The power to create national monuments in the U.S. rests with the President, but the flip side of that responsibility has long been murky legal ground. Can the President unilaterally get rid of a national monument that already exists?

The Associated Press reported on Thursday that Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke had decided not to recommend that President Donald Trump eliminate any national monuments, though he would recommend that changes be made to the boundaries of some. And, though environmental advocates have promised to take the matter to the courts if Trump decides to actually shrink the monuments, that primary question about abolishing them now seems likely to remain without a solid answer for at least a while longer.

Zinke’s landmark review of 27 national monuments constitutes the first major test of the 111-year-old Antiquities Act of 1906, the legislation that established the American system of national monuments. To ward off looters who were raiding ancient sites in the American West, it gave the President the power to set aside “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest.”

Since then, 16 presidents have declared 157 national monuments. But the subtraction of such monuments is a much shorter history.

Delve into any research on the extent to which presidents can shrink or abolish monuments by proclamation and it will take you back to 1938, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was considering abolishing Castle-Pinckney National Monument.

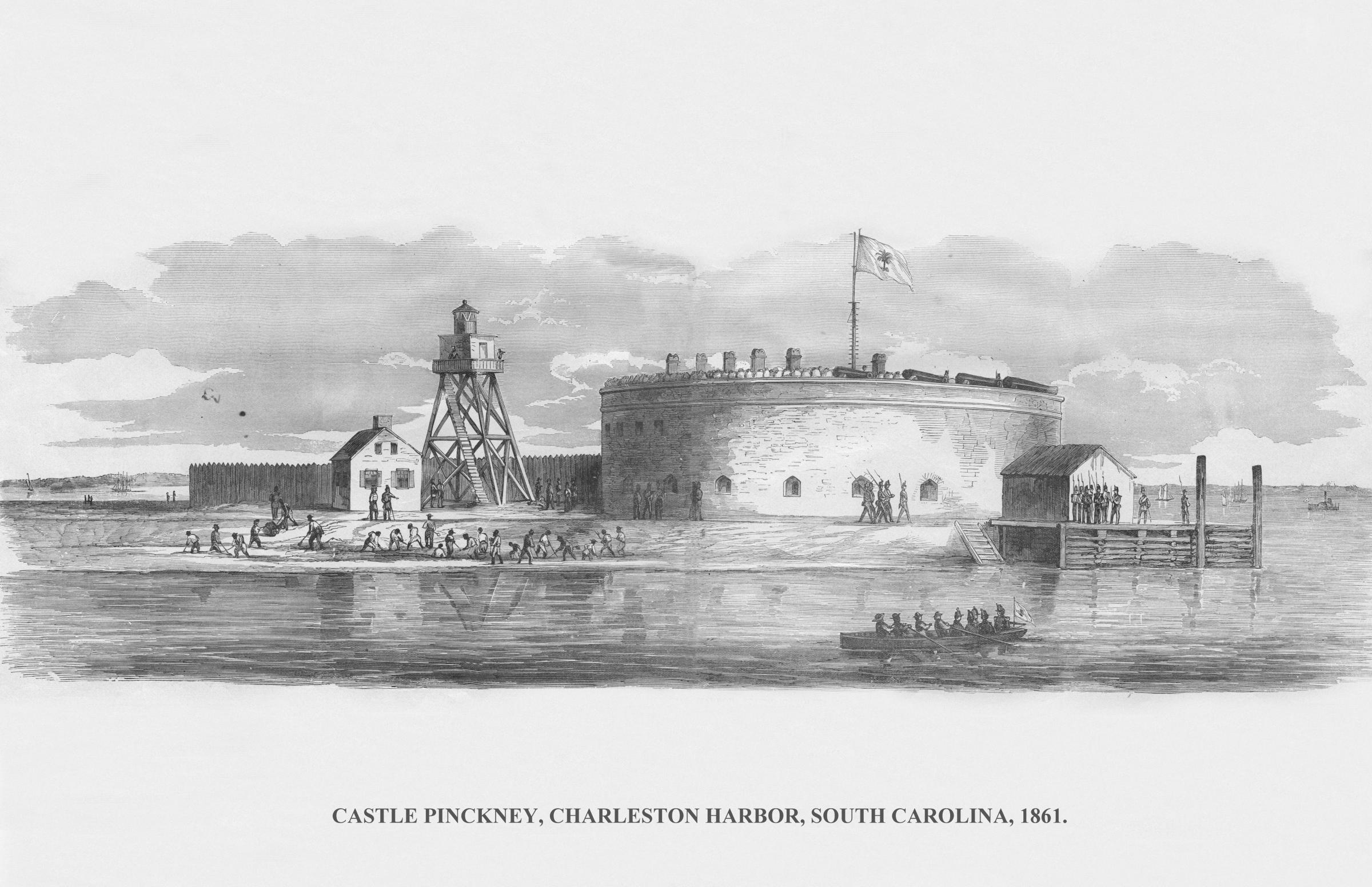

The claim to fame of this log fort on the island of Shutes Folly in Charleston Harbor, which had been designated a national monument in 1924, was that in 1860 it had become — without the use of gunfire — the first federal property seized in a Southern state, in this case, by the South Carolina militia a week after the state’s declaration that it was seceding from the Union.

But, by the 1930s, it had had its 15 minutes of fame. “It was in lousy shape, too expensive to restore, and didn’t have as glorious a past as Fort Sumter,” says Robert Janiskee, professor emeritus of Geography at the University of South Carolina and member of the Board of Directors of National Parks Traveler.

And yet, Roosevelt was advised that he could not simply cull the fort from the list of national monuments. His Attorney General, Homer Cummings, wrote in 1938 that the Antiquities Act did not give the President the right to revoke the designation. According to parts of his statement quoted by a 2016 Congressional Research Service report:

The statute does not in terms authorize the President to abolish national monuments, and no other statute containing such authority has been suggested. If the President has such authority, therefore, it exists by implication… While the President from time to time has diminished the area of national monuments established under the Antiquities Act by removing or excluding lands therefrom, under that part of the act which provides that the limits of the monuments “in all cases shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected,” it does not follow from his power so to confine that area that he has the power to abolish a monument entirely.

