In the harrowing 38 minutes after an incoming-missile warning was mistakenly sent via Hawaii’s emergency alert system on Saturday, those who received the message scrambled to follow its instructions to seek shelter. The experience shocked a state and a nation whose citizens have often felt that the fear of a direct attack, especially a nuclear one, is a thing of the past. The days of fallout shelters and duck-and-cover drills have seemed over — though though perhaps less so these days, as the threat of conflict with North Korea looms, than at other times in the recent past.

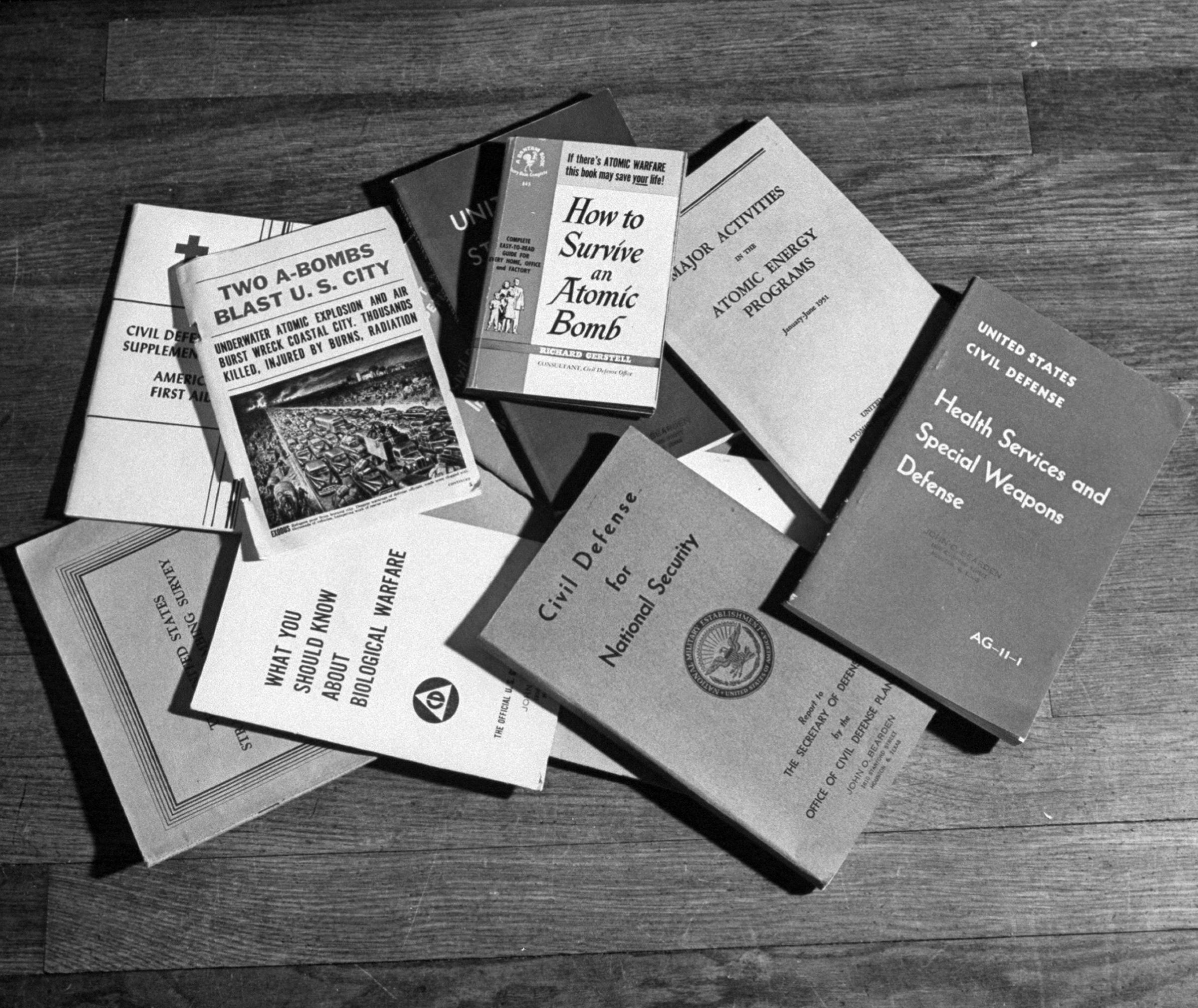

In 1954, LIFE Magazine captured that fear at its height, sending photographer John Dominis and Dallas correspondent Scot Leavitt to profile the Beardens of Houston. The photographs that resulted, a selection of which are presented in the gallery above, were never actually published by the magazine.

