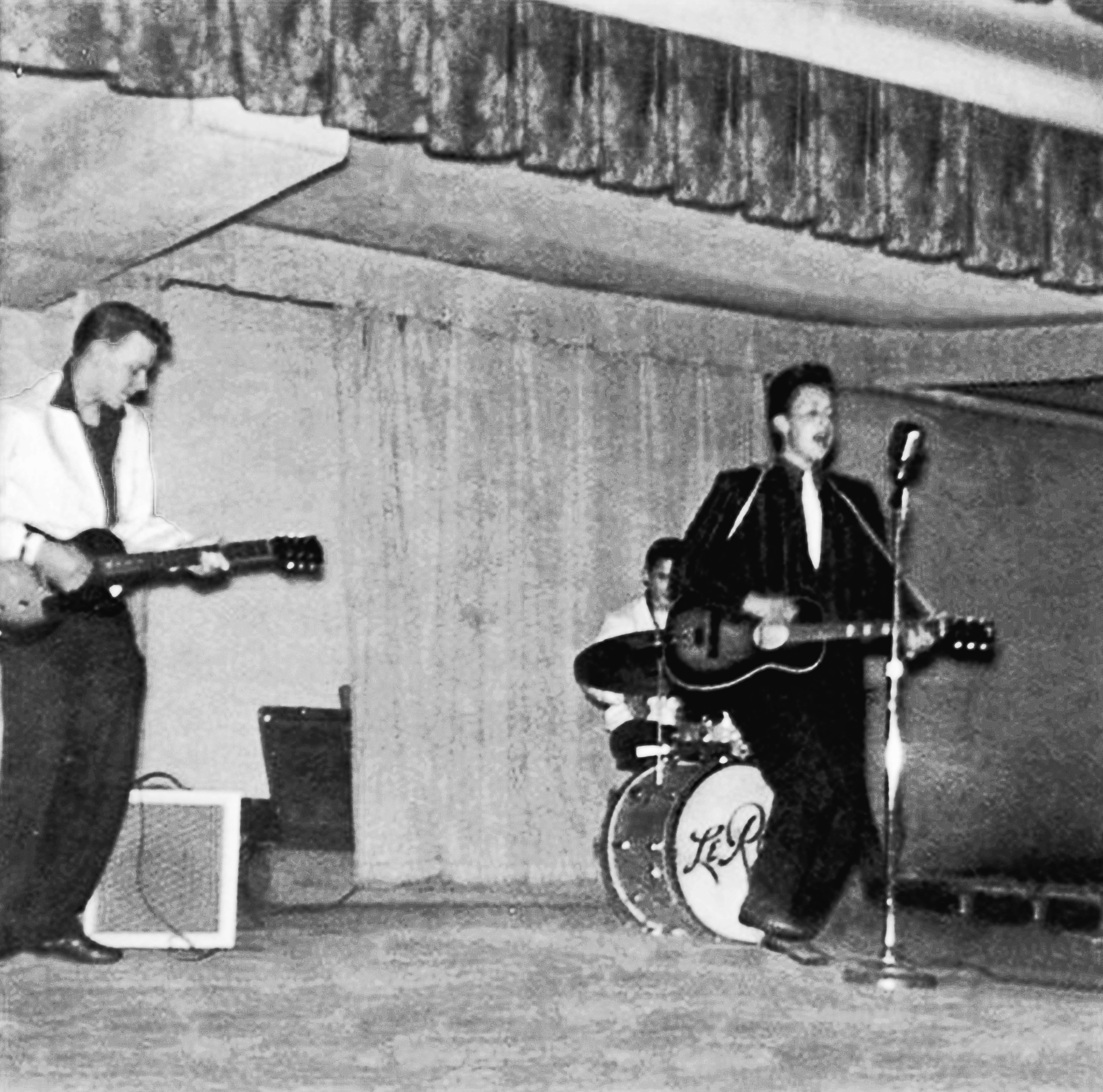

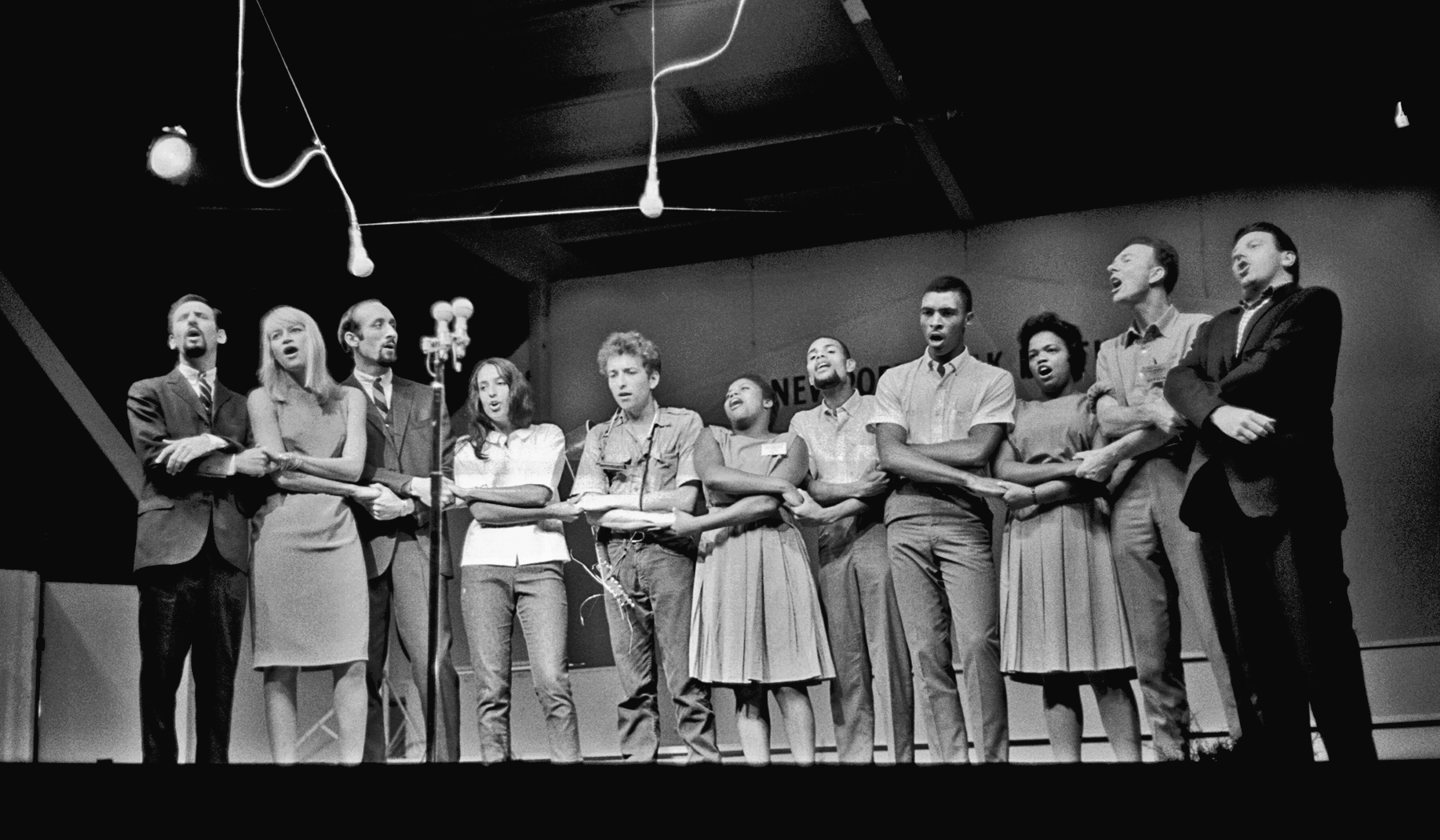

On the evening of July 25, 1965, Bob Dylan took the stage at the Newport Folk Festival in black jeans, black boots, and a black leather jacket, carrying a Fender Stratocaster in place of his familiar acoustic guitar. The crowd shifted restlessly as he tested his tuning and was joined by a quintet of backing musicians. Then the band crashed into a raw Chicago boogie and, straining to be heard over the loudest music ever to hit Newport, he snarled his opening line: “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more!”

What happened next is obscured by a maelstrom of conflicting impressions: The New York Times reported that Dylan “was roundly booed by folk-song purists, who considered this innovation the worst sort of heresy.” In some stories Pete Seeger, the gentle giant of the folk scene, tried to cut the sound cables with an axe. Some people were dancing, some were crying, many were dismayed and angry, many were cheering, many were overwhelmed by the ferocious shock of the music or astounded by the negative reactions.