In the years since, though the number of national monuments has gone up and down, especially as some of those monuments have been made National Parks, FDR’s inquiry into whether he could get rid of a monument stood as precedent. None of the presidents who followed him completely abolished a national monument by presidential proclamation.

And yet, that was not the end of the story. Not all legal experts agree on what Cummings’ statement means. Experts such as Mark Squillace, the Director of the Natural Resources Law Center at the University of Colorado Law School and former Special Assistant to the Solicitor at the U.S. Department of the Interior in the Clinton administration, have said the Cummings opinion was legitimate and backed up by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, which specifies how public lands should be managed and preserved.

“In 1976, Congress passed a law that was quite clear that it intended to reserve for itself the power to revoke or modify, so whatever ambiguity might have existed in the Antiquities Act itself, I think Congress cleared it up in 1976,” he says. “Part of the argument for the Antiquities Act today is that the President needs that broad authority to act quickly to protect lands that might be threatened from different kinds of development, and if the Congress doesn’t like those decisions, it can reverse them. But in fact, Congress has never done so with any significant monument.”

But on the other hand, John Yoo, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law who worked in President George W. Bush’s administration, argues that Cummings’ recommendation was not binding and, in any case, Presidents undo what their predecessors do all of the time. “It is contrary to our constitutional designs for Presidents to be able to act unilaterally and permanently,” he says.

That’s why John Leshy, professor emeritus at the University of California Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco and former Solicitor of the U.S. Department of the Interior in the Clinton administration, concludes that “ultimately, the courts will have to tell us” how far the President’s power goes in that case — including the power to shrink national monuments, even though that’s something that chief executives have done in the past. President Woodrow Wilson famously cut Mount Olympus National Monument in Washington State in half amid concerns that the timber was needed for World War I. In 1941, FDR lopped off about 52 acres of Wupatki National Monument in Arizona so they could be repurposed for a dam. JFK redrew the boundaries of Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico by adding 2,882 acres, but chopping off 3,925 acres from land found to contain “limited archeological values.”

And as for Castle-Pinckney? Congress would end up abolishing that particular monument in the 1950s, anyway.

With reporting by Katy Steinmetz

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com