We’ve been hearing a lot of about angry black women this week. A New York Times television critic used that phrase recently to describe Shonda Rhimes, producer of breakthrough hit shows featuring African American women like Scandal, Gray’s Anatomy and How To Get Away With Murder which premiered on Thursday. The Times piece launched a hot debate about race and the media prompting a long response from the paper’s public editor on Wednesday. That’s a conversation we should be having, but beyond those fundamental questions, the fracas left me wondering where the term “angry black women” originated and what goings on made the term stick.

By the time we’re adults, most black women have lots of reasons, big and small, to be furious whether it’s pay inequities or the outrageous injustices that are regularly inflicted upon our fathers, brothers, sons and husbands. But looking around, I don’t know where all the angry black women are. Mostly we’re working. Anger might just be a luxury we don’t have. And I’m not sure public fury is something we feel safe expressing even when we should.

Just this summer, a friend mine, well-educated, well-travelled, successful and black, offered to house sit and take care of my dog Grace. She’s done this before and usually her boyfriend would join her while she walked Grace in the park down the street from my home. On one particular night on their walk, three police cars pulled up and asked her what she and her boyfriend were doing. Stunned, scared and confused, she cautiously replied “walking the dog.” They showed their ID to the officers and went on their way. My friend then phoned to tell me what had happened. She was clearly shaken but not angry, though she had every right to be.

Before that, I spent weeks watching Trayvon Martin’s mother defend her murdered son with strength and grace but never anger, an emotion she had every right to under the circumstances. I thought of my sons and wondered how she kept the rage at bay. But she did. And now there’s Michael Brown, and another mother suffering but not raging.

When I explain to my sons (who happen to be half white ) that while their friends jump fences to take the shortcut home , they absolutely should not. Why? They ask me. I search for the right words. I resent that I have to have this conversation with them, I resent that I worry about them when they pull up their hoodies. Does this make me an angry black woman?

I was raised being told that education is the great equalizing factor in America, but the officers in my Southern California neighborhood didn’t ask about my friend’s expensive degree when they stopped her. I don’t know what they were thinking. And while I do know that so very much has changed since my mother had to enter through the back door in order to go to the movies in Lexington, Ky., so much has remained the same. And that includes having a TV critic look at Shonda Rhimes’ career and decide to measure the complex black female characters she’s brought into our lives against a cartoonish stereotype.

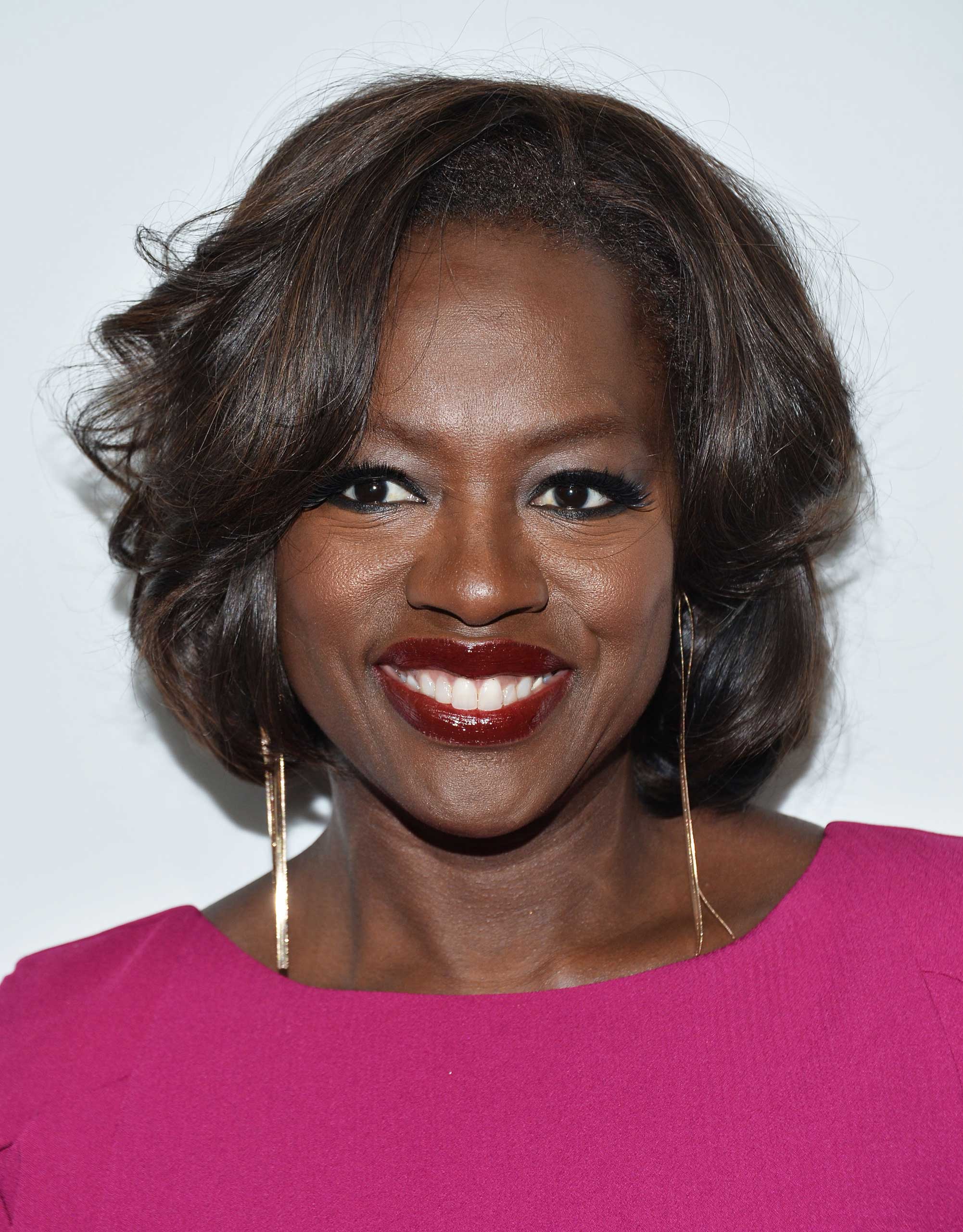

The piece should serve as reminder that it is still remarkable to see 49-year-old Viola Davis as the star of a prime time drama, and, for that matter, to see Michelle Obama in the White House. This is because we are still being measured against those stereotypes and still learning to climb past them. Legendary actress Ruby Dee once told me that for black women, life is “like going to the ocean and only being allowed a cup of it.” And when I think of Shonda Rhimes and what she has done with that cup, I’m proud. She is gloriously swimming in the all of it and furthermore, she brings friends … Viola Davis, Kerry Washington to name a few.

When I look at Tea Leoni or Kerry Washington I don’t see much difference between them. When I look at Viola Davis and Meryl Streep I am in awe, equally. But as a black actress and black woman, I realize that Davis and Washington’s roads have been very different from their counterparts. Narrower and steeper to say the least.

And for the black women who are watching these actresses move ascend in the cultural universe, there’s pride. Rhimes’ heroines are us. We don’t spend our days talking about being black, and we come in different shapes and sizes, and yes different colors. Some of us are weak and some of us are strong. And some of us are even angry, especially when someone who has no experience in our world makes a judgement about what we’re feeling.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com