Scientists are closer to a potential stem cell treatment for type 1 diabetes.

In a new article in the journal Cell, Douglas Melton, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (and one of the 2009 TIME 100) and his colleagues describe how they made the first set of pancreatic cells that can sense and respond to changing levels of sugar in the blood and churn out the proper amounts of insulin.

It’s a critical first step toward a more permanent therapy for type 1 diabetics, who currently have to rely on insulin pumps that infuse insulin when needed or repeated injections of the hormone in order to keep their blood sugar levels under control. Because these patients have pancreatic beta cells that don’t make enough insulin, they need outside sources of the hormone to break down the sugars they eat.

MORE: Stem-Cell Research: The Quest Resumes

Melton started with two types of stem cells: those that come from excess embryos from IVF procedures, and those that can be made from skin or other cells of adults. The latter cells, known as iPS cells, have to be manipulated to erase their developmental history and returned back to an embryonic state. They then can turn into any cell in the body, including the pancreatic beta cells that produce insulin. While the embryonic stem cells from IVF don’t require this step, they aren’t genetically matched to patients, so any beta cells made from them may cause immune reactions when they are transplanted into diabetic patients.

Both techniques, however, produced similar amounts of insulin-making beta cells—something that would have surprised Melton a few years ago. But advances in stem cell technology have made even the iPS cells pretty amenable to reprogramming into beta cells. Melton’s group tested more than 150 different combinations of more than 70 different compounds, including growth factors, hormones and other signaling proteins that direct cells to develop into specific cell types, and narrowed the field down to 11 factors that efficiently turned the stem cells into functioning beta cells.

