Slut.

Tart.

Whore.

That Woman.

Those were the words used to describe Monica Lewinsky, the once 22-year-old intern who had an affair with the President. She is 41 now and speaking publicly about the impact of that relationship for the first time. When those words weren’t used to describe her, they were simply known as what defined her.

Almost two decades later, those are the same words — though slightly updated — used daily to harass, threaten and humiliate young women and girls who deviate from the sexual (and sometimes not-so-sexual at all) norm, both at school and online.

History met the present recently at a Manhattan performance of a play called SLUT, where Monica Lewinsky watched the story of a teen girl who is assaulted, reports it, and is slut-shamed by her peers. I sat next to Lewinsky as she watched the drama play out. At the end, she stood up, surveyed the young faces in the audience, and spoke: “Thank you,” she told the crowd, “for standing up against the sexual scapegoating of women and girls.” Afterwards, girls crowded around Lewinsky to express their own gratitude for her outspokenness.

The Lewinksy scandal broke in in 1998. SLUT the play takes place today. In between, the word has been used by Rush Limbaugh to discredit Sandra Fluke a law student who spoke up for birth control; to debate the validity of sexual assault claims; and more often than one could count, to talk viciously about women on the Internet. (Just this week, Ashley Judd proclaimed she would sue her slut-shaming harassers on Twitter.)

What is it about the word slut that is still so potent?

Slut didn’t begin as a bad word — or a word for women at all — but merely an “untidy” one. Chaucer (yes, that Chaucer) put it in print in the early 1300s, referring to a sloppy male character as “sluttish” in The Canterbury Tales.

But if the word was used for men more broadly it was only for a second: by the 1400s, it had morphed into a term for maids and unkempt, dirty women (like actually dirty, not sexually dirty). It wasn’t long before that notion was infused with sexual connotations. Today, the term is defined by Oxford Dictionary as a woman who “has many casual sexual partners” or one with “low standards of cleanliness” — though it’s clear that in our modern lexicon, those two might as well be one and the same.

Sure, there have been positive usages or attempts to take slut back: Kathleen Hanna famously scrawled the word across her stomach while on stage with Riot Grrrl in the 90s; there is the SlutWalk movement, an effort to reclaim the word.

But by and large one definition remains: Slut is loaded. Slut is bad. Much in the way that Lewinsky became a kind of public symbol, said the linguist Robin Lakoff, “of all that is sexually loathsome and scary about women,” the word slut — and its linguistic sisters, ho, whore, tramp, and skank — is a stand-in for the same: used to describe women who deviate from the norm.

“Girls are still targeted when they cross some kind of boundary,” said Eliza Price, a 16-year-old cast member in the SLUT play, which is produced by an all-girl theater group called the Arts Effect.

But that boundary can almost anything: clothing, behavior, attitude or something else. As a group of Mississippi teens described it to the author Rachel Simmons, in her book, Odd Girl Out, a girl can be a slut — or in this particular interview, a “skank” — if she sits with her legs open, wears baggy clothes, wears tight clothes, talks in slang, gets into fights, or shows too much PDA. “In other words: almost anything,” said Simmons. “‘Slut’ and its cousin ‘skank’ are used to denote girls who take up space and break the good girl rules.”

And sometimes that has nothing to do with sex. Leora Tanenbaum, the author of a new book, I Am Not a Slut, has interviewed girls and women who’ve been labeled with the word — coining, in 1999, the term “slut-bashing,” which would later evolve into “slut-shaming.” But being called a slut, she found, actually had little to do with whether or not these girls were sexually active. Rather, anybody could be called a slut, she said. The word was a catch-all to discredit women; for young women, it was a way to define them before they got the chance to define themselves.

And while words like bitch have an action associated with them — i.e., if you change your behavior you might be able to shed the label — the word slut is forever.

“Once you’re labeled a slut, it’s pretty much impossible to rid yourself of it,” explains Winnifred Bonjean-Alpart, 17, the lead actress in the play and a high school student in New York. As another young actress explained it: You can be valedictorian, class president and prom queen, but if more than one person calls you slut, all that gets wiped away.

And the Internet makes that even more the case. “In the 90s, when girls would come to me and say ‘I’m the slut in my school and I can’t bear it, what should I do?’ One of the things I would say is ‘Have you looked into transferring to another school?’” said Tanenbaum. “But you can’t say that anymore, because her reputation is going to follow her. You can’t go off the grid.”

The way slut as epithet plays out is multifold:

It’s the reason young women are so obsessed with their “number”— how many sexual partners they’ve had. It might explain why some women lie to their healthcare providers about those numbers, even when it’s not in their best interest.

