Over the roar of the guitar, the gunfire erupted. At first the country-music fans at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas thought the loudspeakers were malfunctioning or that the pyrotechnics had gone awry. But as the bodies crumpled, the crowd began to grasp the horror that was unfolding.

The rapid pop pop pop exploded around Doris Huser, 29. She and her 8-year-old daughter had been in the bathroom, but when the shooting began, they pushed back into the crowd, toward the sound of the bullets, in search of Huser’s 5-year-old son and her developmentally disabled sister. They could feel the bullets pinging off the concession stands, ricocheting off the pavement around them. About 50 yards away, Tyler Reeve, a 36-year-old country artist and songwriter, dove into a production trailer with five friends and lay on the floor as hundreds of rounds rang out. “It was like a war zone,” he says. Piles of bodies were everywhere. Blood collected in pools. Everyone was screaming. Melissa Bayer, who had just left a nearby Hooters, witnessed the mayhem from a hundred yards away. This a mass shooting, she thought. This is what it looks like.

If their initial reaction to the opening salvos at 10:08 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 1 had been confusion, the 22,000 concertgoers spent the next nine to 11 minutes of protracted gunfire trapped in a nightmare that, for so many Americans, has somehow become grimly familiar: the shaky cell-phone footage of carnage, the photographs of innocent victims in the newspaper, the profiles of horror and heroism. There was the 48-year-old woman who heard her husband, a father of four, collapse on the asphalt next to her, and the young man who sprinted alongside his eight-months’-pregnant wife, running for their lives. There was the 30-year-old woman who lay on top of her 21-year-old brother to protect him from the hail of bullets, “because he has big goals in life.”

But when the shooting ended, this terror would be in a class apart. Stephen Paddock, 64, who smashed the windows of his 32nd-floor Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino suite and trained an assault-style semiautomatic weapon on the helpless souls four football fields away, broke another dismal record for American murder. At least 58 dead, at least 527 wounded, by a man who, for no immediately discernible reason, lugged an arsenal of 23 weapons into his high-roller suite and then rained of hundreds upon hundreds of bullets into a tightly packed crowd. Twelve of his high-powered rifles were modified with legal parts that made them function like automatic weapons, capable of unleashing nine rounds per second, a rate of fire rarely seen off the field of war. The military-grade rounds, fired from what seemed to be large-capacity magazines, produced so much gun smoke they set off the detectors in Paddock’s suite.

Year after year, mass shootings have broken record after record for casualties. From a university in Virginia to a gay dance club in Orlando, the body count has increased, creating an image of an unstoppable national slaughter. High-profile battles over background checks and gun-show loopholes have stalled on Capitol Hill, even as gun-rights advocates introduce new provisions to weaken the existing constraints.

