In the early morning of April 21, 1865, the soggy streets of downtown Baltimore were packed with swarms of people. By 8 o’clock, the roads surrounding the Camden station were impassable. Work stopped. Schools closed. Stores emptied. And, the people, waiting patiently for a train, wept.

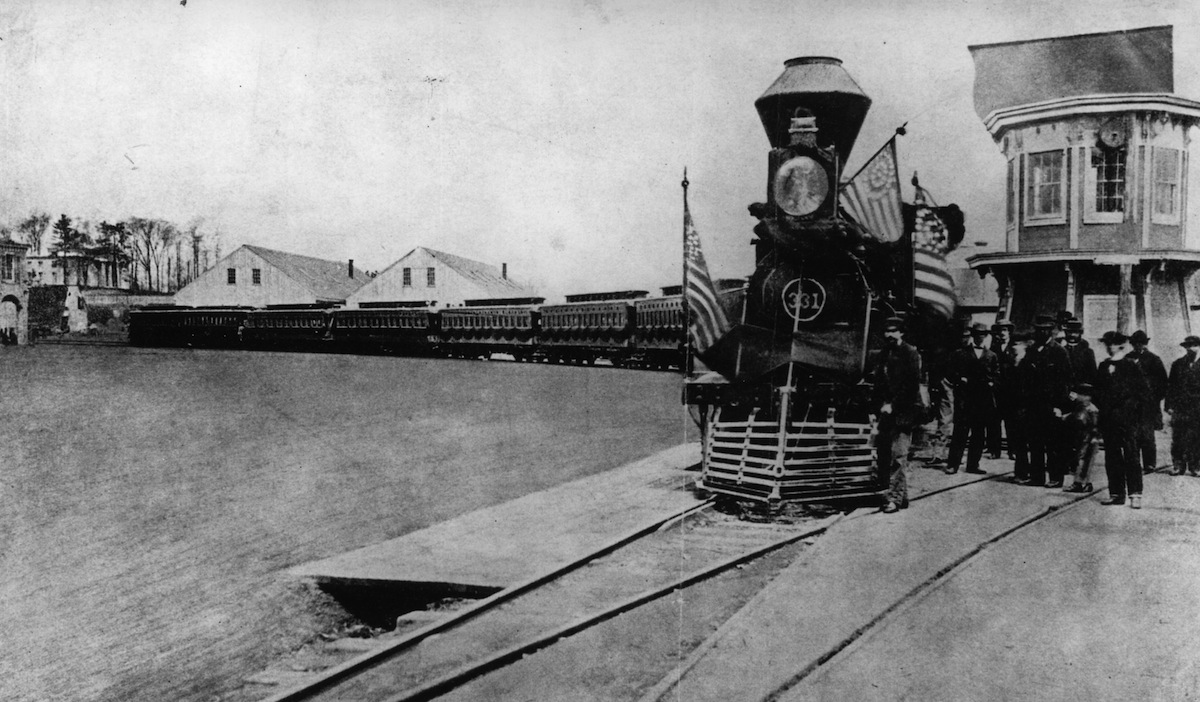

The train that chugged into the station at 10 o’clock contained the remains of Abraham Lincoln. He had died six days prior, on April 15, less than a week after the Civil War ended at Appomattox. Inside the train, dubbed the Lincoln Special, the late President’s body was dressed in the same suit from his second inauguration just six weeks earlier.

The people’s outpouring of grief begged that his funeral services extend beyond Washington. In an age before television or radio, the only way for a person to participate was to leave her farm or close his store and physically go to a funeral procession where Lincoln lay in state. Lincoln’s funeral train allowed the nation to mourn in unison by bringing him to them in a way that neither telegraph nor newspapers could satisfy. Over the course of 20 days, the train sojourned from Washington to Baltimore to Harrisburg to Philadelphia to New York to Albany to Buffalo to Cleveland to Columbus to Indianapolis to Chicago, and finally to Springfield, Ill.

