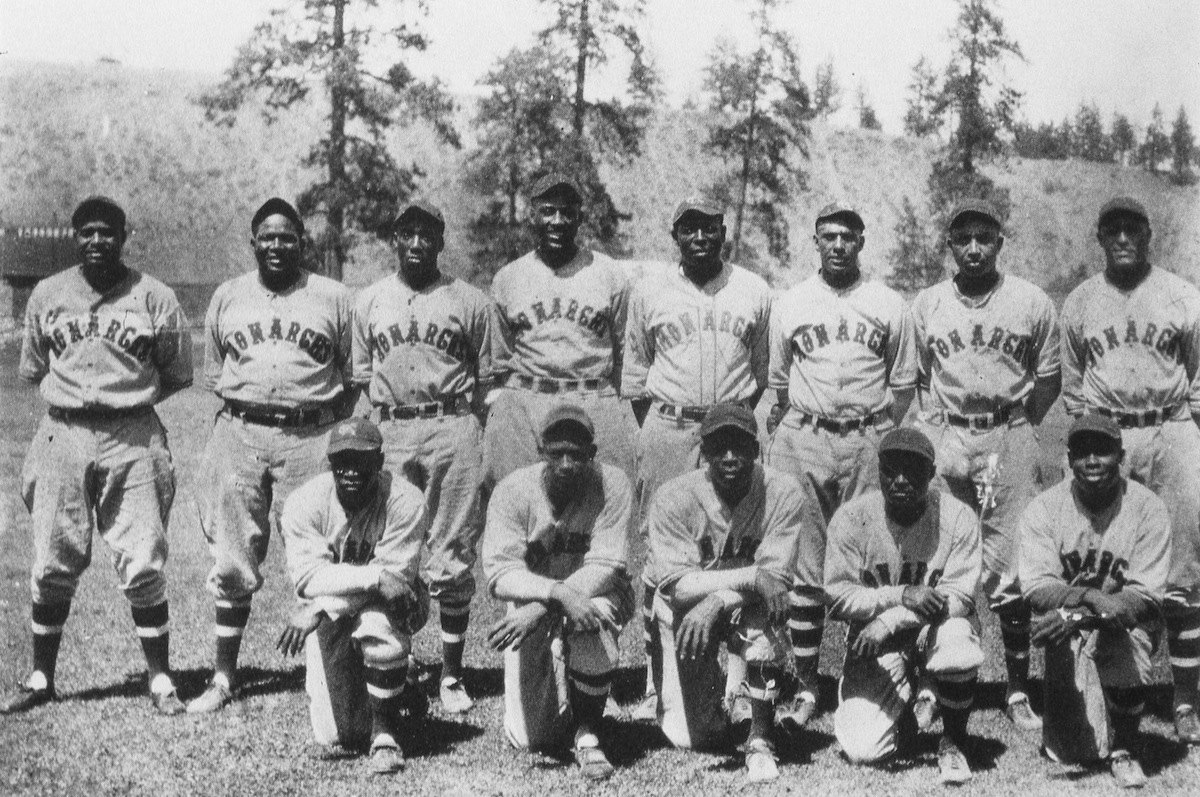

J. L. “Wilkie” Wilkinson, a baseball team owner, needed to put more bodies in seats. It was 1930, the year after the stock market had crashed, and the Depression was taking its toll. Not even baseball was safe: One team had folded; a whole league disbanded. Wilkinson owned the Kansas City Monarchs, a winning team, but their daytime games made it impossible for working fans to attend. Additionally, the Monarchs were members of the Negro National League and didn’t have their own stadium. Under the shadow of Jim Crow, where few stores and hotels would cater to them, playing baseball required lots of travel in unwelcoming conditions. And, while mostly black crowds attended the Monarchs’ games, the efforts to attract new white fans were fruitless.

Wilkinson yearned for a financial home run and tried everything to keep the team going. In the 1920s, he lowered the price of seats from $1.10 to $.75; he halved the price of tickets for women on Ladies Night. Now more desperate, Wilkinson, who was white, took a bigger gamble. He mortgaged everything he owned to pursue a radical idea: playing baseball at night, when fans weren’t at work. If he could just figure out how to help fans see the game, he figured, they would come. It wasn’t a totally new idea—night baseball had been batted about by professional and amateur teams for years; and a team from Independence, Kans., lays claim to hosting the first-ever such home game exactly 85 years ago, on April 28, 1930—but nobody had really made it work as a long-term solution.