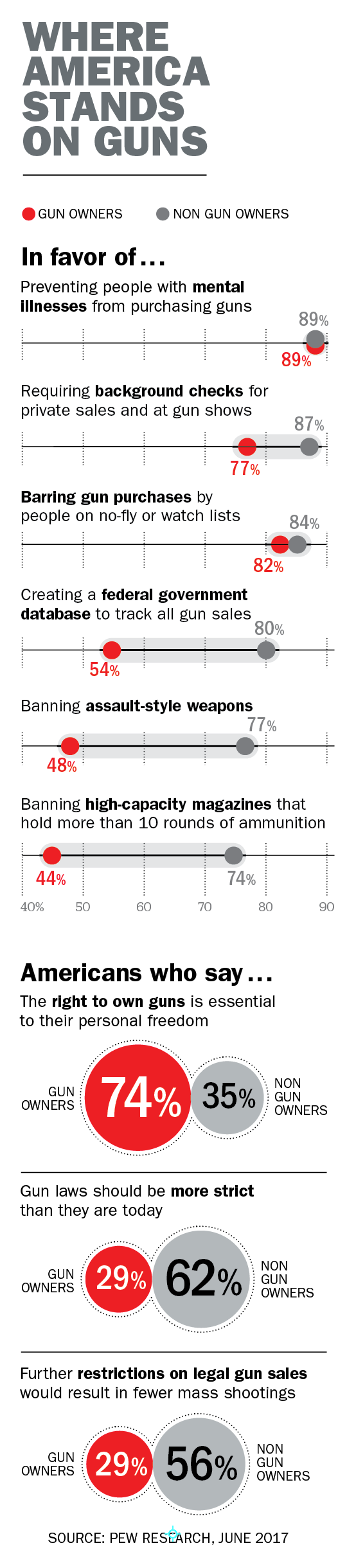

But it’s not an unfixable problem. New laws could at least limit the carnage when a murderer opens up on a crowd. We have decided that grenade launchers should not be widely available; why should we not say the same for devices that allow bullets to be fired at a rate of more than 400 rounds per minute? Nor is the political divide as unbridgeable as it appears. The National Rifle Association (NRA) and its allies are not all-powerful: the lobby relies on the intensity of a small cadre of fervent supporters, and it does lose races, such as last year’s campaign to replace Senator Harry Reid of Nevada. The majority of gun owners believe in some form of regulation, and several Republican Senators have suggested they are open to compromise.

The challenge in bringing change is that the debate over gun rights isn’t really about guns at all. It’s about what they represent: cherished freedoms, a reverence for independence. The guns are a rejection of political correctness that creeps into everything. Even the most incremental move to constrain deadly weaponry seems to many Americans to cut against their rights. In the blood-soaked scene on the Vegas Strip, those deeply held beliefs collide with our collective horror. The question now, as the victims try to make sense of slaughter on a military scale, is where do we draw the line?

If that is a political question, it is has proven a confounding one. There are an estimated 265 million guns in the U.S., according to one study from Harvard and Northeastern universities–greater than the total number of votes cast in last year’s presidential election. They are owned by 30% of the adult population. That’s not a constituency to be dismissed. But not all gun owners are against all forms of gun control. A Quinnipiac University poll in June 2017 showed 94% of voters support background checks for all gun buyers–including 93% of Republicans. The same poll found that a majority, 57%, believed guns are too easy to buy, and only 35% thought more people carrying guns would make Americans safer. A Pew survey of gun owners found that almost 30% of them support stricter gun laws. “There’s a complete disconnect,” said Senator Amy Klobuchar, a Minnesota Democrat.

So why are measures like closing background-check loopholes and limiting high-capacity magazines not already law? It’s partly because a small but intense group of gun-rights advocates oppose them. A paltry 3% of households own half of all of the guns in America, and they vote. It is they who argue most vocally that if existing gun-control laws can’t stop mass shootings, why would new laws be any better? Change might make people feel good, this argument goes, but it wouldn’t protect Americans. “Short of a total ban on firearms, nothing being suggested would have stopped this kind of shooting,” says Dudley Brown, president of the National Association for Gun Rights, of the Vegas massacre.

In one sense, history supports that argument. In 2004, Bill Clinton’s ban on semiautomatic rifles, known as assault weapons, expired. But rather than spiking back up, the rate of gun homicides continued to drop. From 1993 to 2014, that rate declined from seven firearm-related homicides per 100,000 Americans to half that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gun-rights advocates used that as an example of gun-control laws not working. In truth, Clinton’s “ban” was so full of loopholes no one believed it had been responsible for much of the decline in firearm-related deaths in the first place.

But it is less logic than political fear that has thwarted the passage of even modest gun-control measures. As the NRA and like-minded groups have become expert at harnessing a relatively small group of uncompromising gun-rights advocates, politicians fear being targeted in their next election. The combination of money and motivation has been powerful. So fierce was the NRA’s opposition to Hillary Clinton last year that 1 in 8 ads on the air in Ohio was on guns; that ratio was 1 in 9 in North Carolina. Trump won both states. “The source of the NRA’s power is not simply money,” says Adam Winkler, a law professor at UCLA and author of Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America. “The NRA’s power comes from the ability to swing voters in tight, close elections. There are a lot of single-issue, pro-gun voters out there that listen to the NRA’s recommendation.” And, in the space of gun-rights groups, the NRA is considered one of the more moderate voices.

