When an American man is reunited with a Dutch painting in a German town on Thursday, the international meeting will come after eight years of work to establish the proper ownership of the painting — and eight decades after it was confiscated by the Gestapo.

The work in question is Holländisches Platzbild, often translated as “View of a Dutch Square.” It’s a copy of a painting by the 17th century Dutch Baroque-era painter Jan van der Heyden; the original is held by the Louvre and the copy was perhaps made by the artist himself. Since 1963, it has hung in the building of the association for the Roman Catholic cathedral depicted in the painting, St. Victor’s, in the town of Xanten, in northwest Germany. The cathedral has an interesting link to the 20th century German past: Anti-Nazi German Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen, whom the Nazis would accuse of sympathizing with “the corrupters of our race,” condemned Nazi racial laws in a 1936 speech there.

But that’s not the only link between the painting and that brutal chapter of history.

John Graykowski, 65, grew up hearing about his great-grandparents Gottlieb and Mathilde Kraus, who were part of Vienna’s Jewish elite. Photographs show them traveling in a chauffeured black limo, and their daughter Marie “Mitzi” Kraus meeting the current Queen Elizabeth II in the 1950s. Graykowski, a D.C. lawyer, had also heard his great-grandparents collected art, but had no idea how much they owned. When the family fled Vienna in the run-up to the Holocaust, that collection was left behind. Though his great-aunt told him the family had tried to track down some of the collection in the 1960s, they’d given up after not hearing back from the German government.

But around 2002, “completely out of the blue,” Graykowski and his uncle Alex Heingartner were contacted by an organization helping the Austrian government. Its mission was to implement a 1998 Austrian law that led to the creation of a commission for investigating the provenance of artworks owned the state and acquired during World War II. Six paintings that had been owned by Gottlieb and Mathilde Kraus had been recovered, they learned.

“All of a sudden, paintings that had been part of the ‘mythology’ of the family are alive and there’s hope. There’s a chance,” Graykowski recalls feeling back then.

Figuring there must be more, the family reached out in 2009 to a different organization, the London-based Commission for Looted Art in Europe, for help. Sure enough, after years of research, a seventh painting was confirmed: the “View of a Dutch Square.” But the search for that painting would raise even bigger questions that, even as Graykowski takes ownership of the work of art, remain to be fully answered.

The Looting Begins

Gottlieb and Mathilde Kraus once owned so many paintings — more than 160 — that, in 1923, their apartment had been opened to the public as a museum. But after Austria became part of Nazi Germany in 1938, a union known as the Anschluss, the Kraus family fled, leaving everything behind. Everything included the paintings, one of which was “View of a Dutch Square.” They would ultimately end up in Washington, D.C.; meanwhile, the Gestapo inventoried their apartment in October of 1940, and the art was stored with a shipping company in Vienna before being officially confiscated the following June.

About six months later, 12 of the family’s paintings were photographed for consideration for Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler’s planned museum in Linz, the Austrian city where he spent part of his childhood. But the painting “View of a Dutch Square” wasn’t bound for a museum. Rather, sales records show that it was purchased in July 1942 for about $1,000 Reichsmarks by Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s photographer.

