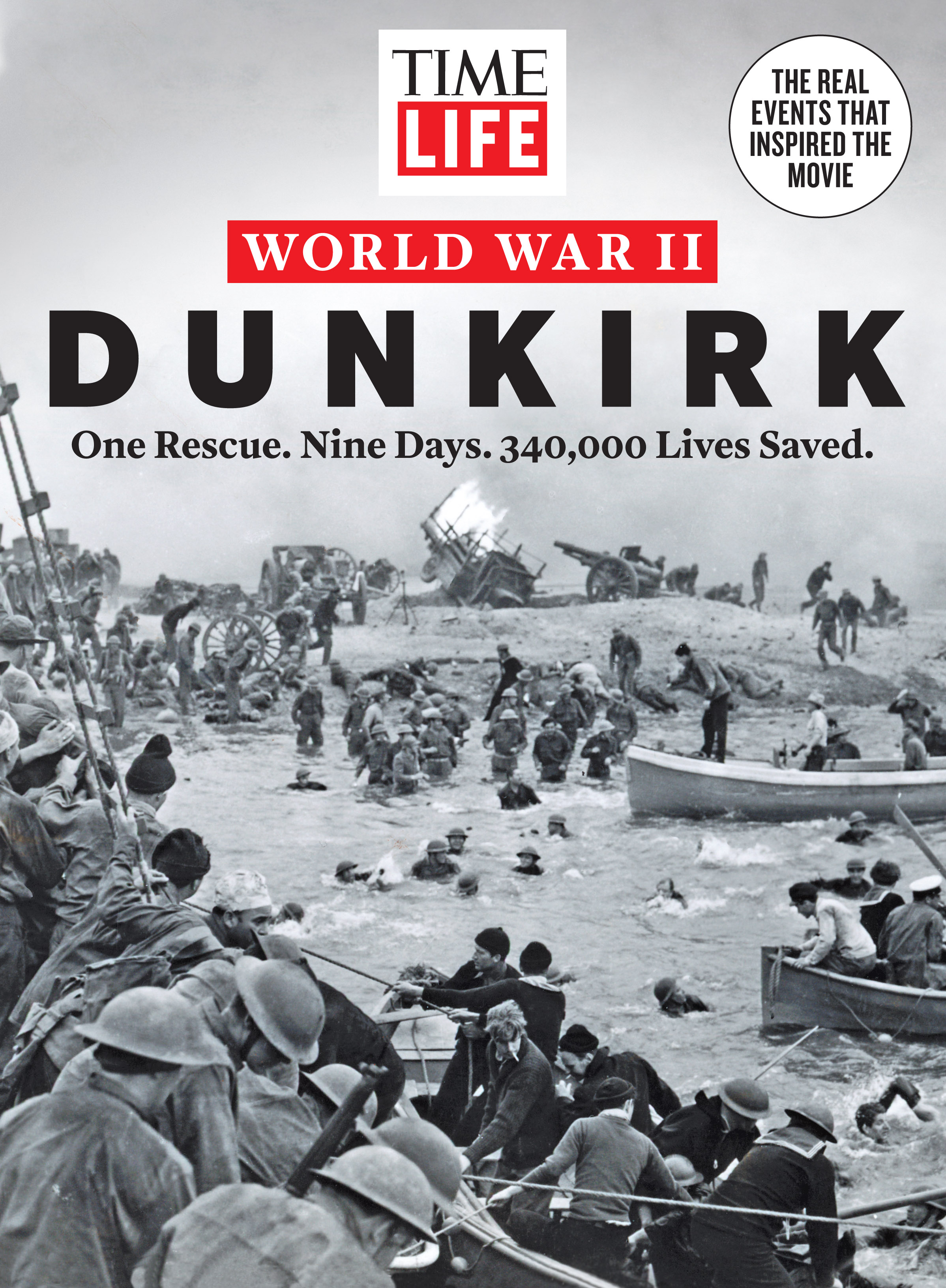

The 1940 evacuation at Dunkirk — the subject of Christopher Nolan’s critically acclaimed new film — remains one of World War II’s most striking episodes. However, for many troops, Dunkirk was only the beginning. The following is an excerpt from TIME-LIFE’s new special edition, World War II: Dunkirk, available on Amazon.