That power opened the door to expand gun rights on the state level. After 2004, while advocates for limits on guns attempted to fight their way back on a federal assault-weapons bans, gun-rights groups were pushing to unravel restrictions elsewhere. At the state level, concealed-carry laws were loosened or abolished at a rapid clip. Many states started accepting the gun-license standards of their counterparts, often regardless of whether they were more lax than their own. In Nevada, 38% of adults own guns, private gun sales are legal, and there are no state regulations limiting magazine capacity.

Even on the federal level, where there appeared to be a political stalemate, gun-rights advocates found ways to make progress on the margins. In 2010, a gun-parts manufacturer asked the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) for permission to market a “bump stock” that when fitted to a semiautomatic weapon would allow the single-fire device to unleash a constant barrage of bullets. While the sale and ownership of machine guns have been strictly controlled since the 1930s and such weapons are very rare among civilians, the company argued their device would benefit handicapped gun enthusiasts, and the ATF assented.

Right up until Vegas, gun-rights advocates were trying to advance laws loosening gun restrictions through the Republican-led Congress. Buried in the Sportsmen’s Heritage and Recreational Enhancement (SHARE) Act, which was intended to enhance recreation opportunities on federal land, were provisions allowing the purchase and use of “suppressors,” similar to silencers used by the military and the restraints on the regulation of armor piercing bullets.

The Horror in Las Vegas seemed to change nothing at the Capitol. House Speaker Paul Ryan, a Republican, promoted the virtues of mental-health care when he met with reporters Oct. 3. To his left stood Steve Scalise, a member of Ryan’s leadership team, who was back on the job for the first time in months after a disgruntled shooter ambushed congressional Republicans on a softball field in May. In an interview days earlier, Scalise had told 60 Minutes that the attack on him did not diminish his belief in the Second Amendment and credited his security detail with saving his life. “If it’s not a gun, it’ll be a hand grenade, or it will be a knife or an ax,” he said.

Later, on Oct. 3, Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell dodged queries about guns and ended his weekly Q&A with reporters at the Capitol after just three questions. “It’s premature to be discussing legislative solutions, if there are any,” McConnell said. In many corners a sense of hopelessness settled over the post-Vegas debate. “If Sandy Hook didn’t result in legislation that either eliminated or restricted the type of guns that can be sold, or the people to whom they can be sold, nothing will ever change,” says Patrick Dunphy, an attorney who has sued a gun shop. “When you have someone slaughtering kids in a grade school, if that isn’t enough, what is?”

But it’s foolish to say nothing could have diminished the scale of the Vegas massacre. The evening of Oct. 3, law-enforcement officials said that 12 of the 23 weapons in Paddock’s suite were equipped with bump stocks of the kind that had first received government permission for manufacture in 2010. Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein, who has raised the alarm about bump stocks for years, said she planned to revive her ban on such accessories. “This is the least we should do,” the California Democrat said. Her bill, introduced the next day, immediately drew widespread support among Democrats. Republicans kept a skeptical distance, at least at first.

Meanwhile, other Democrats are shooting for symbolic victories. House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi is pushing for a Select Committee on Gun Violence, a move that may leave Republicans red-faced when they oppose it. Others are considering how to wrangle Republicans to join previous attempts to finally fund the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention programs to figure out just how much of a public-health risk guns pose. And those lobbying for tighter controls on guns say they’d rather focus on the big, stalled fights than the ones that might make a difference on the margins. “The instances of gun violence in this country using fully automatic weapons or weapons approximating fully automatic fire are a small minority of the gun violence,” says Billy Rosen, deputy legal director at Everytown for Gun Safety.

Some are hoping for help from an unlikely quarter: President Trump. Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer tried to find some daylight between Trump and the NRA, which spent a record $30 million on his campaign against Hillary Clinton. “Before he was a candidate and marched in lockstep with the NRA,” Schumer said, “Donald Trump expressed very a reasonable position on gun control.”