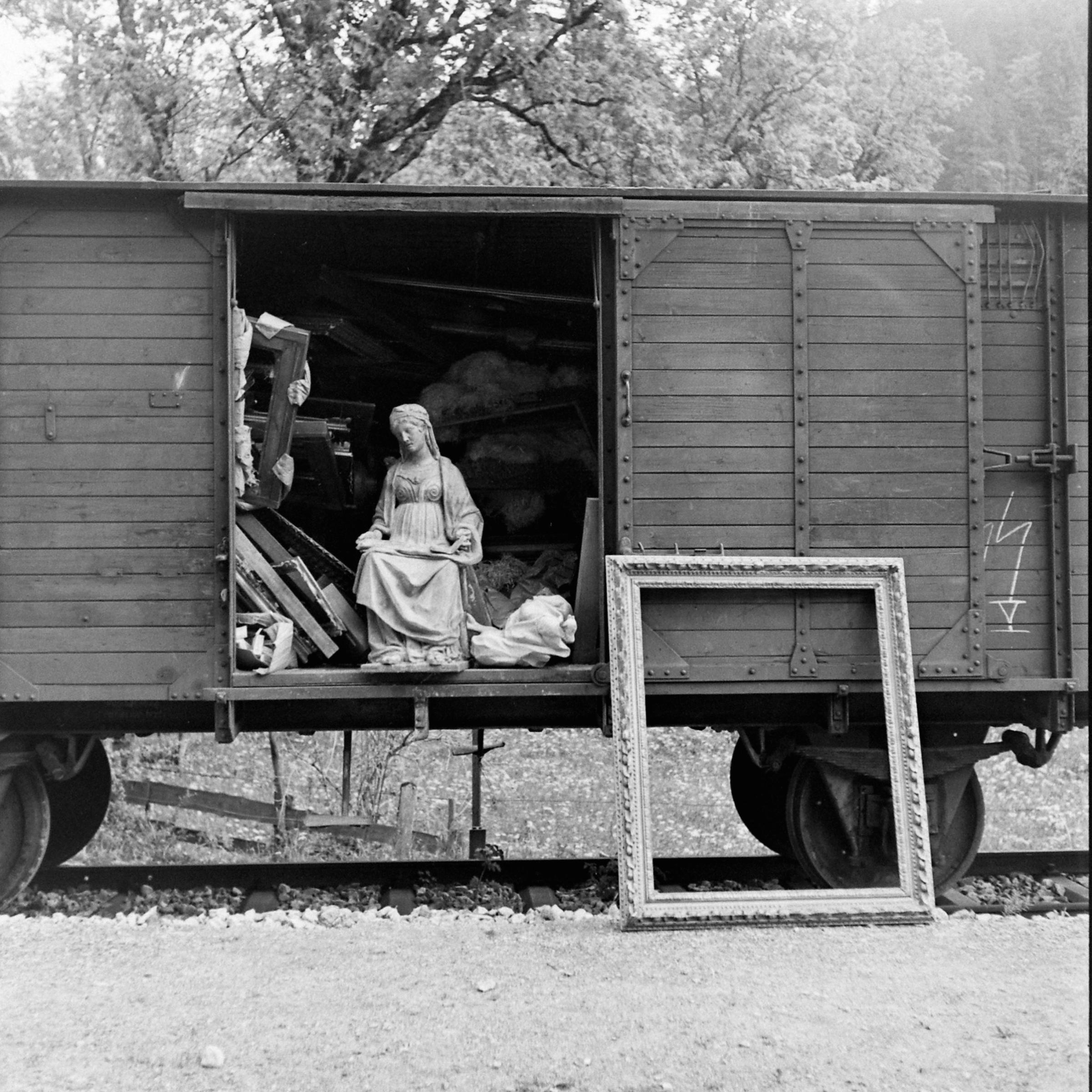

The painting was photographed again after the Allied officers found the Hoffmann collection in May 1945, and sent it to be inventoried at the Munich Central Collecting Point in Bavaria, one of the biggest collecting points set up by the “Monuments Men,” a special Allied unit of art experts who sorted through art confiscated during the war.

“Between August 1945 and May 1951, the Munich Central Collecting Point returned 463,000 paintings to the countries from which they had been taken,” according to the Commission for Looted Art in Europe. But the process didn’t stop there. The U.S. military transferred custodianship of more than 2,500 works of art from the collections of various Nazi leaders and organizations to Bavaria by the early 1950s for the purpose of restitution, and about 800 works were transferred to the Bavarian State Paintings Collection between 1953 and 1977.

The works in Hoffmann’s collection, numbering 278, were among those transferred to the Bavarian State. So, when the Commission for Looted Art in Europe identified “View of a Dutch Square” as a work that had belonged to Gottlieb and Mathilde Kraus, they knew where to look for it: the Bavarian State Paintings Collection archives.

When they went to look for it, however, the painting wasn’t there.

Lost and Found

According to documentation received by the Commission in 2011, the Bavarian State Paintings Collection had sold the painting in 1962 for 300 German Deutsche Marks. The buyer? Henriette Hoffmann-von Schirach, Heinrich Hoffmann’s daughter and the wife of Baldur von Schirach, the Hitler Youth leader who became the Nazi governor of Vienna and oversaw the deportation of the city’s Jews. Henriette, it turned out, had requested and was granted several works from her father’s collection. Her motivations for wanting to re-claim the painting are not clear. In fact, she has said that she stood up to Hitler about his persecution of the Jews at his home and was banned from his house.

And yet the next thing known about its whereabouts is that the Xanten cathedral’s building association paid 16,100 German Deutsche Marks (about $9,300 today) for the painting at an auction in Cologne in 1963.

This wasn’t a matter of just one painting. Between 2009 and 2011, the Commission for Looted Art in Europe discovered that Bavaria returned “many” paintings to the families of Nazi officials. Exactly how many remains unknown. “At the very time that the Kraus family and many families who had survived the Holocaust were making claims for that property and being told that no one knew where their property was,” Anne Webber, Founder and Co-Chair of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe, tells TIME, “their art was being handed back to the families of these Nazi war criminals.”