The technology for nighttime baseball had significantly improved in the years since the first attempts had been made. Help came in the form of a mild-mannered Massachusetts-born General Electric physicist, William David Coolidge, who made floodlights possible. While Thomas Edison is credited with inventing the light bulb, his were short lived. The wire threads, or filaments, that they used to generate light burned out quickly or broke. Coolidge worked for years to make filaments with longer-lasting lives. The element tungsten, a silvery metal with the highest melting point on the periodic table, was an excellent candidate for a material, except that it had one major flaw. Tungsten snapped like chalk when drawn into a wire thread. When Coolidge “baked” tungsten, he eventually discovered, it became pliable. And, with Wilkinson’s pioneering idea, it was tungsten wire set in a bulb that would eventually beam light onto the baseball diamond.

Wilkinson’s great innovation was to commission the Giant Manufacturing Company of Iowa to make a portable lighting system. Six floodlights on telescoping poles nearly 50 ft. tall were mounted on flatbed trucks located throughout the field. The lights could go on the road with the Monarchs, an advantage not available to some of the other teams that introduced night games that same season. The electric lights were a sight to behold, since fewer than 10% of farms in America had electricity in the early 1930s. The novelty of the portable lights at baseball games, Wilkinson hoped, would act as the flame to the proverbial moth.

