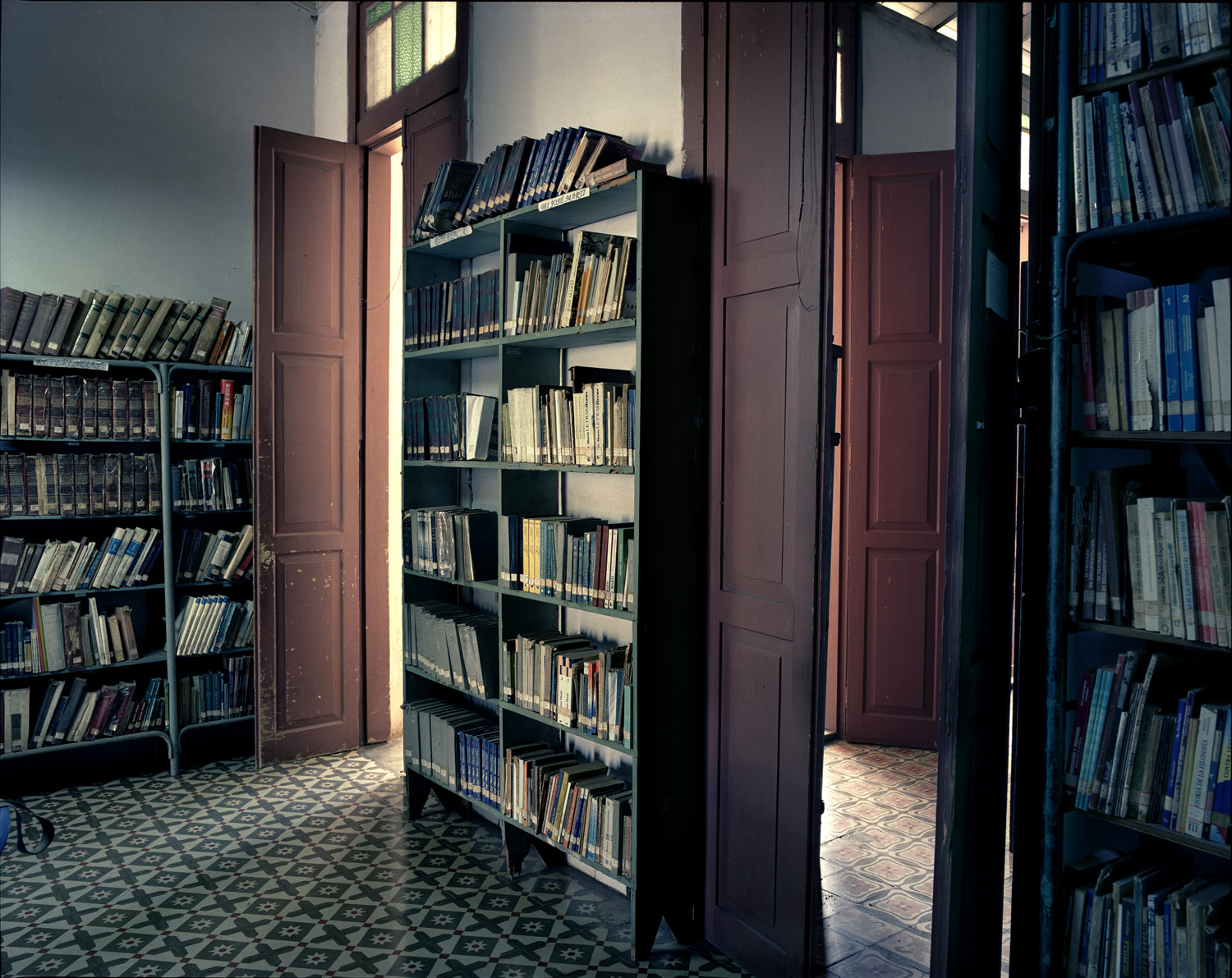

Witness Cuba's Evolution in 39 Photos

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com