After the last rescue boats left Dunkirk harbor on June 4, 1940, the Germans captured some 40,000 French troops who’d been left behind as well as at least 40,000 British soldiers in the Dunkirk vicinity. Theirs is a story that is often overlooked, but for the next five years, until the war’s end, large numbers of these POWs would be mistreated and abused in violation of Geneva Convention guidelines governing the sick, wounded, prisoners of war and civilians. As described in Dunkirk: The Men They Left Behind, by Sean Longden, some were summarily executed. The POWs were denied food and medical treatment. The wounded were jeered at. To lower officer morale, the Nazis told British officers that they would lose their rank and be sent to the salt mines to work. They were forced to drink ditch water and eat putrid food. As noted by Longden: “These dreadful days were never forgotten by those who endured them. They had fought the battles to ensure the successful evacuation of over 300,000 fellow soldiers. Their sacrifice had brought the salvation of the British nation. Yet they had been forgotten while those who escaped and made their way back home were hailed as heroes.”

The crimes began as Dunkirk was being evacuated. On May 28, the SS Totenkopf Division marched about 100 members of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment, which had just surrendered, to a pit in a farm in Le Paradis and murdered them with machine gun spray. A similar atrocity unfolded on the same day with the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, which had been captured near Wormhout. They were forced into a barn and massacred with grenades.

As the war dragged on, forced marches became more common, sometimes with very little food or none at all — one British battalion reported receiving only two sugar lumps and two tablespoons of a mixture of carrots and potatoes a day. On arriving at train stations the POWs were loaded into cattle cars for trips to work sites in Germany and Poland.

British soldier Charlie Waite’s story was not uncommon. A 20-year-old from Essex, Waite was captured on May 20. He was moved from place to place and kept prisoner on a farm in Poland and forced to work the fields with Nazi guards watching. In the frigid winter of 1944–45, on a forced march of nearly a thousand miles from Poland to just outside of Berlin, Waite almost died. He finally was rescued in April by Allied forces as the war was drawing to a close. He described his two forced marches, one when he was captured in 1940 and the second in 1945, in his book, Survivor of the Long March: Five Years as a POW: “[The first march] was in hot weather and I was still wearing my greatcoat but I was in good physical shape. But in 1945, we had the additional challenges of one of the coldest winters on record that January, of having suffered years of misery, fear, exhaustion and starvation and of watching fellow men die and helping to bury them by the roadside. Those are things you never forget.”

British soldier Peter Wagstaff recalled similar treatment. Just 20 when he was captured, Wagstaff and his fellow POWs were threatened by their Nazi captors. Some were killed. “The Kommandant, a German we called the ‘Purple Emperor,’ told us, ‘If you look out of the window you are going to be shot.’ One officer said he was still going to do it — and he was shot. But you took it because it was part of life. You accepted it. This was happening all the time. You didn’t have time to analyze yourself. You are fighting to keep alive.”

France Surrenders

Meanwhile, the French military was in tatters and seemed poised for defeat. From the day of the German invasion on May 10 through the evacuation of Dunkirk, France had lost 24 infantry divisions, including six of seven motorized divisions. Instead of four armored divisions equipped with 200 tanks each, the country now had three, each equipped with 40. The new French commander, Maxime Weygand, transferred soldiers from the Maginot Line, but could muster only 43 infantry divisions to face the Third Reich’s 104. Allied assistance had disappeared. The British had withdrawn all but two divisions south of Dunkirk, and the Belgian Army had surrendered.

The French were further hampered by a lack of strategic clarity. Premier Paul Reynaud favored a Dunkirk-like evacuation to North Africa, where the army could be protected by the French Fleet and the Royal Navy while it reconstituted itself, gathered additional forces from the French colonial empire and took delivery on a fleet of planes from the U.S. Commander Weygand, however, opposed such a move and vowed to remain on French soil to defend his homeland. Within Reynaud’s cabinet, there was an appeasement faction, coalescing around Deputy Premier Marshal Pétain, which was considering a potential deal with Adolf Hitler.

