In 1909, the federal government brought charges against the country’s best known soft-drink manufacturer, charging it with false advertising and for quietly loading its bottles with a risky stimulant. The case — named for a seizure of specially prepared syrup — was formally titled United States vs. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca Cola.

Two years later, in the spring of 1911, the trial commenced in Chattanooga, Tenn. Many had expected its focus to be on the illegal drug cocaine, which in the 19th century had been a celebrated part of the company’s formula, highlighted in its famously pep-you-up advertising schemes.

But Coca-Cola, under legal and consumer pressure, had removed cocaine from the ingredients almost a decade earlier. The stimulant at the heart of the government’s accusations — to the surprise and dismay of coffee-swilling journalists covering the trial — was the popular but poorly understood plant alkaloid caffeine.

And as it would turn out, caffeine would not only be the star of the three-week proceeding — its reputation would also be burnished by the scientific work done by expert witnesses, notably the meticulous research of New York psychologist Harry Hollingworth. His carefully measured results told reporters — and their readers nationwide — that a morning cup of coffee (or two or more) was likely to make them more coordinated and smarter on a daily basis. “Gradual rise of spirits,” reported one of Hollingworth’s test subjects after a jolt of caffeine. “Then a period of exuberance.”

As a result, the Coca-Cola trial of 1911 helped establish caffeine as the country’s pick-me-up of choice. Not that it was planned that way.

The chief chemist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, then responsible for the safety of all American food and drink, was known to be caffeine-hostile. Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley had earlier declared that soft drinks containing the compound were “habit-forming and nerve-racking.”

Wiley and the head of his pharmaceutical division, Lyman Kebler, were focused on the “medicated” soft drinks sold to the public at that time. Many — with names like Kola-Kok and Koke — still slipped some cocaine into the mix. Others like, Seven-Up, contained lithium, and others, like Coca-Cola in the early 20th century, contained a jolting level of caffeine (a glass then was comparable to a can of Red Bull today) and were often cheerfully marketed to children. Kebler, during one of his investigative trips, was horrified to find children as young as four slugging down the stimulant-rich soft drink. He drafted a report on the beverages with the provocative title: “Habit-Forming Agents: Their Indiscriminate Sale and Use a Menace to the Public Welfare.”

Wiley began pushing the agriculture department to make a test case of Coca-Cola, the country’s largest soft drink manufacturer. The business-friendly Secretary of Agriculture, James Wilson, stalled him off until an investigative journalist from Atlanta threatened to expose the government’s cozy relationship with the soft drink industry. Two weeks after meeting with Fred Seeley, of the Atlanta Georgian, in the fall of 1909, Wilson authorized the seizure of Coca-Cola syrup bound for soda fountains. “It is remarkable,” Wiley wrote sarcastically, “what fear of publicity will do.” But after two years of building a case, he hoped that the 1911 trial would put an end to this nonsense.

The government lined up a formidable array of more than 20 witnesses critical of the soft drink company and its product. These included toxicologists who testified that the drink caused “reflex irritability,” behavioral scientists who warned that it was addictive — noting that the drink was nicknamed “Dope” and “Coke” — and consumers who described themselves as hooked on the drink. The testimony finished with Kebler, who declared that “caffeine is a drug having poisonous tendency.”

Coca-Cola naturally disputed all of this. Vice president Charles Howard Candler emphasized that “The company has never advertised or sold Coca-Cola under the names ‘Dope’ or ‘Coke” or any other drug-related terms.” (It did not trademark the use of “Coke” until 1945.) It also provided an assortment of happy soda drinks and a roster of toxicologists who countered the government testimony by declaring caffeine safe. “I know of no case of caffeine in any quantity causing death,” stated John Marshall, of the University of Pennsylvania, famed as one of the country’s leading toxicologists.

But it was Harry Hollingworth’s testimony that gained most attention. Coca-Cola had realized that there was no serious human data on caffeine effects. The company hired Hollingworth, a young Columbia-trained psychologist, to do that work in short order. Hollingworth, then a lecturer at Barnard College and later the head of the psychology department there, signed on only on the condition that the company agreed he could publish the results whether or not they were favorable.

His 40-day study, run with the help of his wife Leta Stetter Hollingworth (who would later become acclaimed for her research into gifted children), was meticulous in design. He recruited 16 participants, ten men and six women, all tested to make sure they were in good health. The subjects received daily capsules that contained a placebo, caffeine or Coca-Cola syrup in a range of doses. The study was double blind, meaning that neither the test subjects nor the scientists knew who had received what until after the tests were completed.

The Hollingworths tested for speed of reaction, steadiness, coordination and mental acuity. Examples of the latter included color recognition, word-opposite tests, math calculations and speed of discrimination. By the time they were done, Hollingworth had 64,000 data points, which he presented to the slightly stunned Tennessee jury through a series of graphs and charts.

“His testimony was by far the most interesting and technical of any yet introduced,” The Chattanooga Daily Times reported. “Cross-examination failed to shake any of his deductions.” The scientist reported on “an increased capacity” clearly related to caffeine. It was, Hollingworth said, rapidly and temporarily uplifting, and its predominant effect seemed to be quicker mental reactions and finer motor coordination.