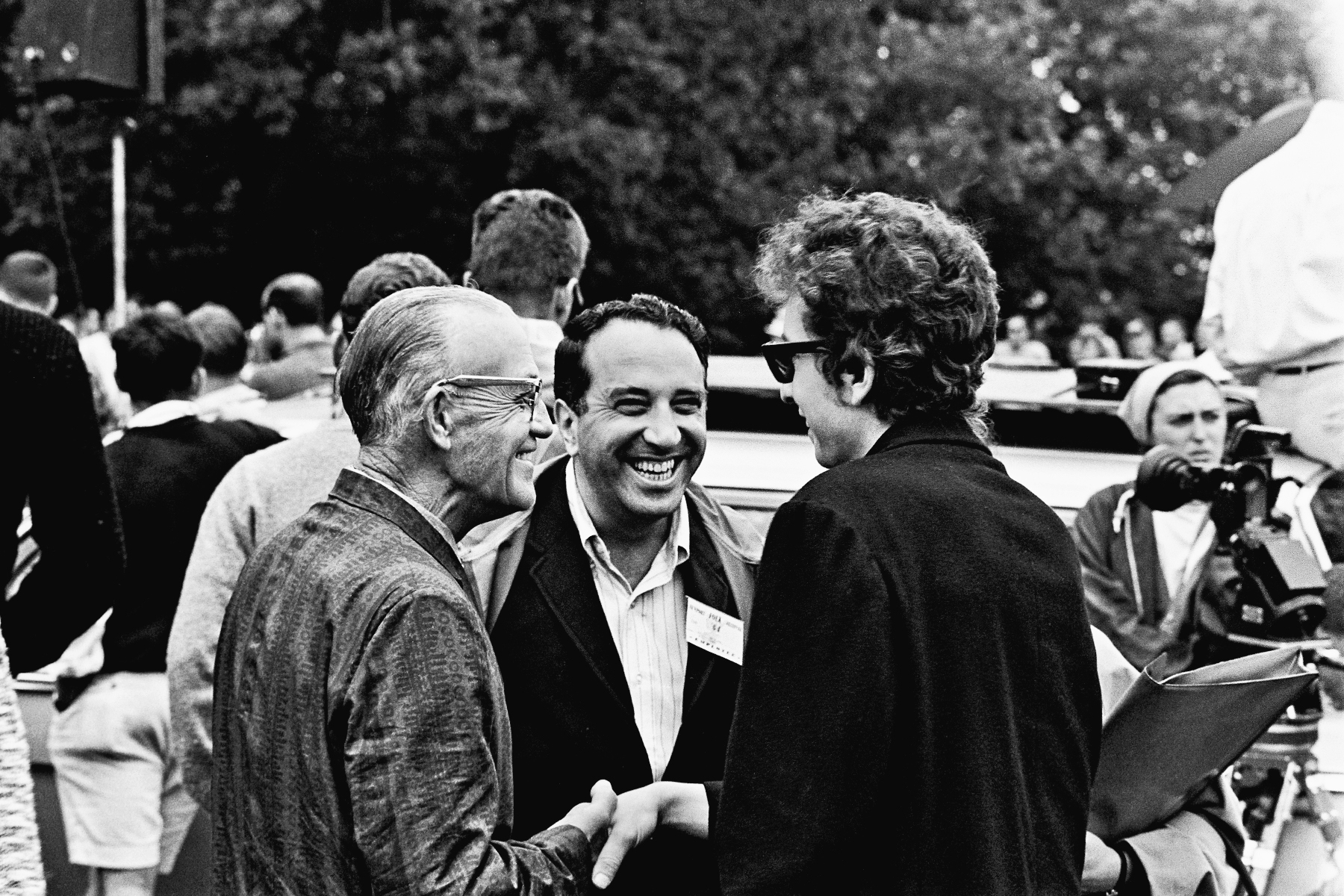

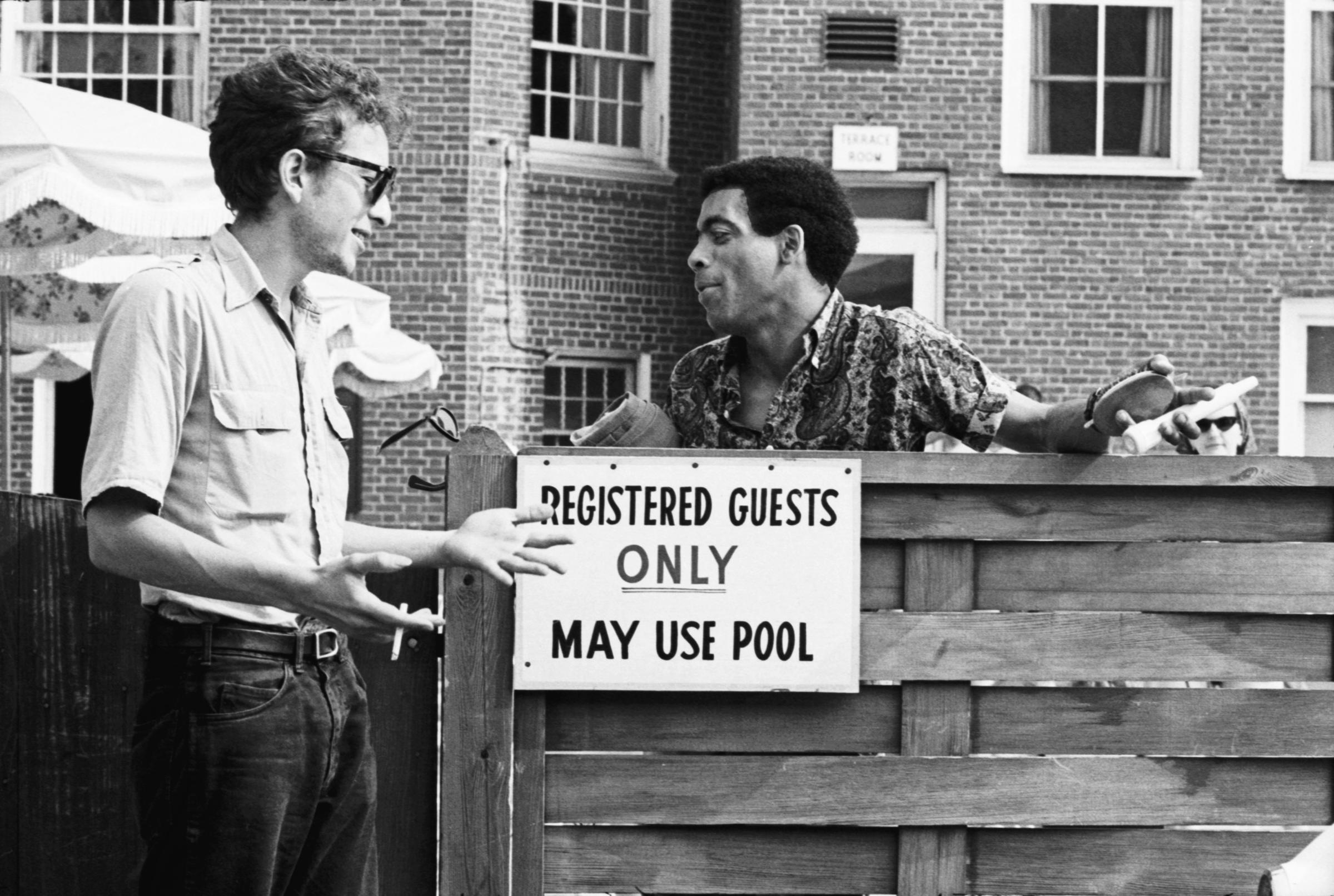

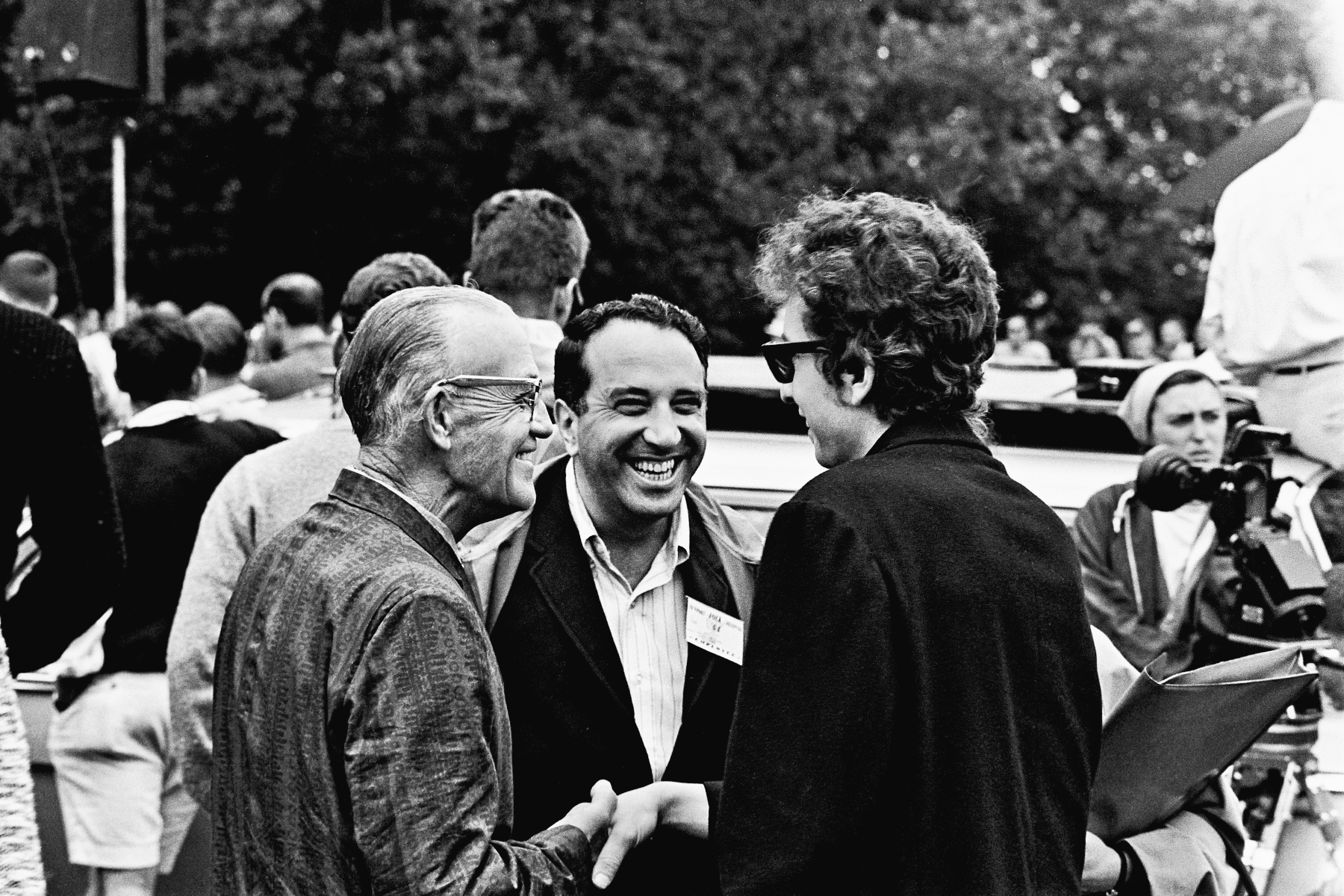

Bob Dylan TKTK

As if challenging the doubters, Dylan roared into “Like a Rolling Stone,” his new radio hit, each chorus confronting them with the question: “How does it feel?” The audience roared back its mixed feelings, and after only three songs he left the stage. The crowd was screaming louder than ever—some with anger at Dylan’s betrayal, thousands more because they had come to see their idol and he had barely performed. Peter Yarrow, of Peter, Paul, and Mary, tried to quiet them, but it was impossible. Finally, Dylan reappeared with a borrowed acoustic guitar and bid Newport a stark farewell: “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue….”

Dylan at Newport is remembered as a pioneering artist defying the rules and damn the consequences. Supporters of new musical trends ever since—punk, rap, hip-hop, electronica—have compared their