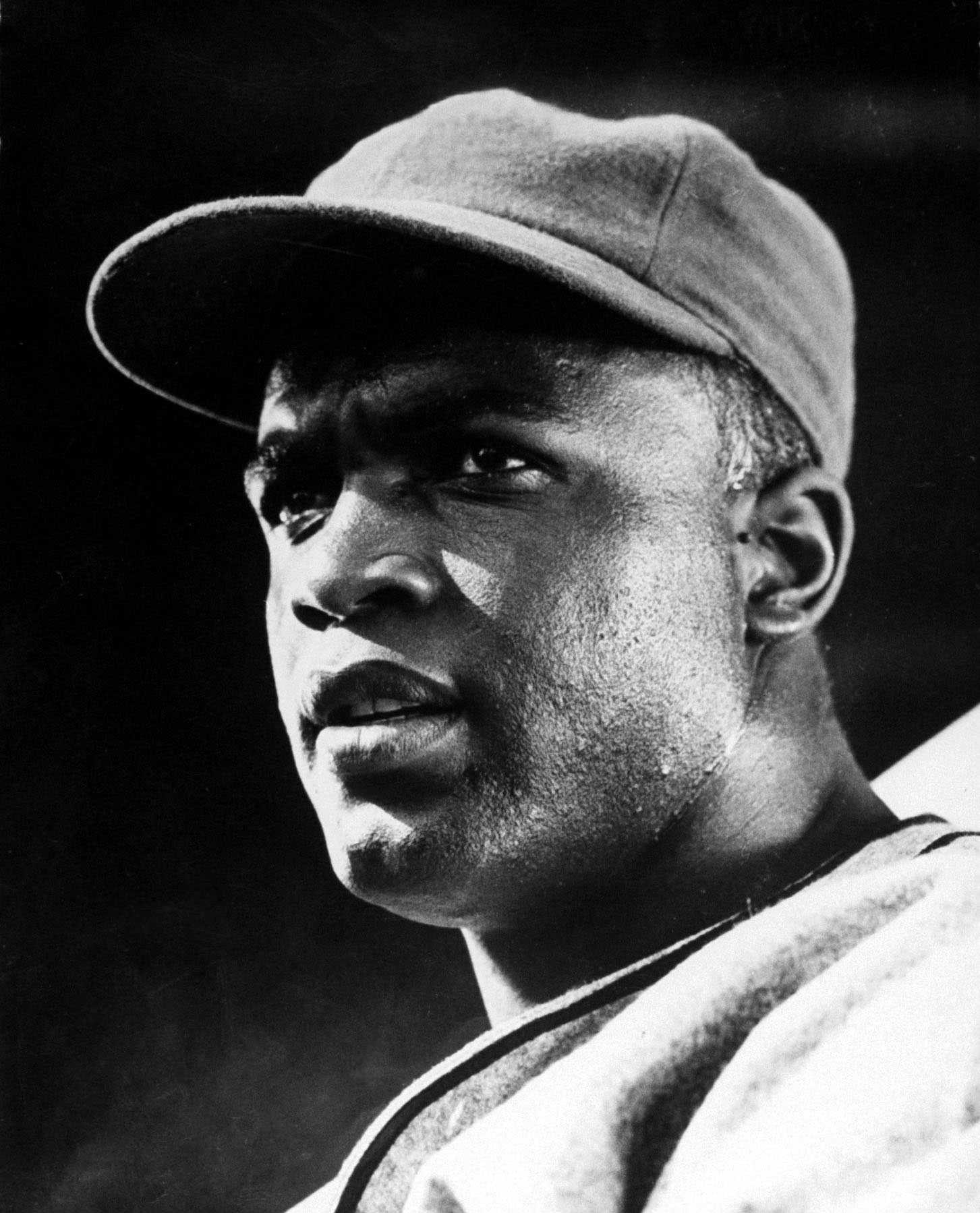

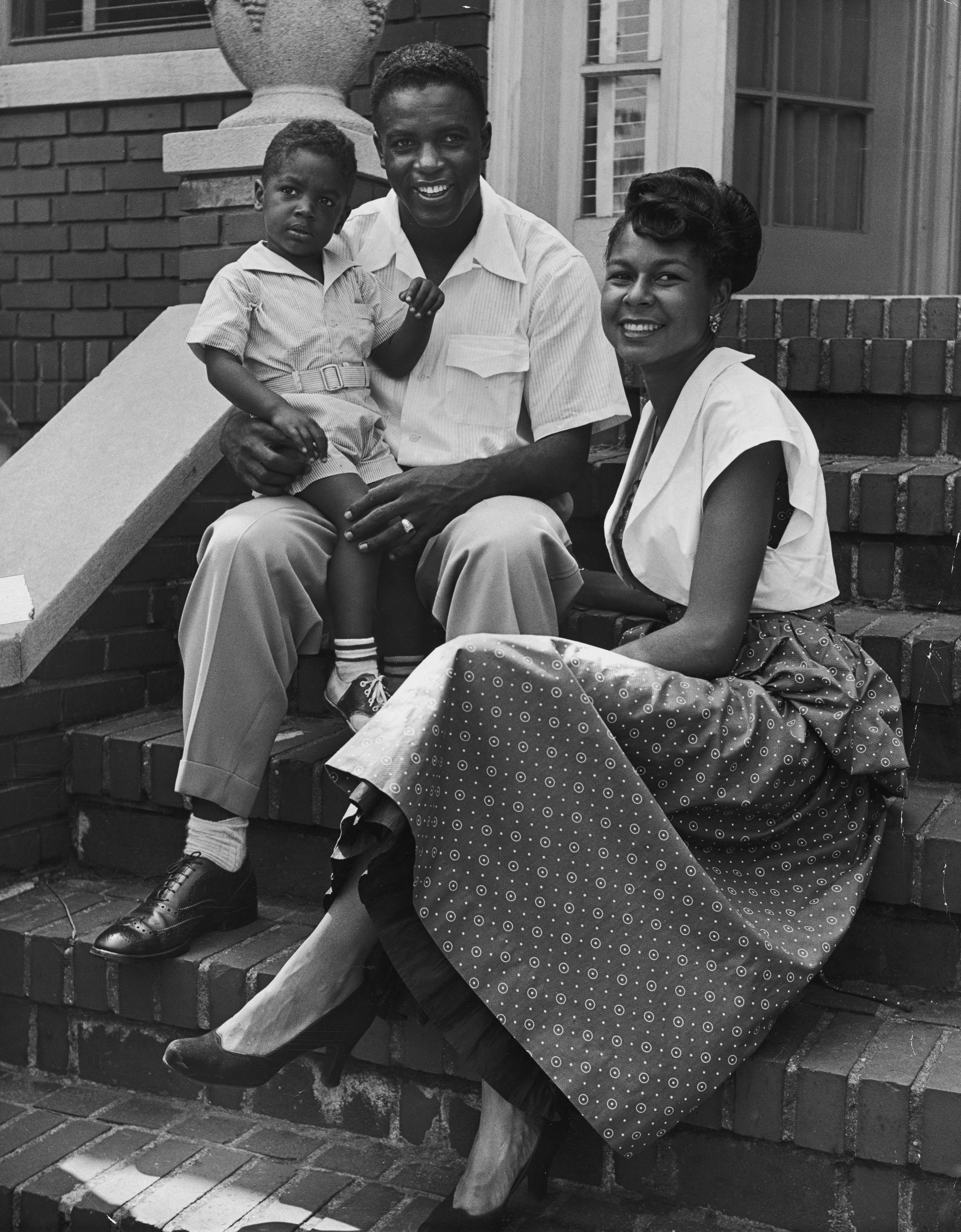

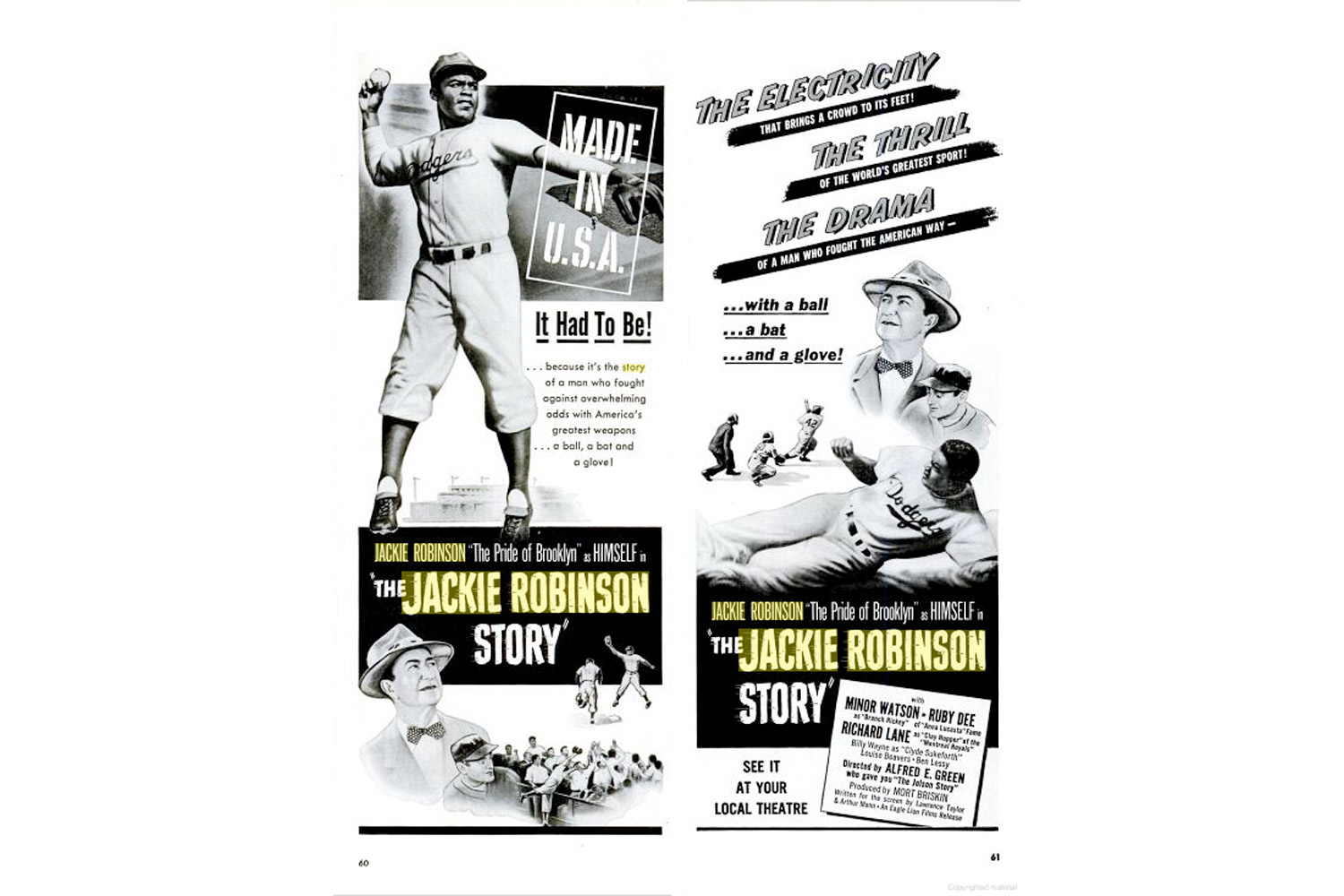

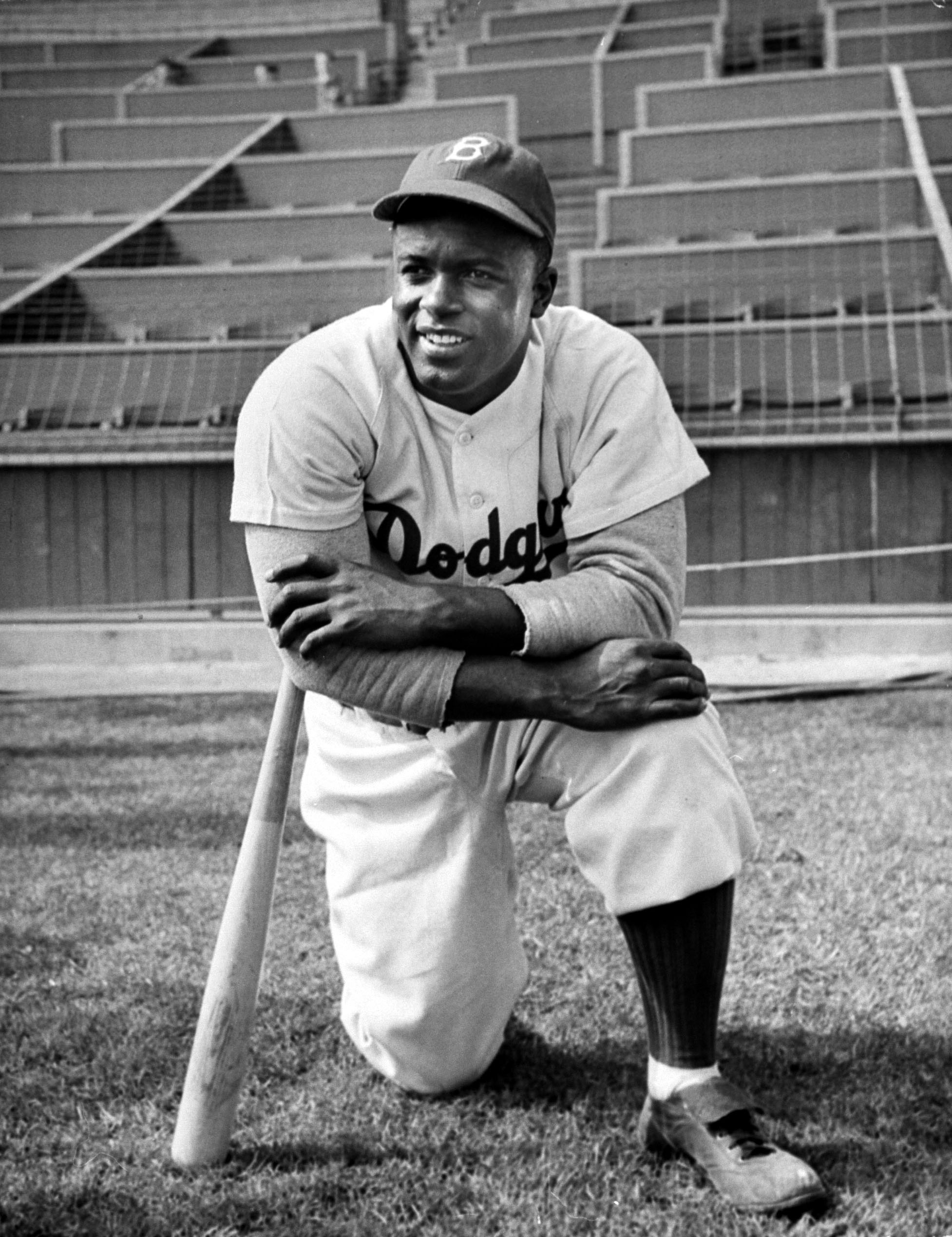

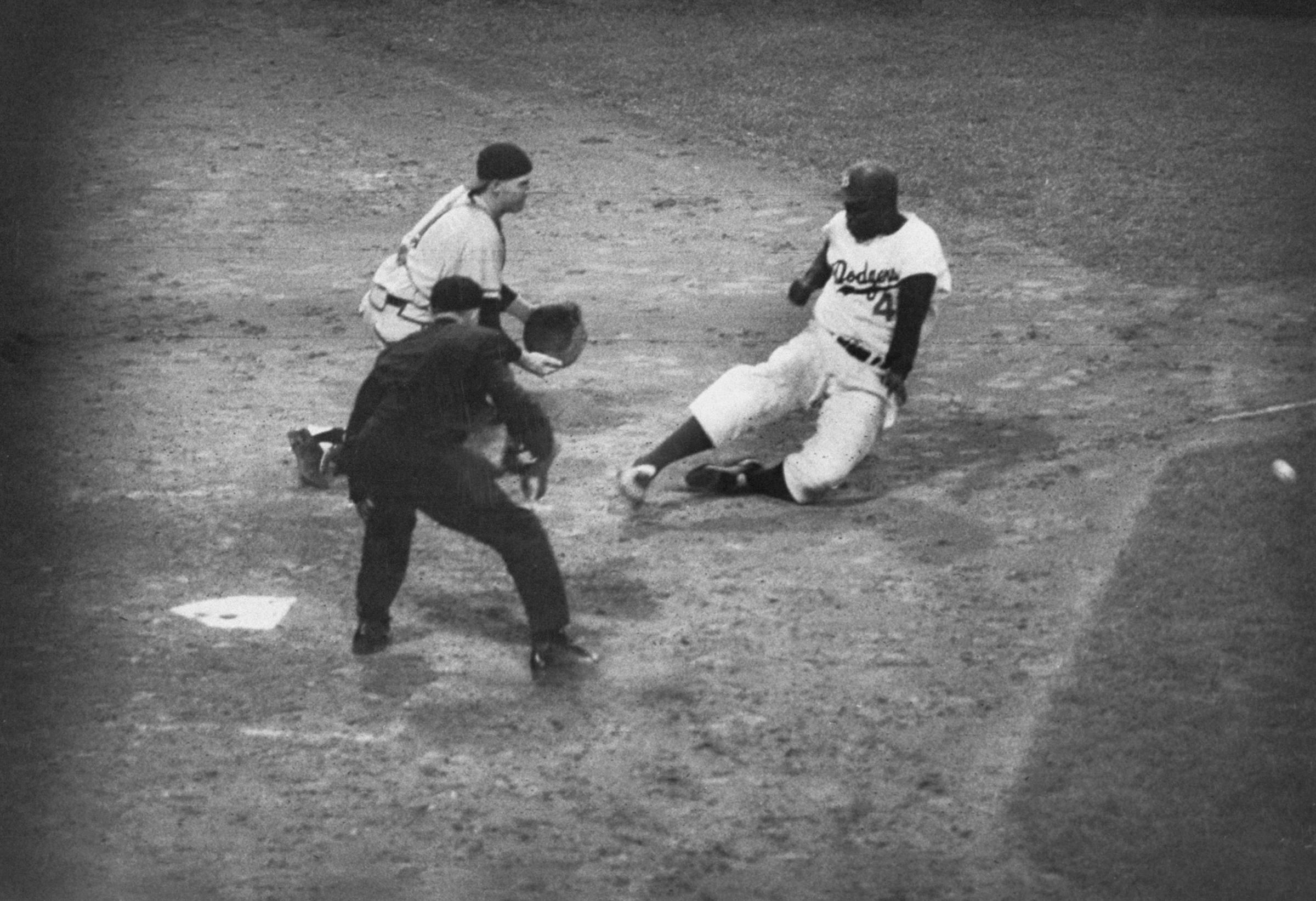