In a way, Trump does remain the biggest unknown. He became the first President to address the NRA’s convention in 34 years, in April, but in 2000 he wrote, “I support the ban on assault weapons, and I support a slightly longer waiting period to purchase a gun.” And the President does pride himself on being a dealmaker. West Wing aides worried that a single segment on cable television, or a moment in Trump’s visit to Las Vegas on Oct. 4, might provoke an impulsive statement with the power to reshape the gun-rights debate in America. But the president stayed on message when asked about gun control as he visited survivors at University Medical Center in Las Vegas. “We’re not going to talk about that today,” he said.

Former White House strategist Stephen Bannon tried to quash talk of such an unlikely deal telling Axios that the blowback for any Trump surprise on gun control would destroy the President’s governing coalition. Bannon is probably right that Trump won’t flip, because the cornerstone of this debate, after all, isn’t really about guns. It’s about something much more important to Trump’s base: government power vs. individual rights. Many of the most fervent gun-rights advocates are also furious that the Government–Big G–makes them buy health coverage or pay a fine or pay taxes that underwrite large federal programs. To many of those voters, unfettered access to guns is a gesture of protest that mirrors the nation’s anxiety about the next century–one where many Americans may think of their firearms as a defense against change.

But that’s not what Stephen Paddock was about, at least as far as anyone has been able to determine so far. Wealthy and white, he was an accountant and real estate investor with no apparent criminal record and no history of mental illness, according to his family. He lived in a retirement community in Mesquite, Nev., about 90 miles northeast of Las Vegas, so fresh that it appears to have been built yesterday. The manicured golf course at Sun City Mesquite is an oasis of green in the surrounding desert. The parking lot by the rec center is filled with Jeeps and Kias. Neighbors say Paddock–who lived with his girlfriend, a high-limit casino hostess who hailed from the Philippines but had Australian citizenship–mostly kept to himself. According to his younger brother Eric, Paddock liked cruises and Mexican food and taking trips to Vegas to play high-stakes video poker. He mailed cookies to his elderly mother in Florida.

What we do know is that Paddock planned his mass murder meticulously. All of Paddock’s 47 guns–recovered by law-enforcement officials from his hotel suite, his home in Mesquite and another in Reno–appear to have been legally purchased across four states. After arriving at the Mandalay Bay on Sept. 28, he set about building his bunker. Over the course of three days, he ferried 23 guns, two tripods and hundreds of rounds of ammunition up to his room, one or two bags at a time. Below, in his car, he had bags of ammonium nitrate, which can be used to make a powerful explosive. As a high roller, he may have had his pick of the unclaimed rooms, free of charge. The elevators to his car bypassed the lobby.

No one bothered him until his massacre was in progress. He knew they were coming; he had rigged video cameras in the hallway to give him a warning when police approached. As law enforcement closed in, he put a handgun in his mouth and pulled a trigger for the last time.

The ease with which Paddock evaded security is a reminder of both how hard it is to stop a determined killer who hasn’t set off alarms in advance. Casinos have cameras everywhere, and officials are now reviewing hours of surveillance footage to see how he spent his weekend in a city best known for bachelorette parties, professional conferences and boys’ weekends away. And it wasn’t just the city’s wide-open attitude that may have made it an inviting target. The glitzy boulevard is a symbol of our culture of decadence: there’s a reason that the Islamic State released a 44-minute propaganda video in May calling for supporters to conduct attacks there.

But it is also now a place that exemplifies an American attribute, limited not just to Nevada: resigned resilience. At 8:30 a.m. on Oct. 3, less than 36 hours after the worst mass shooting in modern history began upstairs, guests at the Mandalay Bay were back on the casino floor. The slot machines were humming. Two poker tables were in full swing. Racing fans filled the sports book. It was hard to tell whether the reaction came from strength or acquiescence. But there it was: another roll of the dice, another pull of the lever.

–With reporting by SEAN GREGORY/NEW YORK; and TESSA BERENSON, NASH JENKINS, ZEKE J. MILLER and MAYA RHODAN/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlotte Alter / Las Vegas at charlotte.alter@time.com, Haley Sweetland Edwards / Las Vegas at haley.edwards@time.com and Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com