critics to the dull folkies who didn’t understand the times were a-changing, and a complex choice by a complex artist in a complex time became a parable: the prophet of the new era going his own way despite the jeering rejection of his old fans. He challenged the establishment: “Something is happening here, and you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?” He defined his own transformation: “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.” He drew a line between himself and those who tried to claim him: “I try my best to be just like I am, but everybody wants me to be just like them.” And he warned those wary of following new paths: “He not busy being born is busy dying.”

In most tellings, Dylan represents youth and the future, and the people who booed were stuck in the dying past. But there is another version, in which the audience represents youth and hope, and Dylan was shutting himself off behind a wall of electric noise, locking himself in a citadel of wealth and power, abandoning idealism and hope and selling out to the star machine. In this version the Newport festivals were idealistic, communal gatherings, nurturing the growing counterculture, rehearsals for Woodstock and the Summer of Love, and the booing pilgrims were not rejecting that future; they were trying to protect it.

Elijah Wald is the author of Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties. His ther books include The Mayor of MacDougal Street, inspiration for the film Inside Llewyn Davis; Escaping the Delta, about the myth and music of Robert Johnson; and How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ’n’ Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music. He has won a Grammy Award, an ASCAP-Deems Taylor award, and the American Musicological Society’s Otto Kinkeldey award; has taught blues history at UCLA; and travels widely as a speaker on popular music. He lives in Medford, MA.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com