World health leaders met on Friday to discuss the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and concluded that for the time being, while the outbreak is serious, it is not a public health emergency of international concern.

The director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, convened the meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee in Geneva. Tedros, as he prefers to be called, previously visited an affected area of the country and said he’s impressed by the local response. “We were encouraged by what we have seen despite the challenge,” he told reporters on Friday. “There’s strong coordination between government and other partners.”

Dr. Robert Steffen, chairman of WHO’s emergency committee, announced the WHO’s decision. “It was the view of the committee that the conditions for a public health emergency of international concern have not been met,” he told reporters.

So far, 14 cases in DRC have been confirmed by laboratory testing, according to the WHO. While most of the cases were in remote areas, one of the people tested positive in Mbandaka, a densely populated city of nearly 1.2 million. There are also 21 other probable cases and 10 suspected cases. Three health workers are among the reported cases. The WHO has requested $26 million to aid in the response.

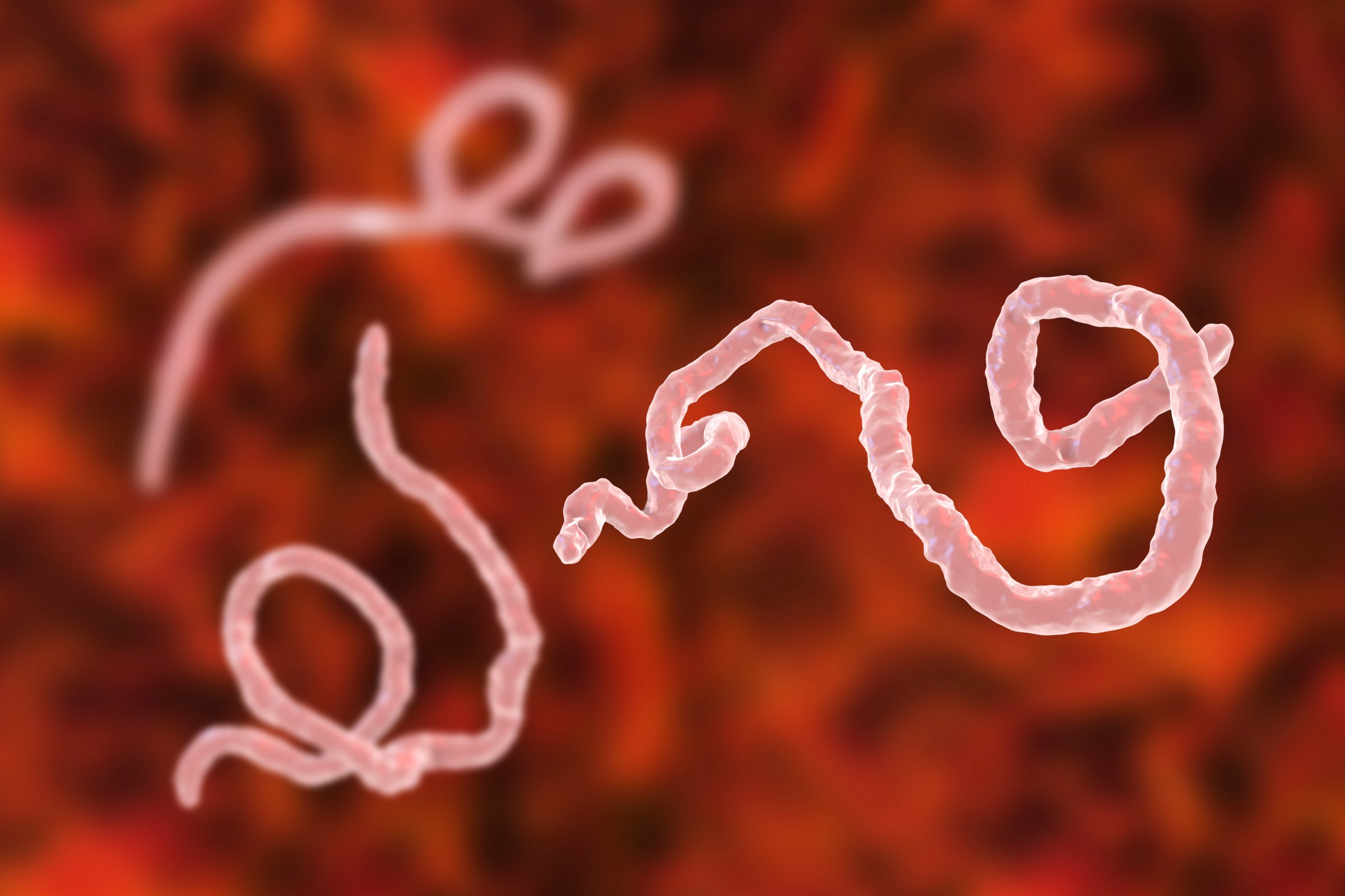

Ebola is a virus that spreads through direct contact with the bodily fluids of someone who is infected with the virus or has died from it. It can also spread from from the bodily fluids of animals to humans. There’s currently no cure, but there is an experimental vaccine.

MORE: How Ebola Got So Deadly

The locations of the current outbreak are particularly concerning. In the urban area of Mbandaka, the risk of transmission is high. The WHO and other groups maintain that one of best ways to control a virus like Ebola is to identify an individual with the disease, isolate and treat them, and then locate and potentially isolate anyone they came in contact with. In a city of more than one million people, that’s a much more difficult task. There are also challenges in the remote area where other cases have been reported—including that it’s very difficult to access. The 2014 to 2016 Ebola outbreak took place in largely rural areas of Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, and more than 28,600 people were ultimately infected, resulting in 11,310 deaths.

“With the confirmation of a positive case of Ebola in Mbandaka, we are moving to a new phase of the epidemic and we are making every effort to respond quickly and effectively,” the DRC’s minister of health, Dr. Oly Ilunga, said in a tweet on Wednesday.

According to Dr. Pierre Rollin, a medical epidemiologist in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens, it’s unclear exactly where and when this outbreak started, and it’s possible that cases started spreading as far back as January. The CDC has a field office in the DRC with a few members who are providing assistance, and a team of U.S.-based experts are ready to offer support to the country if the WHO requests it. “We have a roster of people ready to deploy,” says Rollin.

The medical humanitarian group, Doctors Without Borders—also known as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)—is currently in the DRC providing care. The group has isolation zones in at least two area hospitals and is setting up more Ebola treatment centers. MSF was one of the first groups to sound the alarm on the 2014 outbreak.

An experimental vaccine by the drug company Merck will also be used on health workers and people who have come in contact with infected individuals starting on Sunday. The WHO has a stockpile of 4,300 doses of the vaccine in Geneva, and there’s another 300,000 doses in the U.S.

The DRC has experienced nine outbreaks of Ebola since the very first outbreak in 1976. Last year, there were eight cases of Ebola reported, and half of the people who were infected died. Bats are considered a top carrier for disease, and experts believe that the large forests in the DRC help make it a reservoir for the virus, thanks to the bat populations that live there.

The WHO says that no international travel or trade restrictions are needed at this time. Airport screenings are beginning in the country, and the WHO says neighboring countries should be vigilant and prepared. The committee will continue to follow the situation, and depending on the spread, the group could reconsider its position on whether the situation constitutes an international emergency.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com