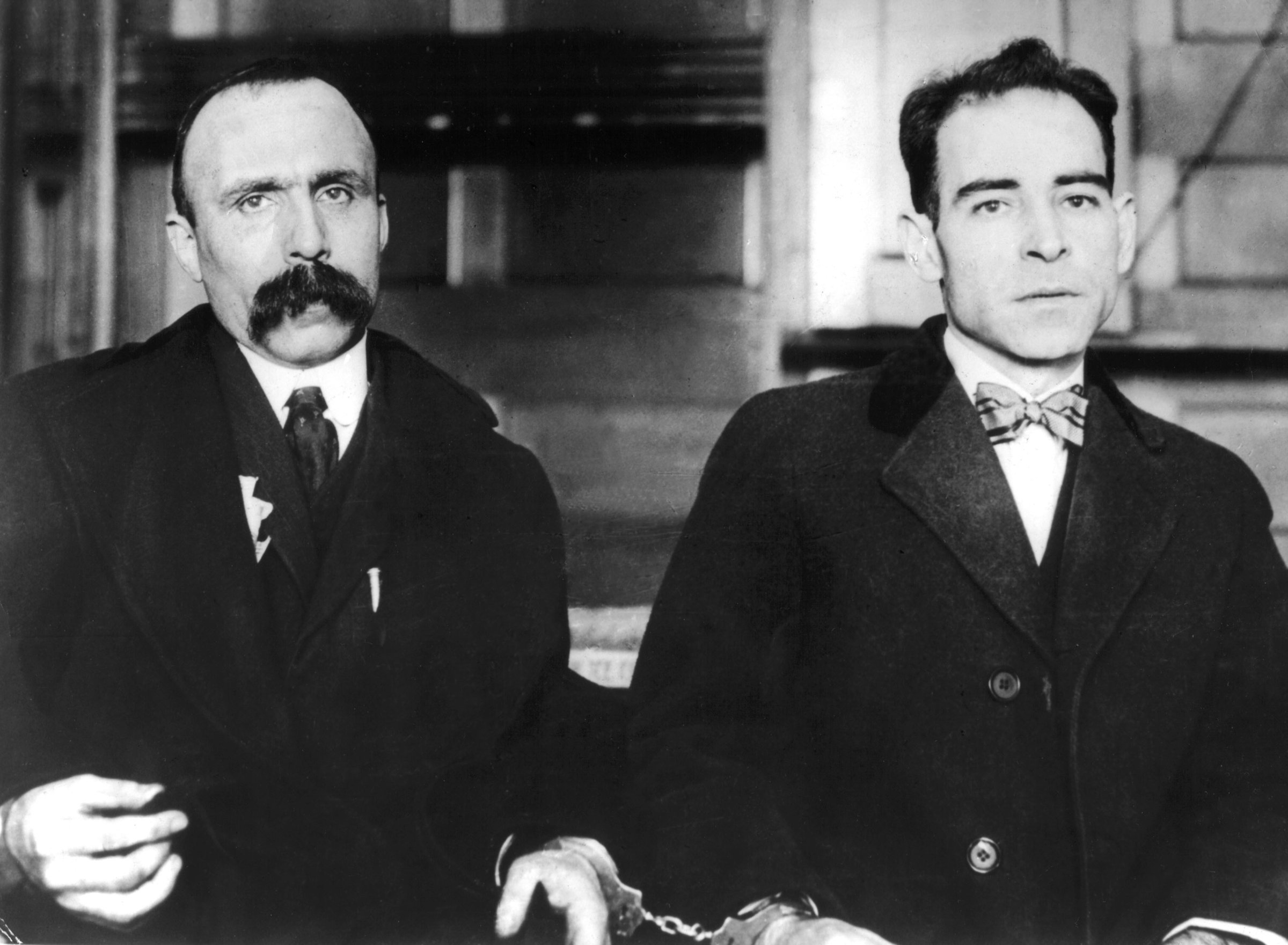

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti weren’t famous during most of their lives. They were, respectively, a shoemaker and a fish peddler. Their deaths, however, earned a front-page headline in the New York Times and TIME noted that fear of the reaction to the news led officials to close Boston Common to public speakers for the first time ever. And, 90 years after those Aug. 23, 1927, executions, the story of Sacco and Vanzetti is still taught in American classrooms.