General Alan Brooke returned to France to command the few remaining British units and judged the situation untenable. In a tense conversation with Churchill, Brooke demanded a further evacuation, and when Churchill argued that a British presence was needed to make the French feel supported, Brooke replied: “It is impossible to make a corpse feel.”

The French fought as well as they could, relying on small groups of troops and armaments gathered into tight factions called “Hedgehogs.” From June 5 to June 7, these pockets of resistance slowed the Germans as they crossed the marshes of the Somme River at Hangst in the west and at Péronne in the east. At Amiens, 90 miles northwest of Paris, the German 10th Panzer Division lost two thirds of its tanks in just three days. The 7th Panzer Division, led by Erwin Rommel, finally broke through in the west and charged 20 miles south of the Somme to cut off one British division, which retreated and later evacuated. As the days proceeded, Rommel simply directed his Panzers around the remaining Hedgehogs, and the French were unable to mount an effective counterattack.

It didn’t take long for the Germans, whose Panzers were rolling rapidly through the country, to wear down the French. Paris fell on June 14.

On June 17, Rommel covered 150 miles westward and on June 19 he captured Cherbourg. The French government, which had been in a state of crisis for weeks, signed an armistice on June 22. The agreement divided France into two parts, the northern half under direct German occupation and the south under a puppet regime led by Pétain. It had taken the Germans just 18 days after Dunkirk to capture France.

British Fortitude

Britain now stood alone against the Nazis and many wondered whether it would be the next to concede. Some members of the British government, beginning to regret the rise of the uncompromising Churchill, considered what sort of an agreement might be reached with the German leader. Hitler tentatively planned for a British invasion, code-named Operation Sea Lion, but he knew that such an incursion would be risky, difficult and very costly, and so he waited for a British peace offer.

Churchill was having none of it. Brilliantly spinning the defeat at Dunkirk into an expression of the “Dunkirk spirit,” Churchill urged his people to display the grit of the British troops and the can-do attitude of civilians who volunteered their ships for the rescue operation. He quickly replaced the equipment lost in France. He began currying a relationship with U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, who signaled his intention to assist the British in any way he could. And in July, when Hitler’s bombers began attacking English cities in an effort to force surrender, Churchill prepared the nation for the three-month-long siege that would come to be called the Battle of Britain.

On August 20, as the aerial conflict entered its most intense stage, Churchill took to the airways to pay tribute to the courageous pilots of the RAF: “The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the world war by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

On September 15, the Luftwaffe launched over 1,000 aircraft in the campaign’s most concentrated bombing raid yet against London. The assault failed to produce the desired results, with the British capital escaping serious harm. Instead, 20 German planes were damaged and another 60 shot down. To cut his losses, Hitler scaled back the raids in favor of the limited nighttime strikes known as the Blitz, which continued until May 1941.

The RAF had stood up to the Luftwaffe and won. The threat of a German invasion was over. Soon, as Churchill predicted, the “tide of the world war” would shift toward the forces of freedom. During the next five years, Churchill and the British leadership were able to expand the size of the British army, add new planes to the resources of the RAF, repair and replace the ships lost at Dunkirk and reestablish the British Navy as one of the most powerful in the world. Newly fortified, British soldiers fought against advances in North Africa and the Middle East by the Axis forces.

Without Dunkirk, none of this would have been possible, nor would Britain have been able to hold out until December 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought the Americans into the war as a critical ally.

When the Allied forces landed in Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944, three of the eight divisions that took part were British. Two were dropped from the air and one arrived by ship and stormed the beaches beside its American allies. The victory that followed was sweet for all involved, but for the British, it was more than that. It was redemption.

Read more in TIME-LIFE’s new special edition, World War II: Dunkirk, available on Amazon.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Introducing TIME's 2024 Latino Leaders

- How to Make an Argument That’s Actually Persuasive

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- The Ordained Rabbi Who Bought a Porn Company

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com