It’s the reason why, on more than one occasion, as a young woman I would say “no” when I really wanted to say “yes”: yes, of course, would be considered slutty. (You can imagine how that plays into the complicated conversation we’re now having about consent.)

In one case that Tanenbaum describes, a young college woman believed that being called slut contributed to the reason she was raped. “He must have thought, ‘Well, she sleeps around all the time, so she’ll say yes to me,’” the woman told her.

In Monica Lewinsky’s case, that label is the reason she still can’t find work, and has largely stayed out of the public eye for close to a decade. As she said in her TED talk this past week, “It was easy to forget that ‘that woman’ was dimensional, had a soul and was once unbroken.”

Back in 1998, Lewinsky was condemned by the left and the right, by men and women alike, even self-proclaimed feminists (including the New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, whose columns on the scandal of President Clinton’s affair and “slutty” Monica Lewinsky won a Pulitzer Prize). Today Lewinsky would be likely to have defenders: there are simply more avenues to push back against a singular media narrative; and we have a new language with which to talk about it.

But the word still has the power to wound, diminish and discredit — as so many victims of sexual assault can attest. Which begs the question: Instead of discrediting women, can we simply discredit the word?

Jessica Bennett is a contributing columnist at Time.com covering the intersection of gender, sexuality, business and pop culture. She writes regularly for the New York Times and is a contributing editor on special projects for Sheryl Sandberg’s women’s nonprofit, Lean In. You can follow her @jess7bennett.