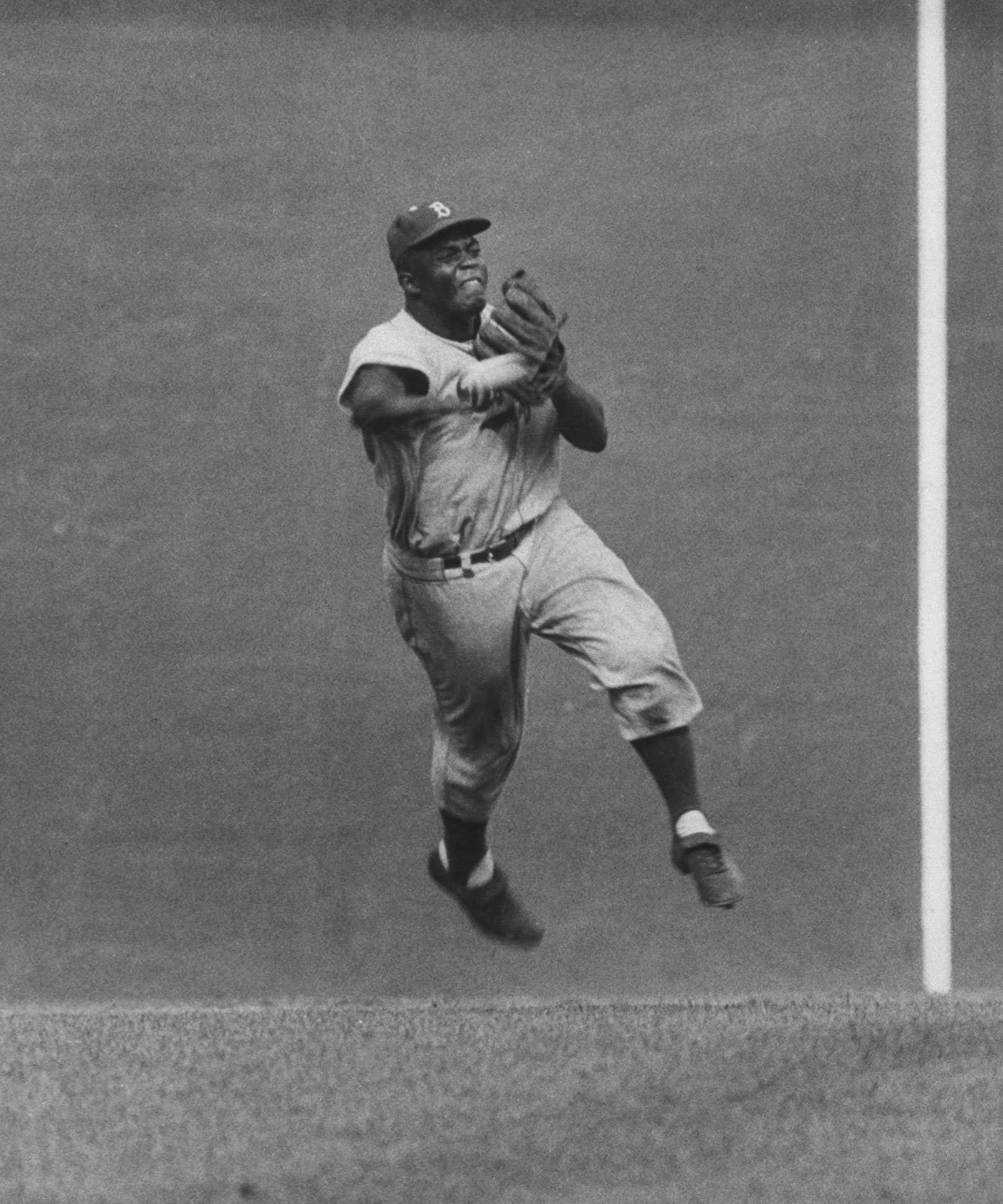

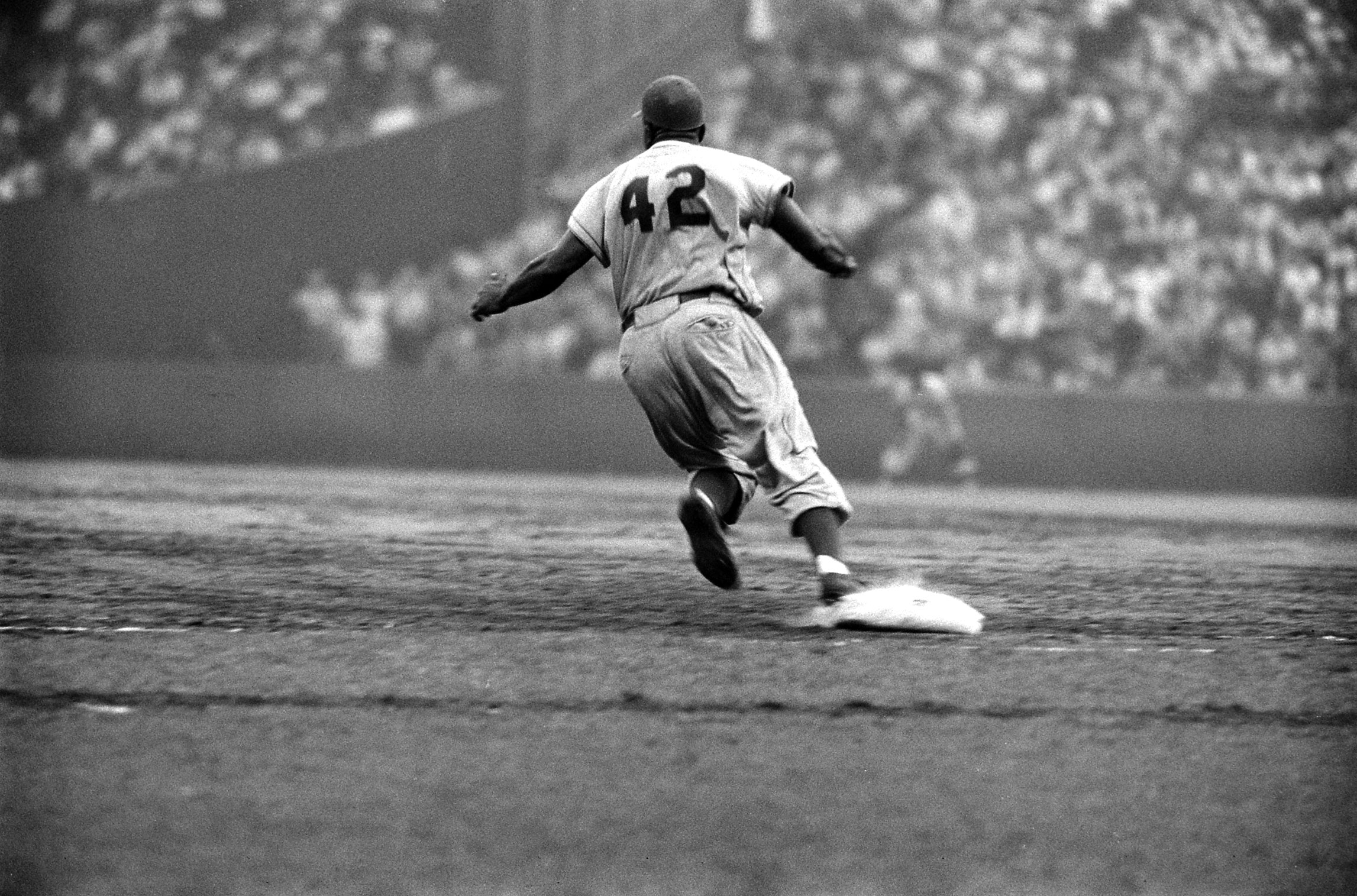

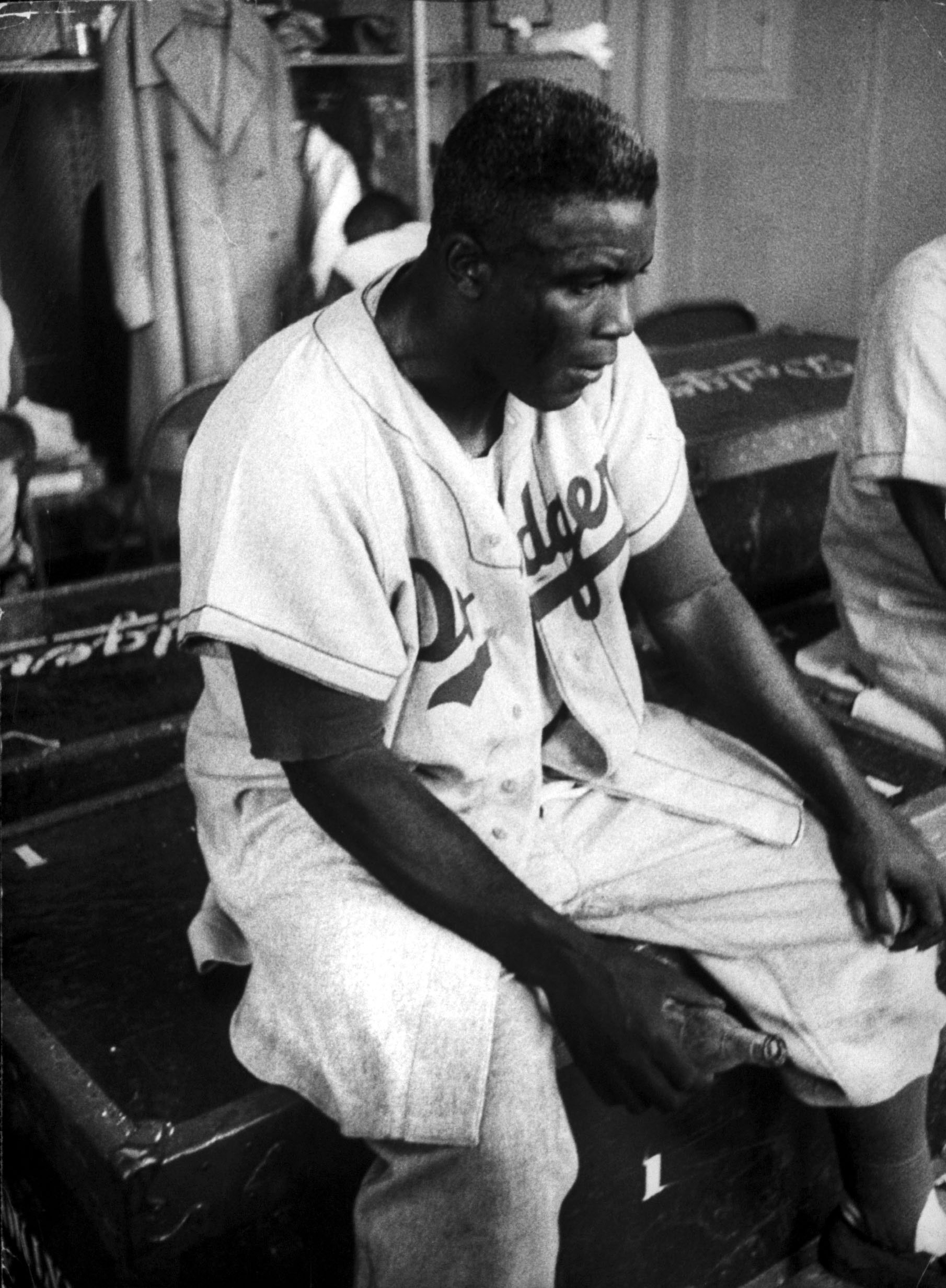

And it worked. With those lights the fans also saw the dawn of a new era—the beginning of nighttime baseball games, a full five years before Major League Baseball would follow their lead. Attendance that first Monarchs season grew from 5,000 to 12,000 to a peak of 15,000 people. Thanks to their portability, Wilkinson’s lights acted as beacons for fans of all races—and helped the Monarchs survive the Depression, which would have echoes throughout the history of baseball: Years later, Jackie Robinson would get his start with the Kansas City Monarchs, before moving on to the Brooklyn Dodgers, playing his first game April 15, 1947, and opening up baseball even more.

Ainissa Ramirez is a scientist and author (Newton’s Football, Save Our Science). She co-hosts a 2-minute science podcast called Science Underground.

LIFE With Jackie Robinson: Rare and Classic Photos of an American Icon

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com