The annual observance of Giving Tuesday — which raises awareness about charity on the Tuesday after Thanksgiving, and which led to more than $168 million in charitable donations in 2016 — is a recent innovation. But, while crowd-funding sites and social networks have created new opportunities to spread the word more quickly, such campaigns carry on a tradition that, in the U.S., dates back about a century.

Historically, though wealthy people had participated in philanthropy of many kinds, average citizens participated in charity primarily through their churches, explains Dwight Burlingame, editor of Philanthropy in America: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopaedia. “That’s how people took care of themselves in the community,” he says. At the end of the 18th century and in the early 19th century, in the nation’s early days, that function was particularly pronounced. Then, especially between the 1830s and 1850s, voluntary non-profit associations geared towards social and political change, outside the church, formed.

“Alexis de Tocqueville commented upon these private endeavors as a uniquely American phenomenon during his visit to the U.S. in the 1830s,” says Mark McGarvie, professor of law at William & Mary Law School and author of Law and Religion in American History. “Collectively referred to as forming the ‘Benevolent Empire,’ they became the first modern American philanthropies. Concerned Americans from across the nation donated time and money to causes dedicated to undoing the secular individualism formed in the founding era.”

Benjamin Soskis, a research associate in the Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy at the Urban Institute, adds that the mentality of that time “got Americans thinking about their responsibilities not just locally but also nationally, so their scope of giving starts to expand.”

In the late 19th century and turn of the 20th century, as cities grew and more people moved to urban areas for factory jobs and immigration, the character of American philanthropy evolved too. Voluntary associations sprang up to help new foreign residents assimilate to the American way of life. Business managers with their own motivations also participated in charity. The YMCA, for example, Burlingame says, got much of its funding from from businesses looking for safe housing for their workers so they wouldn’t get drunk at night — and so that they would be able to report for work in the morning.