Read next: Monica Lewinsky TED Talk: ‘I was Patient Zero’ of Internet Shaming

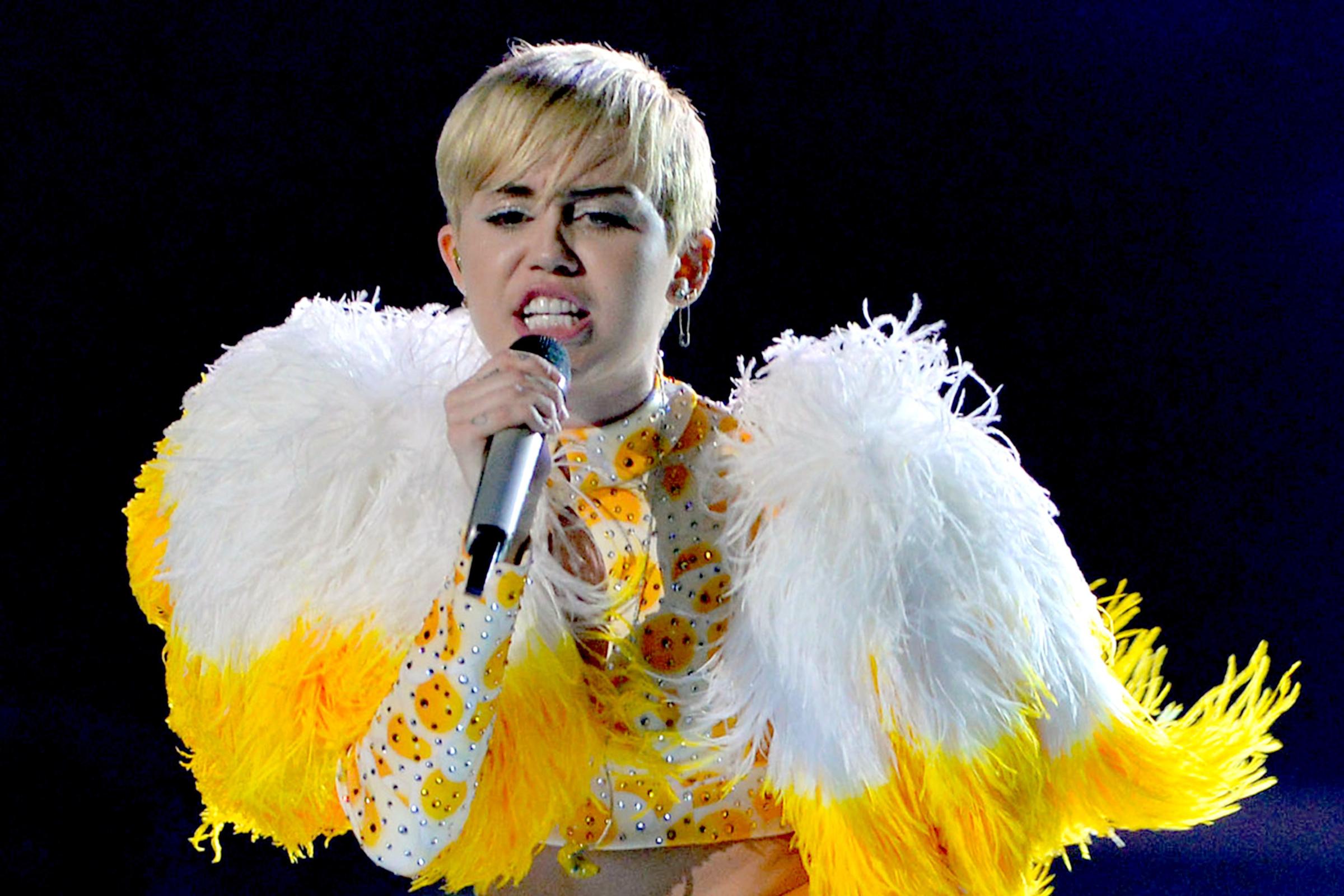

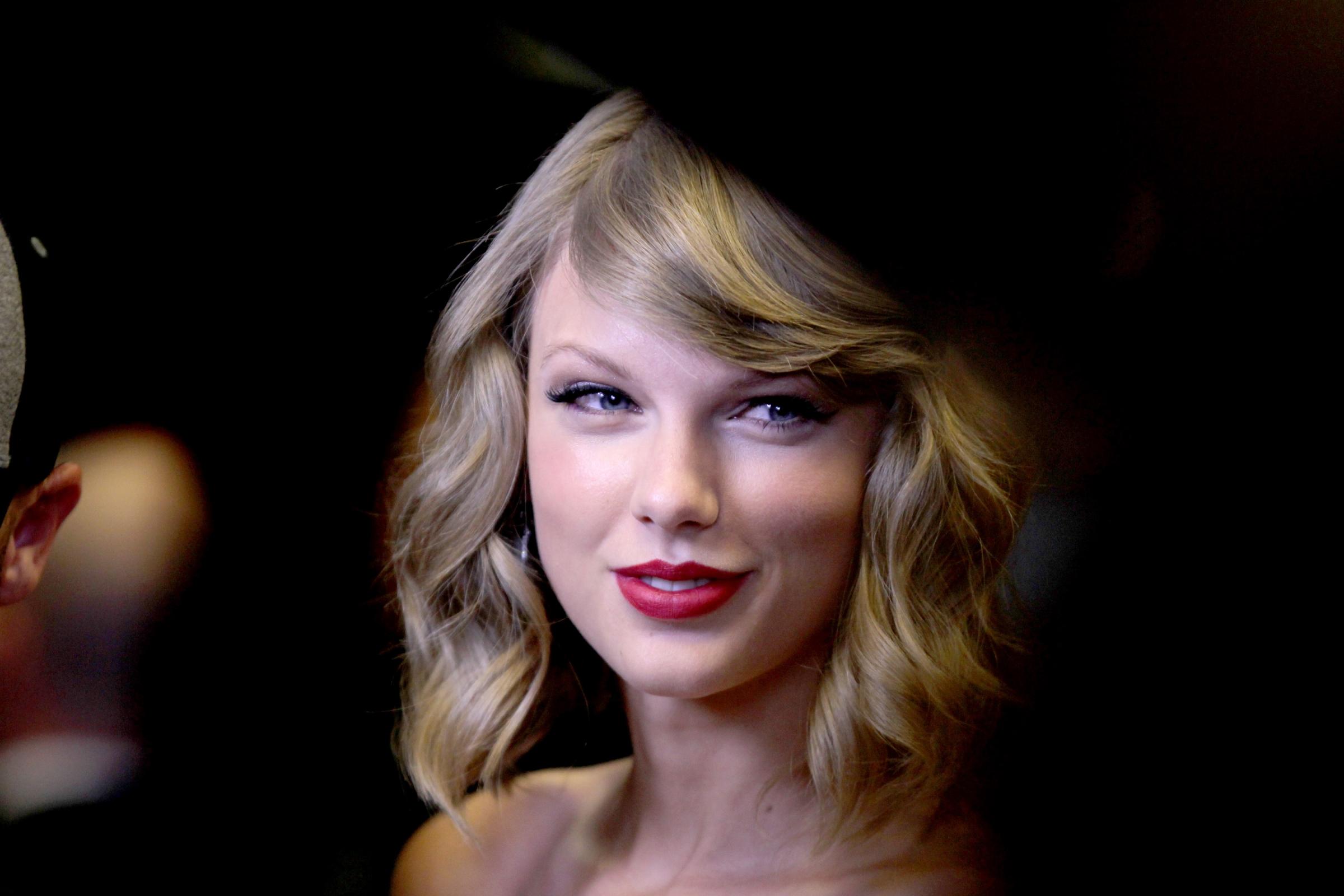

Here's What 20 Famous Women Think About Feminism

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com