However, Leavitt’s notes from that March day, which he sent to the magazine’s editors, were preserved in the archives. They now offer insight into the psychology of a nation under the shadow of nuclear doom.

“Like a good many other Americans who live in large cities, John Bearden has the melancholy conviction that, sooner or later, his home and family will undergo an atomic attack,” Leavitt wrote.

Bearden, a tax accountant, had personal experience with disaster, though not on a nuclear scale: He happened to have been present, as a Red Cross worker, for the April 1947 disaster at Texas City, Tex., in which a ship loaded with ammonium nitrate fertilizer caught fire and triggered a series of explosions that resulted in hundreds of deaths throughout the industrial port city. He knew what it looked like when life in a seemingly ordinary American city was suddenly disrupted on an enormous scale.

Of course, a person could be killed in the initial blast. But if a person survived, he or she would then be left, potentially in a seriously injured state, to confront a city without public services, without police, without doctors.

“The people were what frightened me,” he told Leavitt of his experience in 1947. “They seemed to be nice people, like you or me. But they became animals. The thin veneer of civilization was blown off and they were dazed, crazed animals. I saw nice-looking men acting as ghouls, stealing rings from corpses. There was no controlling them.”

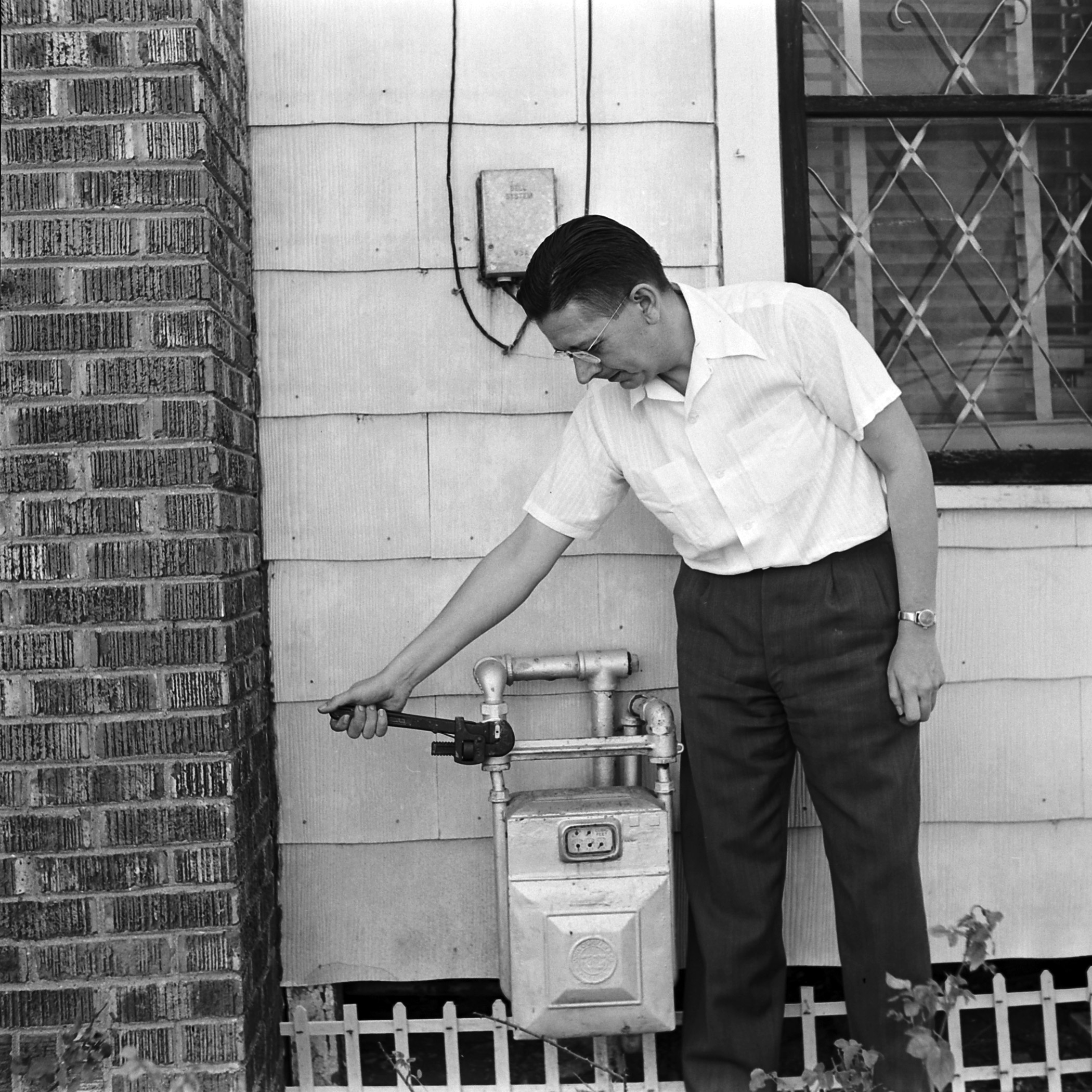

So Bearden decided that, while many of his neighbors scoffed at the measures he took, his family would be ready. Being able to act without having to think it through could save lives in an emergency. Preparation and practice were key. By the time the LIFE staffers met Bearden and his family — his wife Martha, four children and dog — they had prepared to face that inevitability for more than three years, ever since the adults had attended a nuclear safety seminar in 1950.

