For more than two years after Columbia University erupted in protest in the spring of 1968, U.S. college campuses were the scene of many violent demonstrations, building occupations, police busts and temporary campus closings. Now, recent events in Charlottesville, Va., suggest that the nation appears to be on the verge of a new era of protest, this time on our streets and in the parks of major cities. Though nearly 50 years have passed, the pattern that emerged in 1968-70 could be the template for what we are about to witness over the next few years.

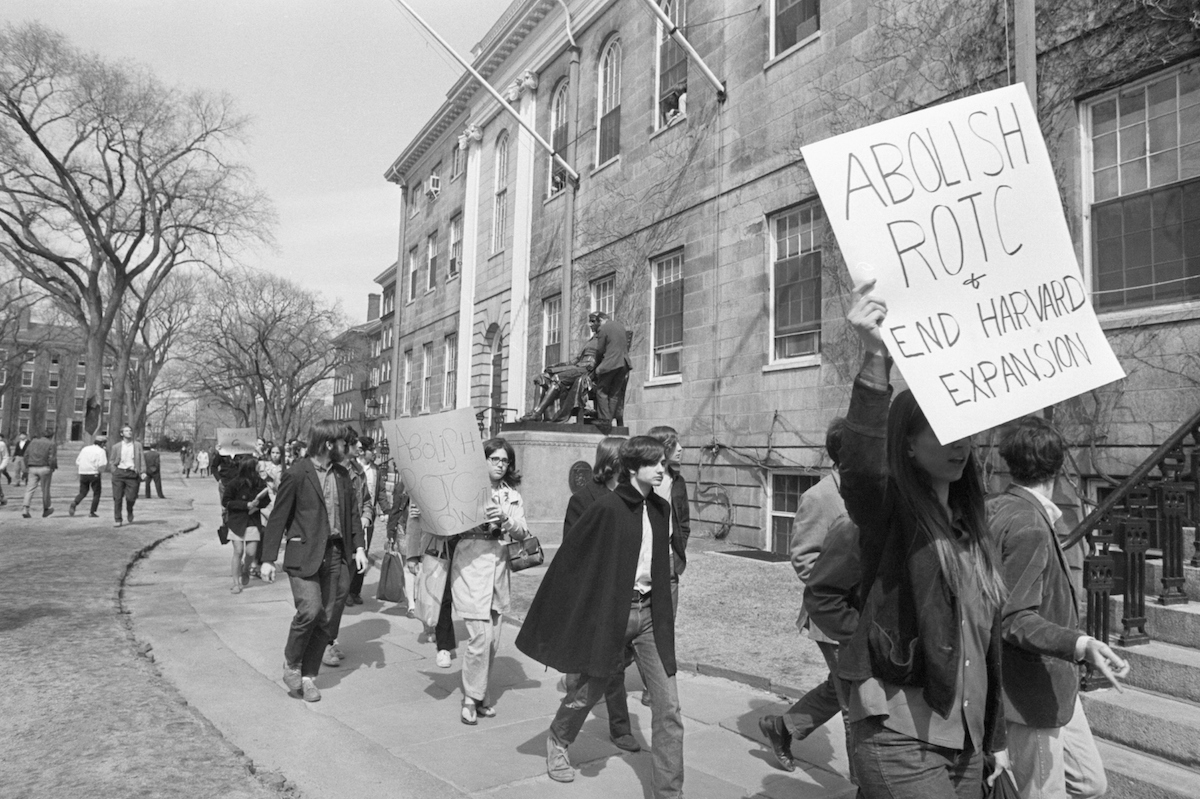

All around the nation in 1968-70, college students were becoming more and more hostile to the war in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. A huge earlier protest, at Berkeley in 1964-5, dealt with campus regulations, but by 1968 student hostility focused on the war. Gradually students shifted their hostility to symbols of the war on campus, such as research institutes doing work for the Department of Defense and ROTC programs. The most militant students—never more than a small minority—joined the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and sharply escalated these protests. ROTC buildings at various campus—including Kent State and Harvard—were set afire. And beginning at Columbia, students took the equally disruptive step of occupying administration buildings and rifling their files. In the spring of 1969, I saw this happen at Harvard.

The occupations never commanded the support of a majority of the student body. At Harvard, the occupation had not even been voted for by the majority of the SDS chapter. But the occupations triggered a response from school authorities, who summoned the police (and on some campuses, the National Guard) to remove the occupiers. They often did so violently. That, invariably, turned the bulk of the student body—who felt that the SDS was on the morally right side of the great issues of the day, even if they disagreed with their tactics—against the administration. Broader protests often led to the shutdown of universities for days or weeks.

The events in Charlottesville illustrate how something similar might happen today, as the response to the actions of relatively small militant groups draws in a wider section of the population.

The sparking incident in Charlottesville—the removal of Confederate monuments—is not new. It was months ago that Mayor Landrieu of New Orleans made the case for their removal by explaining that “there is a difference between remembrance of history and reverence of it,” and declaring frankly that the Confederates were on the wrong side of history and of humanity. (Personally, though an appeal to “history” is sometimes used to argue for keeping them, as a historian I believe that the removal is long overdue.) But these monuments are still an emotional issue for both right-wing extremist groups and a broader group of white southerners as well.

Extremist groups, including the KKK, gathered in Charlottesville to oppose the removal of Lee’s statue from the park. In response—critically—liberals of all kinds decided to demonstrate as well. An initially non-violent battle for the control of Charlottesville’s streets led to fighting between the two groups of demonstrators, and the Charlottesville government canceled the right-wing march. But the counterdemonstration continued and a car took the life of Heather Heyer. The man charged as the driver has been described by a former teacher as an admirer of Adolf Hitler. President Trump’s response to the incident created a huge controversy, and his statements in support of keeping Confederate monuments standing can only encourage more marches by right wing groups.

Marches and countermarches, some of them related to other Confederate monuments but many not, are now being planned all over the country. The possibilities for outbreaks of considerably worse violence are endless, and the marches cannot be stopped without declaring some sort of state of emergency, locally, or even nationally. Meanwhile, new controversies are sure to erupt over attempts to bring rioters to justice. Just as in the past, protests and counterprotests can escalate each other.

The experience of the late 1960s does not hold out much hope for how this cycle might end.

Two things stopped the university protests then: many universities essentially joined the protests, and the war faded from view. In the spring of 1970, after Nixon invaded Cambodia and four students were killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State, college administrations joined the side of the protesters, pre-emptively shutting down their institutions, canceling their exams and telling their students to use the time to protest against the war. But by the next year the U.S. combat role in Vietnam was almost over and draft calls were down. There were no serious campus protests when Nixon escalated the air war again in May 1972.

This time, however, the protests are not about a policy that might be modified or abandoned. Even if all of the statues are removed, we will still be divided by conflicting views of our identities as Americans—views that also divide our two major political parties. We might resolve this crisis by uniting in some great common enterprise to accomplish a critical task, as we did in the era of Franklin Roosevelt. On Wednesday, President Trump appealed to unity at a speech in Reno, Nev., but it is not easy to imagine what that task that might produce such a result might be — especially when, just the night before, he had rallied his supporters by attacking his opponents, and when he remains focused on a highly controversial wall.

We apparently lack the elements that brought the cycle of protest to an end in the 1970s. Barring unforeseen events, we may simply have to wait for our current conflict to burn itself out, leaving the quest for unity to a new generation.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- See Photos of Devastating Palisades Fire in California

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com