Hawaii’s false ballistic missile alert was the latest reminder of the nuclear threat that North Korea poses to the U.S. amid the rising tensions and war of words between the two nation’s leaders.

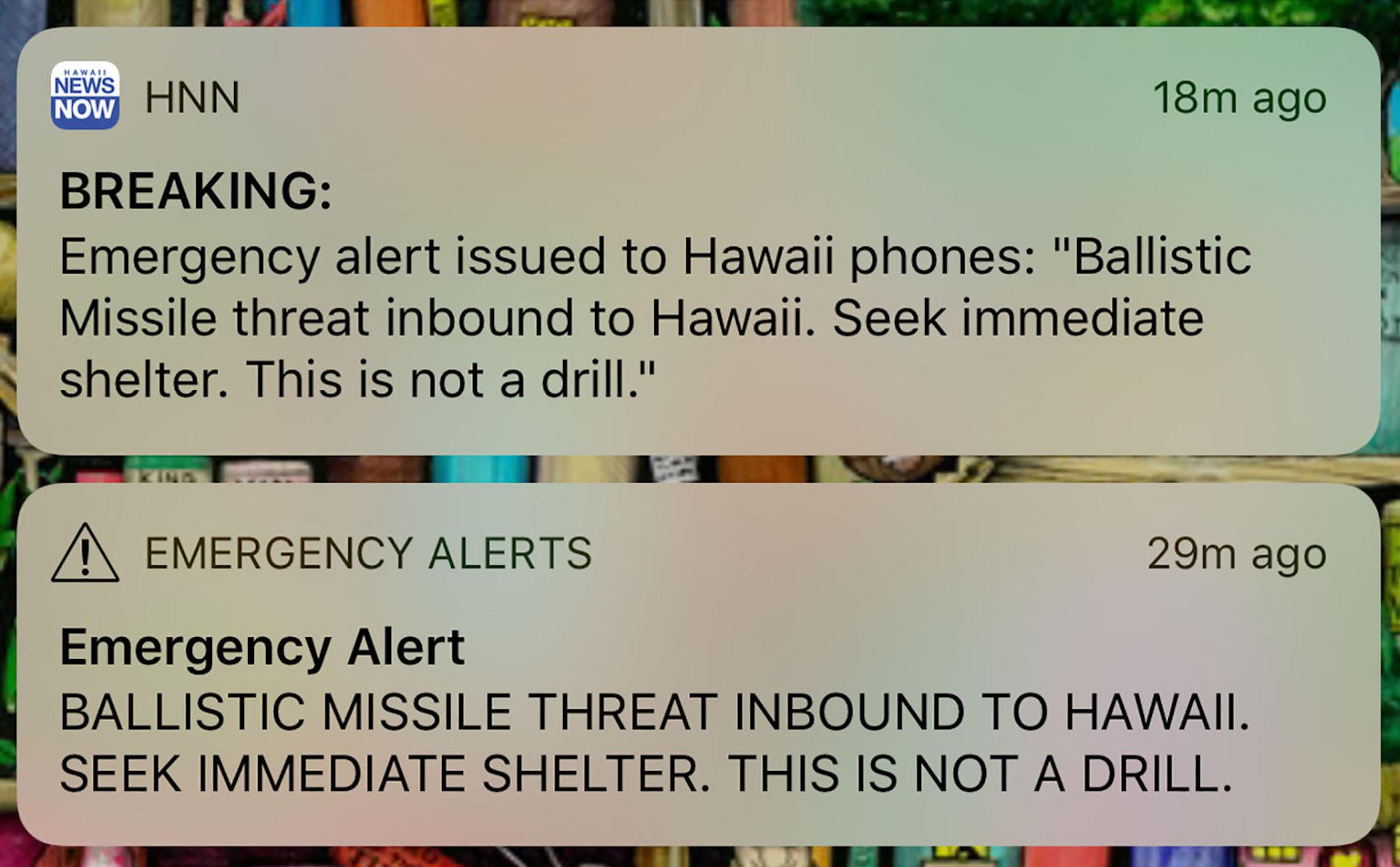

“BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL,” said the emergency system alert pushed to people’s smartphones statewide.

It wasn’t until a second message popped up 38 minutes later that people learned the missile alert was a mistake, later blamed on someone pushing the wrong button. But had the alert been real, a series of high-level assessments and decisions would have been made during that time in quick succession, perhaps with dire consequences.

The U.S. military officers at Pacific Command headquartered at Honolulu were able to immediately determine Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency had made a mistake and publicly delivered messages to that end.

Every moment of every day, the U.S. military and intelligence agencies have satellites in high-Earth orbit scouring the globe for anything amiss. The so-called early warning satellites are designed to identify within seconds the location of the launch site, the missile’s trajectory and its potential target.

A constellation of school bus–sized satellites, known as the Defense Support Program, forms the backbone of the system. The spacecraft are armed with cutting-edge infrared sensors and instruments that operate at wide angles to detect heat signatures from missile plumes as they flash against Earth’s background.

The satellites are sensitive enough to detect a short-range missile’s launch, and are therefore capable of tracking a North Korean ballistic missile as it headed 4,600 miles toward Hawaii.

U.S. radar installations, naval ships, and allies’ detection systems in the region would assist in tracking the weapons’ flight and capturing its electronic emissions. For instance, all North Korean missiles use guidance and tracking systems to help guide it to a target.

A combination of all this intelligence over a period of seconds or minutes would allow the U.S. government to triangulate the point of launch and track the trajectory of the missile, much of it under a method of spy-craft known as measurement and signature intelligence, or MASINT.

The information would be relayed to U.S. Forces Korea, headquartered in Seoul, and U.S. Pacific Command. A decision would be made on whether Americans were at-risk and if the U.S. or its allies should use missile defense systems to attempt a shoot-down. That could take place on the Korean peninsula, where the U.S. recently deployed new systems, or by Japan’s missile defense network, or by American warships carrying interceptors operating in the Pacific Ocean.

Adm. Harry Harris, head of Pacific Command, said in April that the missile defense systems in Hawaii were adequate for now but suggested considering stationing new interceptors and radar to knock out waves of incoming North Korean missiles.

“I believe that our ballistic missile architecture is sufficient to protect Hawaii today, but it can be overwhelmed,” Harris told Congress.

If a missile attack were determined to be a nuclear strike, a decision on a counter-strike would have to be made by President Donald Trump. The order to strike, which only the president can make, would be relayed to U.S. military officers in command of the nation’s intercontinental ballistic missiles, nuclear submarines or heavy bombers.

As tensions continue to rise with North Korea, states like Hawaii and others governments are re-evaluating how well prepared they are in the event of a nuclear strike.

The messaging from civil defense agencies — remember Duck and Cover? — that had been fine-tuned during the Cold War has melted away in the intervening years. The federal government and law enforcement is more prepared for the aftermath of a terror attack than a missile attack — let alone one involving a nuclear detonation.

The false missile alert in Hawaii is all but certain to jolt many state and local governments to reassess their processes.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to W.J. Hennigan at william.hennigan@time.com