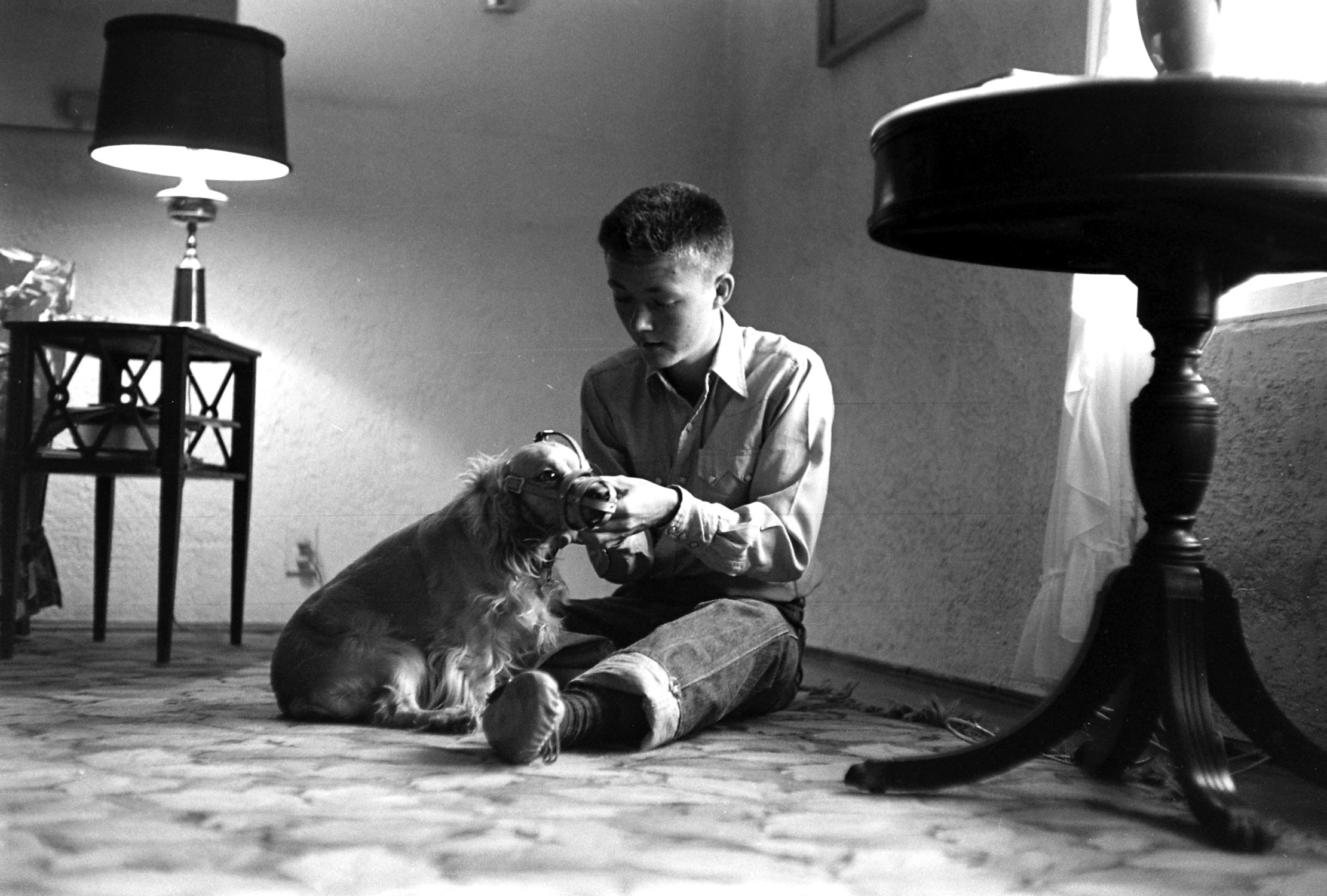

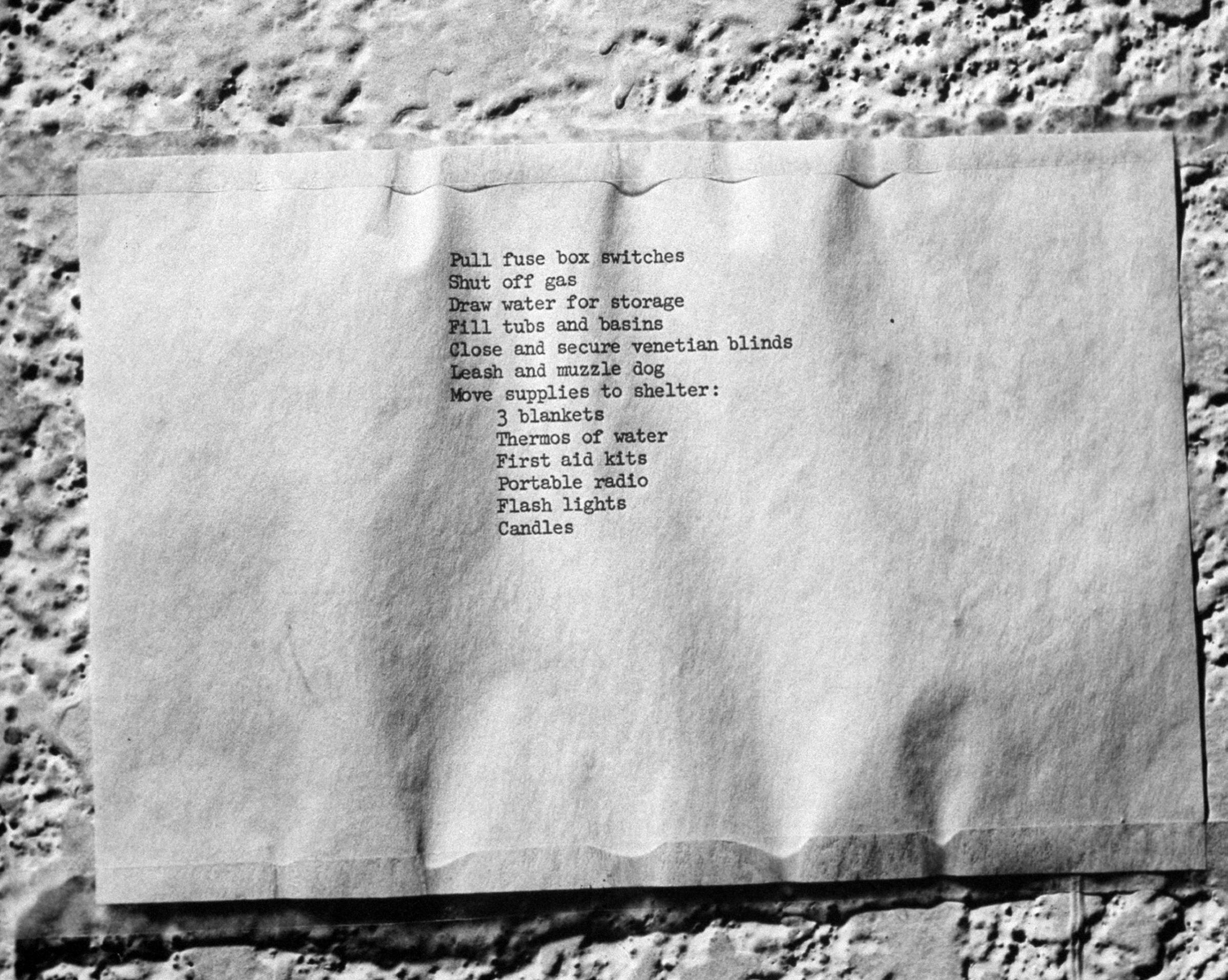

Although the family had not built themselves a shelter (a possibility they planned to explore later that year), they had put together a plan. Their 6-year-old twin daughters were taught to hit the ground at the sound of an explosion — a lesson they had put into action once, when a nearby fireworks factory exploded — and the older children had been given jobs such as drawing water in the bathtub and fastening the window blinds closed. If they had to leave home, they knew they could go to friends’ houses outside the city center and would meet there if they got separated. On the chance those homes were not an option, their teenage son, a scout, had been learning his way around the countryside. And along with what today might be called their “go bag,” they had a rifle, a pistol, a machete and an axe. And, John Bearden implied to Scot Leavitt, he would not hesitate to use those tools if a real need arose.

And how could the family prepare for the possibility that, in the event of a nuclear attack on Houston, there might not be time to put any of their plans into action?

“That part of the precautions,” Bearden told LIFE, “we take care of in church every Sunday.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com