On May 5, 1920, the two were arrested in connection with the murders of two other men, a shoe-factory paymaster and the man who had been escorting him while he transported about $15,700 in pay down the main street in South Braintree, Mass. A little more than a year later, a jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of robbery and murder — even though the evidence against the two was mostly circumstantial, according to Moshik Temkin, a professor of History and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and author of The Sacco-Vanzetti Affair: America on Trial.

There was plenty of reason to doubt that Sacco and Vanzetti had actually committed the crimes. The money was never recovered and neither suspect had a criminal record. Plus, another known criminal confessed to the crime. But, despite seven appeals, their request for new trial was rejected in October of 1926, and the two were sentenced to death in April of 1927. Temkin notes that it’s impossible to say for sure a century later, but that the idea that they were behind the murders just doesn’t line up.

What is for sure, however, is that they were Italian immigrants and anarchists, two groups that were subject to extreme suspicion at the time.

“Part of their misfortune is that they were the wrong people in the wrong place at the wrong time,” he says.

They were among the many immigrants living in poverty who, fed up by what they saw as the exploitation of workers in the capitalist system in the U.S., were drawn to meetings of anarchists who thought that the solution was to overthrow the government and start from scratch. In the 1920s, the U.S. government had been on the hunt for these people already; the judge to whom they appealed openly hated anarchists. Meanwhile, while Sacco and Vanzetti were in prison, quotas restricting Italian immigration quotas became law in 1924, partly because many Southern and Eastern Europeans weren’t considered white enough.

But, if the justice system had started out by making an example of Sacco and Vanzetti, it ended up making martyrs of them.

Protests took place worldwide—from Latin America to Morocco to China, and especially in western Europe, which had just ceded its dominance on the world stage to the U.S. after World War I. “There’s a resentment that comes with that,” Temkin says, “making Europeans a lot more sensitive to what happens inside the U.S.”

As Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Edna St. Vincent Millay framed the injustice, “[the] men were castaways upon our shore, and we, an ignorant savage tribe, have put them to death because their speech and their manners were different from our own, and because to the untutored mind that which is strange is in its infancy ludicrous, but in its prime evil, dangerous, and to be done away with.’’

During their six years on death row, their letters from prison further endeared the two to the general public and persuaded many people of their innocence. They came to be seen as philosophers, not criminals, as Temkin puts it. One example from Sacco, a father of two who enjoyed gardening in his spare time, shows his attempt to remain optimistic, and he notes that “between these turbulent clouds, a luminous path run always toward the truth.” Another letter by Vanzetti, however, shows how hopeless he felt:

O the blessing green of the wilderness and of the open land — O the blue vastness of the oceans — the fragrances of the flowers and the sweetness of the fruits…Yes, Yes, all this is real actuality but not to us, not to us chained.

The execution radicalized many young intellectuals, and a noteworthy number of those who lived in Massachusetts decided to move to New York in protest, which Temkin argues shifted the cultural balance of the two areas. On the legal front, the procedure of appeals changed so that defendants don’t have to keep going before the same judge. The two were subsequently immortalized in pop culture, from Woody Guthrie’s song “Vanzetti’s Letter” to an episode of The Sopranos.

In the end, in many ways, despite their deaths, what happened was just what Vanzetti himself had predicted. In May 1927, after the judge rejected the duo’s last appeal, he was quoted in the New York World in what would become his most famous words:

If it had not been for these thing[s], I might have live[d] out my life, talking at street corners to scorning men. I might have die[d], unmarked, unknown, a failure. Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, for justice, for man’s understanding of man as we now do by dying. Our words, our lives, our pains — nothing! The taking of our lives — lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler — all! That last moment belongs to us — that agony is our triumph.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com