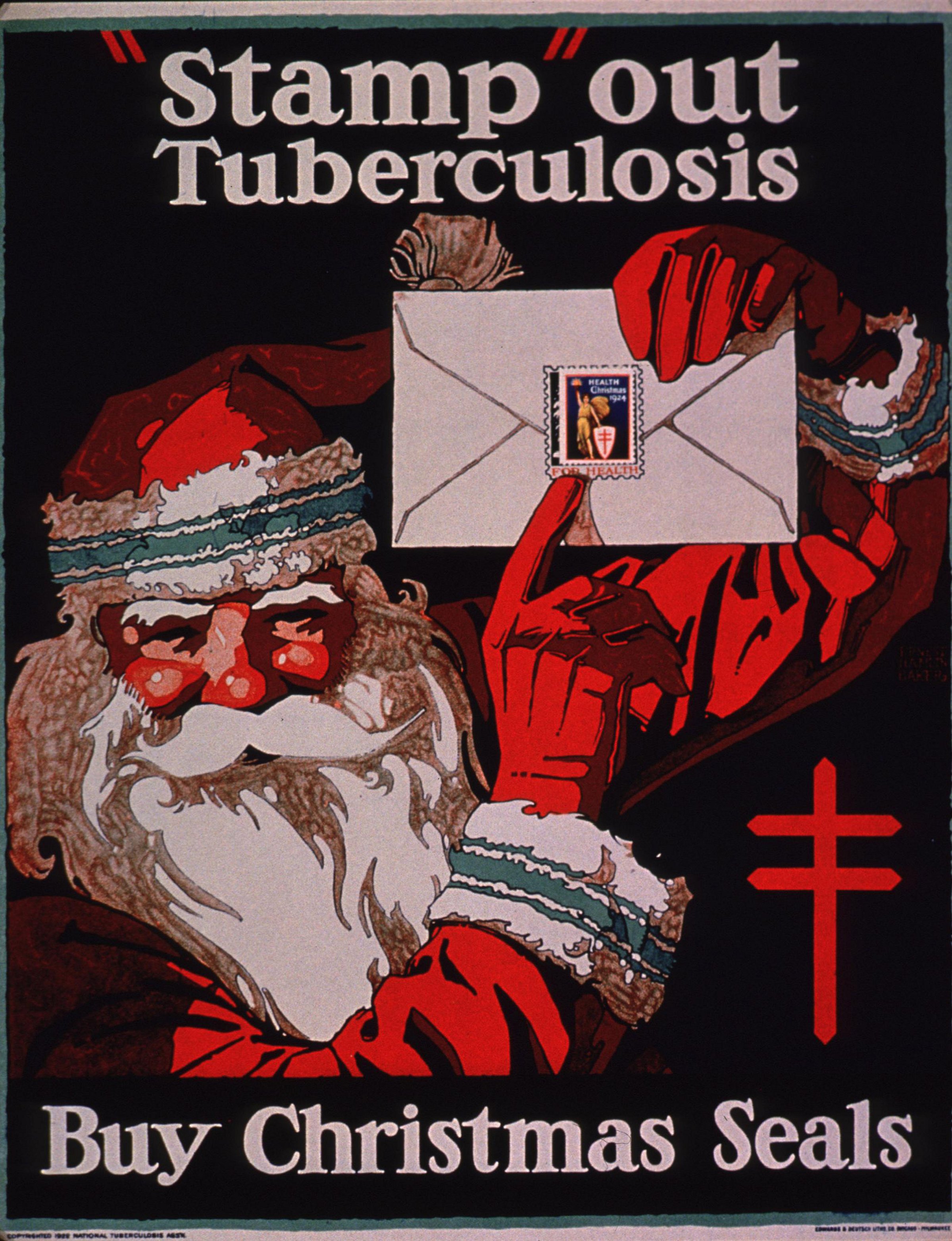

Yet more people in one place meant more people crammed into tight spaces. Airborne diseases like tuberculosis (TB) created a public health crisis, with some estimates claiming that 450 Americans died of TB every day during that period around the turn of the century.

The epidemic hit close to home for Jacob Riis, chronicler of urban slum conditions, whose six brothers died of the disease — and in response he helped create the impetus for a campaign that looks remarkably similar to today’s mass-giving drives.

In 1907, Riis wrote an article for Outlook magazine, describing a letter he received from Denmark that had a seal next to a stamp on the envelope, the proceeds from which went to efforts to take care of children with TB. He called for a U.S. version of the clever fundraising campaign, “for the purpose of rousing up and educating the people on this most important matter,” and urged Americans not to wait for some Gilded Age financier to make a donation. Together, the people could prove that, though they may not have much individually, they could collectively make a difference, he argued: “No millionaire is wanted to do it. It were far better done by the people themselves, for only in doing it so will they learn that which is of more value than preaching and doctoring—namely, how to help themselves.”

His call was heeded by Emily Bissell, a member of the magazine’s editorial board and a secretary of the Delaware Red Cross. In 1908, the Red Cross sold “Christmas seals” to benefit the National Tuberculosis Association (whose symbol is the Lorraine cross on the bottom right corner of the featured image above). The effort raised $135,000 that year and $1 million by 1916 — nearly $24 million in today’s dollars. The campaign appeared to be helping: the year 1932 saw the lowest TB death rate then on record in 59 American cities, from an average of 174.4 deaths per 100,000 in 1910 to 63.2 in 1931, and 56.3 in 1932. And when news of the vaccine was announced in Dec. 1929, the press push was timed to “stimulate Seals sale,” as TIME reported.

And mass giving was directed towards other causes too. A single week-long call for donations in June 1917 raised about $115 million for the World War I war effort, according to The American Red Cross: A History by Foster Rhea Dulles.

However, what Soskis calls “the heyday of mass giving” came much later, with the rise of the middle class in the post-war period. In the 1950s and ’60s, increased disposable income led to increased giving — though the social movements of the time also made charity more of a political decision. “Giving became a way to express political values not just broad moral values,” as Soskis puts it. “In turn, the percentage of giving that goes to religious institutions declines from more half in the late ’70s and early ’80s to around a third now.” (Though religion remains the top destination for giving, that share has grown smaller as people have tended to spread out their donation dollars between a wider number of causes.)

In the 21st century, philanthropy in the U.S. is changing yet again.

Philanthropy coming from new class of Silicon Valley elites “dwarfs anything that ever happened before,” says Soskis, which means that select individuals can have proportionally even more of an impact than mass-giving campaigns. “Mass giving,” he says, “is dependent on an egalitarian wealth distribution.”

That said, there is some evidence that individual giving may be on the rise, according to Giving USA’s annual report on philanthropy in 2016, which showed giving by individuals rose 4 percent.

“In 2016, we saw something of a democratization of philanthropy,” said Patrick M. Rooney, associate dean for academic affairs and research at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University, in a statement on the report. “The strong growth in individual giving may be less attributable to the largest of the large gifts, which were not as robust as we have seen in some prior years, suggesting that more of that growth in 2016 may have come from giving by donors among the general population compared to recent years.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com