Coordinating the transportation of Lincoln’s remains fell on the shoulders of the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. His was a temperament opposite to Lincoln’s, but he had kept a loyal vigil at Lincoln’s deathbed and took on the challenge of creating the biggest funeral that the country had ever seen. Stanton made this procession possible by designating the railroads as military domains, so the different railroad companies that ran the collection of lines were required to fully cooperate.

Orchestrating the 15 railroad companies involved was a mammoth undertaking. For that reason, Stanton created the Committee of Arrangements. Its members were “authorized to arrange the time tables with the respective railroad companies, and do and regulate all things for safe and appropriate transportation.” Still, scheduling the train also required a wrangling of various time zones between cities and states, which were more numerous and less systematic than today. Before standardized time began in 1883, most towns told time by high noon. Clocks had to be increased one minute for every 12 eastward or westward miles to keep the correct time. Noon in D.C. was 12:12 in New York, 11:17 in Chicago and 12:07 in Philadelphia. As such, the country was composed of ununified pockets—splintered by both war and local time—and this train, with its precious cargo, briefly threaded them together.

Lincoln’s funeral car was a magnificent carriage. The sides were painted a rich brownish-red, which was lovingly hand-polished to a shiny gloss with oil and rottenstone. The interior was decorated with plush green upholstered walls and black walnut molding. Pale green silk curtains cascaded along etched glass windows and three oil lamps beaconed from the car at night. With 16 wheels instead of the usual eight, it was a vehicle that paralleled those of European royalty. This special coach had three stately compartments and Lincoln’s casket sat in the end room. (The body of Lincoln’s departed son Willie, who had died in 1862 of typhoid fever, made the trip with Lincoln in the first room of this car.) As a presidential car, it had been originally designed to be Lincoln’s Air Force One. But here, festooned in black bunting and on its maiden voyage, it was now his mobile sarcophagus.

At each destination along the route, the train stopped and the honor guards, dressed in robin’s-egg-blue uniforms, carried Lincoln’s body in huge formal processions to viewing areas. Crowds waited for hours and many watched from windows or rooftops or tree limbs. In the halls, thousands of mourners, sometimes packed 12 bodies deep, stood weeping and waiting for a glimpse of the open coffin. For many, this was the very first time they saw Lincoln’s face, since photographs in newspapers were still new. As Lincoln grew closer to his resting place, the emotions of the nation heightened. In some whistle-stops, the number of mourners was greater than the town’s population.

Crowds who could not make it to the cities made their way to the train’s tracks. The locomotive engine, bearing a portrait of Lincoln in the front, chuffed at a cautious 20 mi. per hour and passed by train stations at a quarter of that speed. The engine was followed by nine cars: six passenger and baggage cars, a car for guards, a special car that carried the body and the last car for family and the honor guards. A pilot train ran about 30 min. ahead of the funeral train and announced Lincoln’s arrival by sounding a half-muffled bell, in which a leather pad was placed on half of the clapper to soften the strike. Those waiting trackside heard a rhythmic ringing of a clear tone followed by its muted echo and knew it was time to prepare. Bonfires were set along the route at night to push back the darkness, in an age before Edison, which made the evening air a curious mixture of smoke and lilacs in bloom.

There was a solemn eagerness as people lined the tracks day and night, rain or shine. At the sight of the trains, they stood back–some waving small flags, some standing silently, some singing hymns. Fifteen minutes later, a third train followed. When the final train passed, the crowds stepped into the tracks and watched it fade into the distance. Then, the moment was over.

Before Lincoln was set in his final resting place, his remains would be transported across the country on over 1,600 mi. of track. Millions of people participated. Nearly every American knew someone who attended memorial services or watched funeral processions or saw the train pass by. In these sad and dark days, the nation was stitched together in a way that it had never experienced before.

Ainissa Ramirez is a scientist and the co-author of Newton’s Football and the author of Save Our Science. She co-hosts a science podcast called Science Underground.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com