It’s become a sadly familiar American routine. The shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., bore many of the hallmarks of the other school shootings that have shocked the nation over the course of the last weeks, months and years. Among those similarities was the weapon used by accused shooter Nikolas Cruz: the AR-15.

This semiautomatic version of the U.S. military’s M-16 infantry rifle and similar weapons have been used in most of the deadliest mass shootings in the last decade, including the one at Sandy Hook Elementary School. In some states like Florida, they’re easier to buy than a handgun.

So how did a military-style weapon become so widespread among civilians?

The answer requires going all the way back to the arms buildup during the Cold War, as C.J. Chivers describes in The Gun, a book on the invention of the assault rifle. Soviet Senior Sgt. Mikhail T. Kalashnikov is credited with developing the Kalashnikov rifle more commonly known as the AK-47 in the late 1940s. (“AK” stands for Avtomat Kalashnikova, the automatic by Kalashnikov.) The weapon eventually made its way to other communist countries, such as China and Vietnam. As Chivers described this week on the New York Times’ The Daily, when Americans found themselves “outgunned” in Vietnam in 1962, Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara ordered the Pentagon to make one to match it. The result was the M16. A lighter semiautomatic-only version of was available to civilians shortly after. That gun was the AR-15.

Civilians started to be able to buy the weapons shortly after they were developed for the military, but Chivers argues that doing so was still relatively uncommon. Many American gun-owners didn’t know or didn’t think about the option of owning a semiautomatic weapon.

That changed after a shooting at a Stockton, Calif., elementary school on Jan. 17, 1989, that left 5 dead and 29 wounded.

“Before Stockton, most people didn’t know you could buy those guns,” Chris Bartocci, a former employee of AR-15 manufacturer Colt and author of Black Rifle II, told CNN. He argues that people went out and bought the weapon after reading and hearing the news reports about the school shooting.

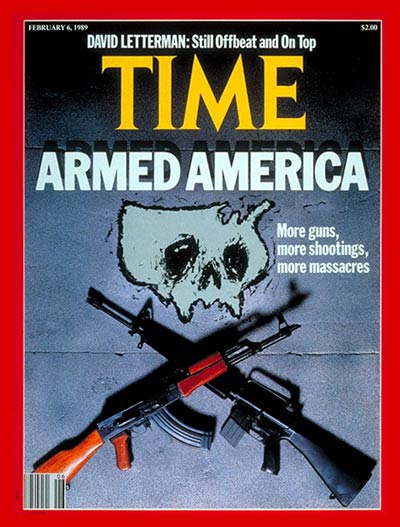

The Feb. 6, 1989, TIME cover story tried to make sense of how the gunman got a hold of a Chinese-made semiautomatic weapon in the first place. It reported that as trade increased following the normalization of relations, so did imports of Chinese copies of the AK-47, “which soared from a mere 4,000 a year as recently as 1985-86 to more than 40,000” in 1988. AR-15 sales went up too.

Also boosting sales was another one of the major domestic stories of the 1980s: the crack epidemic. “Law-enforcement officials note that the rise of semiautomatic weaponry parallels almost exactly the virtual takeover of parts of big cities by crack dealers,” the story noted. Robert Stutman, who ran the Drug Enforcement Administration’s New York State operation back then, told the magazine that “the paranoia induced by the drug, which most of the traffickers use themselves, makes them pick the best weapons available for protecting themselves, and they have the money for it.”

Then, when the police couldn’t match the dealers’ firepower, citizens who felt unsafe started buying these weapons themselves for self-protection:

The final and most dismaying turn in this cycle: responsible, law-abiding citizens — afflicted by a lack of confidence in the police, reading every morning and watching on TV every night the stories about shootouts endangering innocent bystanders — start arming themselves in case they have to join the battle. It used to be that the great majority of American gun owners bought their weapons for hunting or sport (target shooting, for instance). But recent surveys show nearly 50% mentioning self-protection as their primary reason. Says Mark Warr, a sociologist at the University of Texas: ”It’s a giving up on the system. People have lost confidence in the ability of local government to control crime. There is a growing feeling that ‘We must do it ourselves.'”

As that mentality spread, more Americans purchased military-style weapons for non-military self-defense purposes.

When the school shooting in Stockton occurred, some people responded by seeking to put an end to that trend. As Chivers has noted, the event “was part of the impetus for bans on assault-style weapons at the state and national level.” President Bill Clinton signed the most famous one in 1994, which included the AR-15 and other versions of military-style semiautomatic rifles.

At the same time, the news about the shooting raised awareness that military-style weapons were in fact available for purchase by civilians. In the midterm elections after the ban passed, Clinton’s party lost a net 54 seats in the House and eight in the Senate, giving Republicans a majority in both chambers of Congress for the first time since 1952. And Chivers argues that the conversation about the ban, ironically, helped raise awareness of the AR-15 and its variants even more, thus increasing demand.

Congress didn’t renew the ban when it came up for reauthorization. Because of the political fallout, Democrats “tended to look the other way” when it expired in 2004, as TIME previously reported. In the years since, fear that a ban would return — and fear of increased restrictions on gun-ownership in general — have at times driven increased purchases.

By 2013, the National Rifle Association reported that Americans owned about five million AR-15s.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com