Babies born in America are less likely to reach their first birthday than babies born in other wealthy countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a new study found. While infant mortality rates have declined across the OECD since 1960, including in America, the U.S. has failed to keep pace with its high-income peers, according to a report published in the journal Health Affairs.

Compared to 19 similar OECD countries, U.S. babies were three times more likely to die from extreme immaturity and 2.3 times more likely to experience sudden infant death syndrome between 2001 and 2010, the most recent years for which comparable data is available across all the countries. If the U.S. had kept pace with the OECD’s overall decline in infant mortality since 1960, that would have resulted in about 300,000 fewer infant deaths in America over the course of 50 years, the report found.

The reasons the U.S. has fallen behind include higher poverty rates relative to other developed countries and a relatively weak social safety net, says lead author Ashish Thakrar, medical resident at the Johns Hopkins Hospital and Health System.

“The poorer children are, the worse their health outcomes are,” says Thakrar, whose team found that poverty among U.S. children has been higher than in the 19 comparable OECD countries since the mid 1980s.

Premature delivery and low birthweight have been consistently associated with poverty, which affects over 20% of U.S. children, the second highest percent among 35 developed nations, according to a 2013 United Nations Children’s Fund report.

Thakrar’s team used membership in the OECD as a proxy for similar nations to the U.S., and narrowed the group to 19 members for which 50 years of high-quality data was available, known as the OECD19.

Thakrar’s research supports a 2013 National Academy of Medicine report, which found Americans’ health has fallen behind that of other high-income countries. “Their big conclusion is that the gap stems from risky health behavior and a fragmented health system,” Thakrar says.

