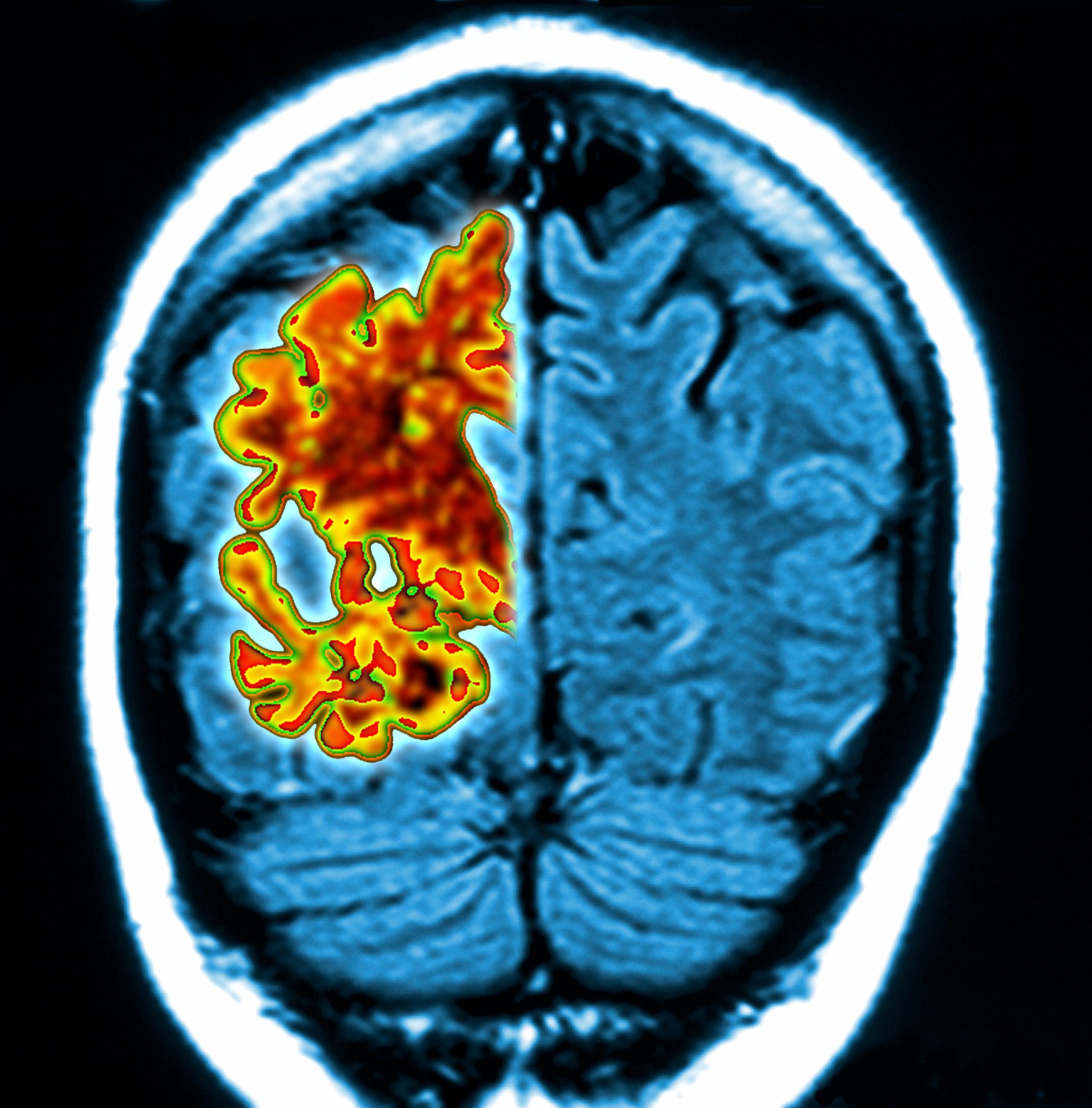

The latest breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s research focus on the time well before patients even know they might have the neurodegenerative condition. Studies so far have found evidence that the biological processes that cause the mental decline may begin 10 to 12 years before people first notice signs of cognitive decline. But in the most recent report published Wednesday in the journal Neurology, experts say that the disease may actually begin even earlier — 18 years earlier, in fact — than they expected.

MORE: Mental and Social Activity Delays the Symptoms of Alzheimer’s

For 18 years, Kumar Rajan, associate professor of internal medicine at Rush University Medical Center, and his colleagues followed 2,125 elderly people with an average age of 73 and who did not dementia. Every three years, the researchers gave the volunteers mental skills tests, and then compared these results over time.

When the looked at the group that went on to receive an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, they found that these people showed lower scores on their tests throughout the study period. In fact, their scores steadily declined with each test. For each unit that the scores dropped on the cognitive tests, the risk of future Alzheimer’s increased by 85%.

Into Oblivion: Documenting the Memory Loss from Alzheimer’s

MORE: Many Doctors Don’t Tell Patients They Have Alzheimer’s

Rajan stresses that the results only link cognitive testing scores on broad, group-level risk, and can’t be used to predict an individual’s risk of developing the disease. For one, more research will be needed to find the range of decline that signals potential Alzheimer’s dementia. But the findings do set the stage for studying whether such a non-invasive, easily administered test can, or should be, part of a regular assessment of people’s risk beginning in middle-age.

That way, he says, people may have a longer time period in which to hopefully intervene to slow down the disease process. Rajan plans to study whether brain-stimulating activities like crossword puzzles or learning a new language and social interactions can improve the test scores, and in turn slow the time to diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. At the very least, he says, the current data shows that there is a longer window of time in which people might be able to intervene in these ways and potentially delay Alzheimer’s most debilitating effects.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com