In 2011, Graykowski made an official claim on the painting. Five years later, the Commission — frustrated, Webber says, by the difficulty of getting official answers on the “return sales” — went public with the news, which was first reported by Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of the largest daily newspapers in Germany. (The Bavarian State Ministry for Education, Culture, Science and Arts and a descendant of Henriette Hoffmann-von Schirach did not return requests for comment, though in the past Bavarian officials have disagreed with suggestions that the state is not fully cooperating with restitution efforts.) Ronald Lauder, President of the World Jewish Congress, said at the time that the research was “absolutely shocking” and that “If the allegations prove to be as severe as presented, it is one of the most scandalous incidents related to the subject to date.” The German Lost Art Foundation, which receives funding from the German government, has a database that lists more than 70 works of art that were in the Bavarian State Paintings Collection that were returned to families of top Nazi leaders, including six paintings to the family of Heinrich Hoffmann.

After a Bavarian Parliament committee called for a full report on artworks Bavaria may have sold back to Nazi families, a report published in October 2016 by the office of the Bavarian Culture Minister explained that provenance research had been going on since 2012 and that, as of July 2016, a little less than half of the 890 artworks transferred to Bavarian State Paintings had been researched. Of those, a little more than half had been marked as “under suspicion of having been looted.”

The German Lost Art Foundation says it has helped the von Schirach family trace Henriette von Schirach’s efforts to regain her father’s collection after the war, and found that she got 118 objects back by presenting sales records for them. Of those, 92 were simply given back to her, and 26 she bought back. “Most of the cultural objects she resold later, in some cases with a large profit margin,” the organization told TIME in a Mar. 21 statement. A full report on the findings, funded by the family, is due this spring.

Victims of Nazi Theft Find Hope

Awareness of the fact that Nazis stole art from Jewish families is high these days, thanks to Hollywood movies and headline-worthy finds, but the restitution process remains long and complicated. After an initial burst of returns around the time of the end of the war, media attention faded as many survivors made an effort to put the war behind them, says Lynn H. Nicholas, author of The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. With the Cold War shifting focus away from Germany toward Russia, and few global governments willing to make a big fuss over privately-owned art, the process essentially paused.

An estimated 600,000 paintings are believed to have been stolen during the war and 100,000 remain missing, Stuart Eizenstat, an adviser to the U.S. Department of State on restitution issues, said recently.

Several factors came together in the 1990s that reinvigorated the efforts to return Nazi-looted art, from the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II to the scandal over whether Swiss banks profited off Nazi-looted gold. Critically, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany led to the opening up of intelligence records that hadn’t been previously available for other restitution issues.

In 1998, 44 nations agreed to the non-binding Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art (more commonly known as the Washington Principles), vowing to identify artworks that might be looted, to publish lists so that families could recover them and to work toward “just and fair solutions.” A year later, Anne Webber, a British filmmaker who’d made a documentary about looted art, founded the non-profit organization Commission for Looted Art in Europe, as a clearinghouse for information on the topic and home to a team of investigators who could help families negotiate restitution settlements. Since its establishment 20 years ago, the organization has recovered more than 3,500 objects on behalf of families.

The Internet has also helped possible heirs find resources more easily, and has created more opportunities for these connections to be made. For example, the genealogy website MyHeritage told TIME that last fall it notified eight families that they are descendants of original owners of works of art that appear on a Dutch Museum Associations list of about 170 artworks considered “likely to have been stolen, confiscated or sold under duress between 1933 and 1945.” The families had no idea about the lists, and some didn’t know they were even descendants of the owners of these works of art.

In the case of the painting of the Xanten cathedral, Gestapo account books, combined with sales records for and photographs of the painting, proved that the artwork belonged to Graykowski’s family.

But because the Washington Principles are not legally binding, the laws about claiming art varies by country. Hans-Wilhelm Barking, chairman of the Dombauverein Xanten, the non-profit society for the Xanten cathedral’s preservation, made that point in a joint press release published Thursday with the Commission for Looted Art, noting his organization was returning the painting voluntarily: “I ask for your understanding that I have certain difficulties to speak of a ‘return’ of the painting. This term may imply that the [cathedral society] may not have acquired the painting lawfully and may not have become the lawful owner. I therefore prefer the term ‘surrender,’ which is done voluntarily in recognition of the Nazi injustice.”

The Painting Returned, Now What?

Graykowski would agree that the subject of Nazi-looted art is not really a matter of what’s legal. Restitution is about what’s moral, he says. “This was my family’s property,” he says. “It was stolen. I want it back. A very simple construct.”

He believes the process would go faster if governments paid private individuals or organizations for returning looted art in their possession. But it isn’t really about the money, either. A 2017 appraisal showed the painting of the Dutch square was worth about $5,000, but he says he’s been looking into bringing things full circle by donating it to the Jewish museum in Vienna.

And now it’s on to finding the other 160 paintings.

“I told my son, who is 29,” he says, “you’ll have to continue this.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com