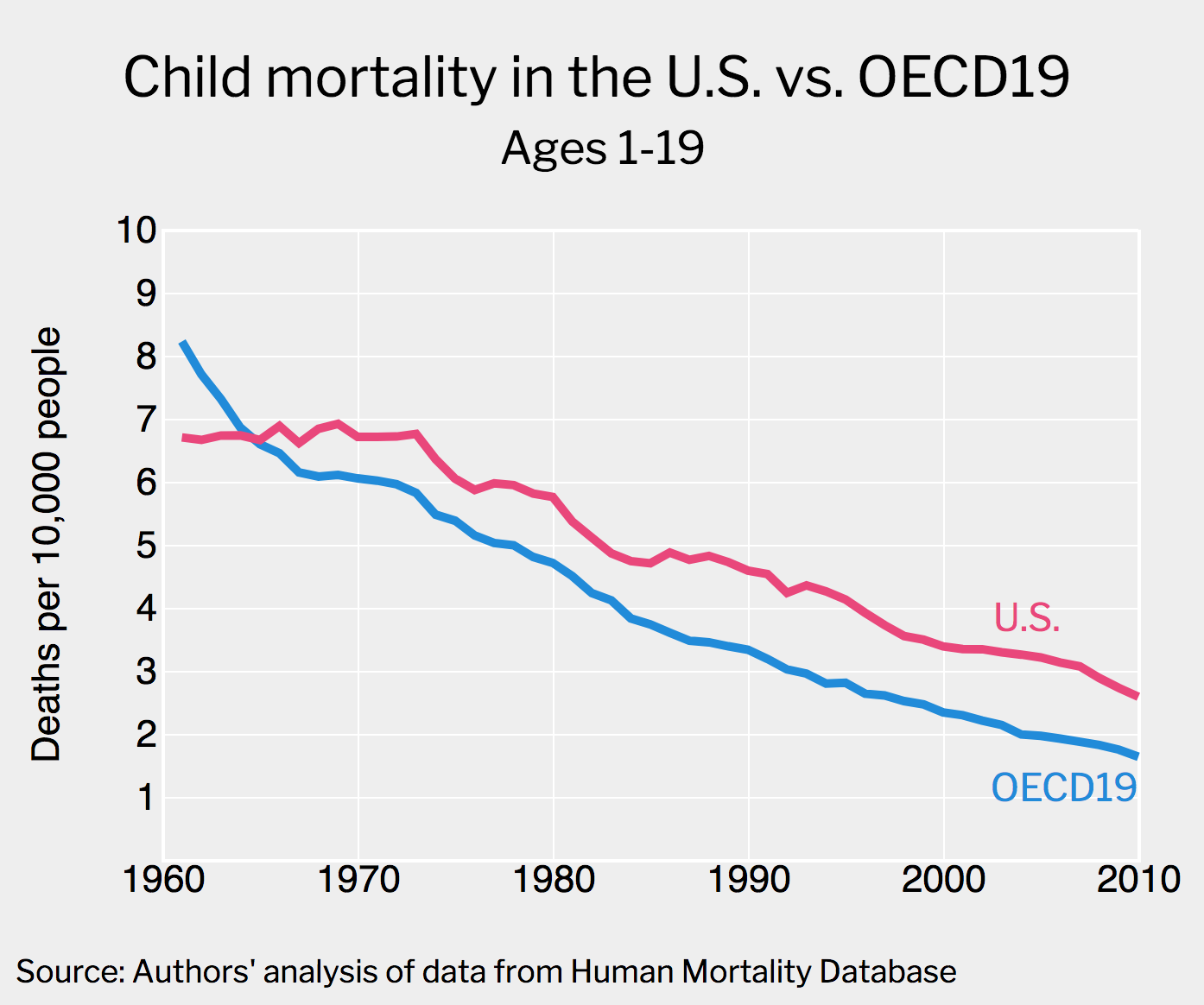

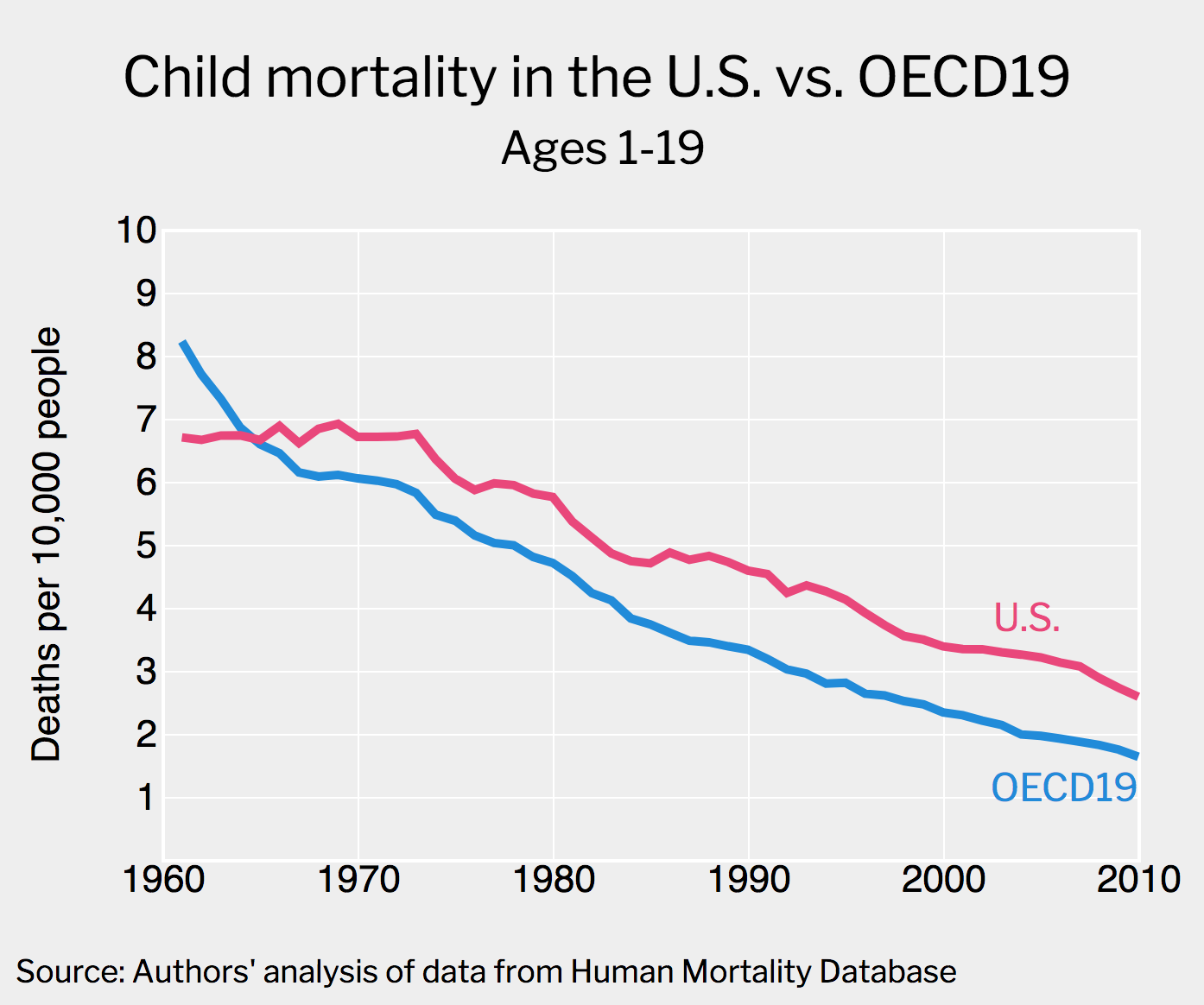

Child mortality in the U.S., defined as deaths of children age 1 to 19, has likewise seen slower declines than in other developed nations. The numbers in the U.S. are partly driven by gun deaths. From 2001 to 2010, 15-to-19-year-olds were 82 times more likely to die from gun violence in the U.S. than in other wealthy countries.

Thakrar also attributes the higher U.S. child and infant mortality rates to a lack of preventative care. While the U.S. spends the most on health care per capita compared to OECD nations, some of them have stronger public benefits programs, Thakrar says. “We spend more on health care that’s taking care of children that are already sick,” he says. “But we spend far less money on welfare programs to keep children from becoming sick, and on keeping them safe from injuries.”

Methodology

Membership in the OECD was used as a proxy for similar nations to the U.S. The group was narrowed to OECD members with 50 years of high-quality data, minus the U.S. It includes: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com