MORE: Woman Receives First Stem Cell Therapy Using Her Own Skin Cells

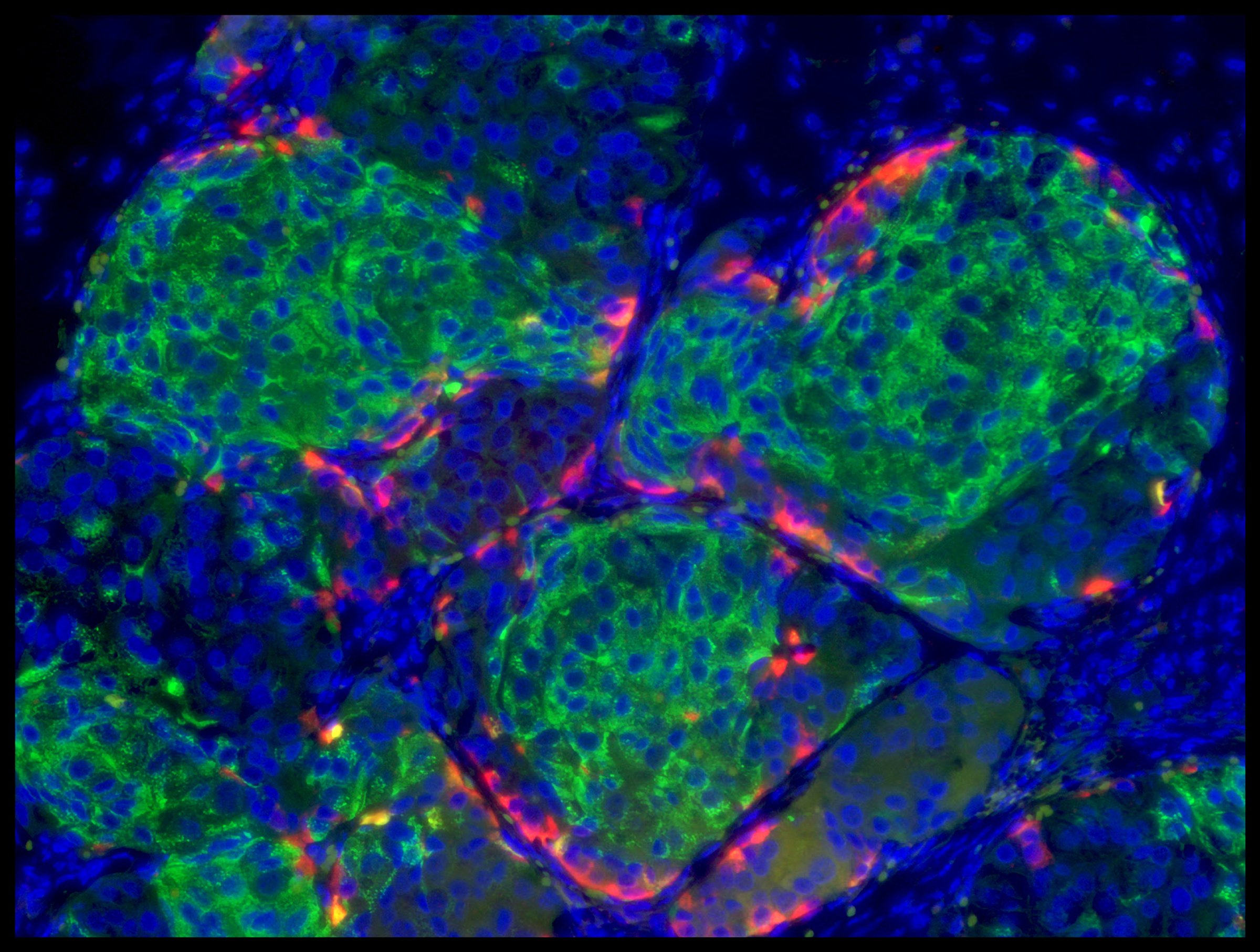

The two populations of stem cells churned out hundreds of millions of insulin-making cells, which is the volume of cells that a patient with type 1 diabetes would need to cure them and free them from their dependence on insulin. An average patient, says Melton, would need one or two “large coffee cups” worth of cells’, each containing about 300 million cells. Melton and his team then conducted a series of tests in a lab dish to confirm that the cells were functioning just like normal beta cells by producing more insulin when they were doused with glucose, and less when glucose levels dropped. That was a huge advance over previous efforts to make beta cells from stem cells—those cells could produce insulin, but they didn’t respond to changing levels of glucose and continuously pumped out insulin at will.

Next, the scientists transplanted about five million of the stem cell derived beta cells into healthy mice, and two weeks later, gave them an injection of glucose. About 73% of the mice produced enough insulin to successfully break down the sugar. What’s more, that was similar to the proportion of mice responding to glucose after getting a transplant of beta cells from human cadavers. That was especially encouraging since some type 1 diabetics currently receive such transplants to keep their diabetes under control. “We’ve now shown that we can produce an inexhaustible source of beta cells without having to do to cadavers,” he says.

MORE: First Stem Cells Cloned From Diabetes Patient, Thanks to Egg Donors

Taking the tests even further, the group showed that even mice that were already diabetic showed improved blood sugar levels after receiving a transplant of the stem cell beta cells—in other words, the transplanted cells effectively cured their diabetes. “We showed you can give three sequential challenges of glucose—similar to breakfast, lunch and dinner—and the cells responded properly,” says Melton.

But he acknowledges that as exciting as the advance is, it only solves half the problem for those with type 1 diabetes. The reason their beta cells aren’t able to make enough insulin may be due to the fact that they are attacked by the body’s own immune system for reasons that scientists still don’t understand. So the next step in turning these findings into a potential therapy is to find ways to protect the beta cells from destruction, either by encapsulating them in a mesh-like device similar to a molecular tea bag, or finding ways to genetically modify them to carry ‘don’t attack me’ proteins, the same way that fetal cells do so that an expectant mother’s immune cells don’t attack the growing baby.

MORE: Stem Cell Miracle? New Therapies May Cure Chronic Conditions like Alzheimer’s

“It’s taken me 10 to 15 years to get to this point, and I consider this a major step forward,” says Melton, who began researching ways to treat type 1 diabetes when first his son, then his daughter were diagnosed with the condition more than two decades ago. “But the longer term plan includes finding ways to protect these cells, and we haven’t solved that problem yet.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com