Still, his work did not win the day for Coca-Cola. Instead, the trial ended a few days later, just as the government was planning to call rebuttal witnesses, when the judge dismissed the case on a technicality — a new argument from the company that caffeine was a naturally occurring ingredient, rather than an additive as USDA claimed, and therefore could not be challenged under federal law.

The government would fight that decision even after Wiley’s retirement the following year and, in 1916, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the finding and declared caffeine to be an additive under the law. Shortly later, Coca-Cola settled the case by agreeing to pay all court costs — and by cutting the amount of caffeine in its soft-drink by half.

A hundred years later, we’re still studying caffeine and it’s clear that too much does indeed pose some jittery health effects and that an extremely high dose (comparable to about 100 cups of coffee) can be lethal. But the balance of studies continues to suggest that moderate use has genuine positive effects — as Hollingworth reported in 1911, and to the undoubted relief of coffee drinkers everywhere.

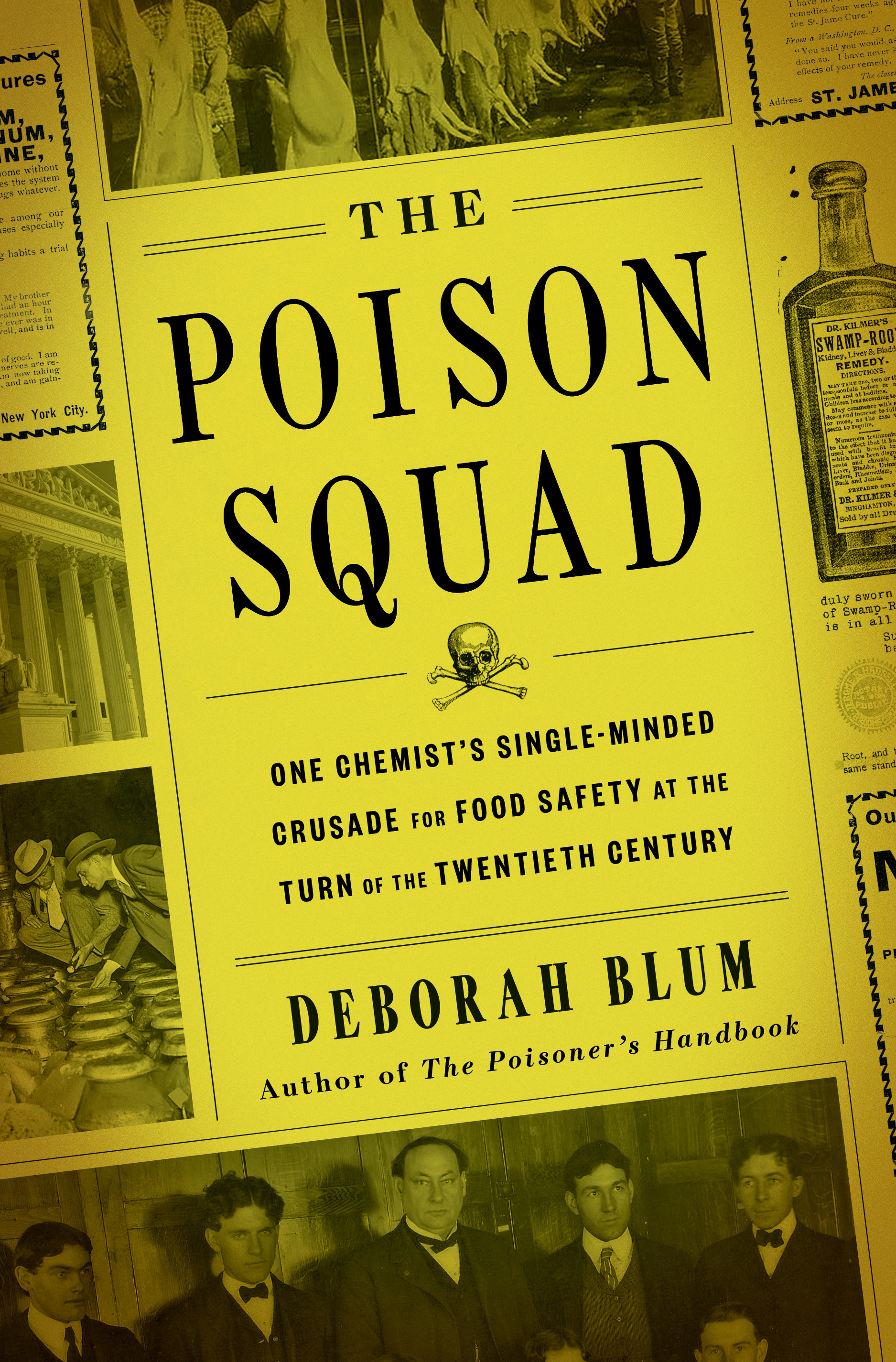

Adapted from THE POISON SQUAD by Deborah Blum, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Deborah Blum.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com