The story of the World War II evacuation at Dunkirk — the subject of Christopher Nolan’s well-reviewed new film — starts well before the men who were part of one of the most famous events in modern British history reached the beach.

It starts in May 10, 1940, with a surprise German blitzkrieg bombarding Holland and the French-Belgian border with air raids, parachute drops and ground attacks. The move came as a surprise to the Allied forces, who had thought any German attack would come at the Maginot Line, a fortification along the French-German border. And it was apparently a surprise to some Germans too, according to Robert Tombs, a historian at the University of Cambridge and a co-editor of Britain and France in Two World Wars: Truth, Myth and Memory, since it was a risky last-minute decision that Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler almost didn’t sign off on.

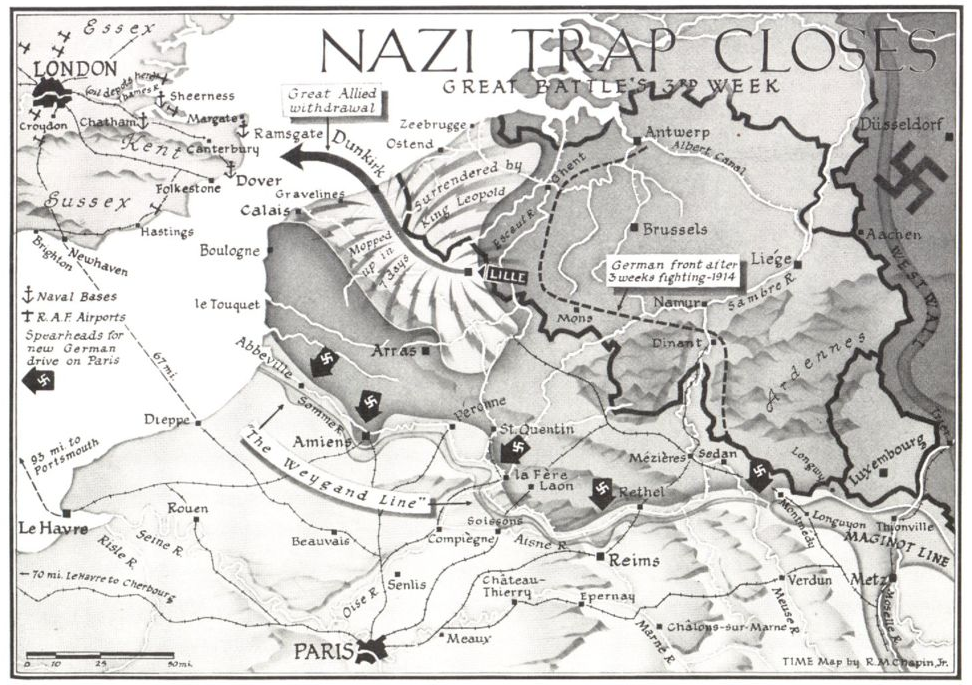

Belgium and Holland were hit so hard they were forced to surrender, and British troops in France, pushed toward the water by the onslaught of German forces, fought themselves to a point of no return at the French port of Dunkirk. (This map, from the June 10, 1940, issue of TIME, shows the small and shrinking sliver of land onto which they were driven.)

“Their only chance of surviving was for the army to be brought back to England, [to] protect the island and carry on the war,” says Tombs. “If this had not succeeded, Britain might have had to surrender to Hitler and Germany would have dominated Europe.”

But, if they hoped to escape back to England, they had a logistical problem: the beach at Dunkirk was so shallow that the big ships of the Royal Navy couldn’t reach the stranded soldiers. In a stroke of ingenuity, a call went out for civilian boats to head to Dunkirk to ferry the troops to safety. Complicating the already harrowing rescue was an air raid midway through the operation by the German Luftwaffe. To keep cargo light on the small ships, the troops had to leave their weaponry, tanks, and artillery behind, so that the small boats wouldn’t be overloaded. (“There’s a myth that the British army was unprepared,” Tombs says, but in fact it was just outnumbered, and records show that the Germans marveled at the high-tech quality of the abandoned gear at Dunkirk.)

The evacuation is often referred to as “the miracle of Dunkirk” because only 30,000 to 45,000 were expected to be rescued, but in fact, between May 26, 1940, and June 3, 1940, more than 300,000 troops were able to get off the beach.

That impressive result was thanks partly to the 800 to 1,200 boats (many of which were leisure and fishing crafts) that brought the men back and forth to the warships anchored in a deeper part of the English Channel. “Operation Dynamo” — so called after the type of generator “once used in the room where the staff directing the operation were now based,” according to the Imperial War Museum — was a success. The rescued were given a heroes’ welcome before being sent back to other theaters of war.

In the wake of the retreat, Winston Churchill delivered one of his most famous speeches at Parliament on June 4, 1940. The rousing address is considered to be a turning point in morale, when Brits realized that if they could pull off the impossible, then they could win the war:

[We] shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender…

Churchill and the British government, however, often downplayed the critical role that French troops played in the rescue effort — and critics say the 2017 film doesn’t give them enough credit either. “I think the thing the British entirely forget or have never known, is that it was actually the French army that was helping to hold the Germans off and sacrificing themselves while the British army was evacuated,” says Tombs. “A lot of Brits think that the French didn’t fight, but the French army helped to save the British army.”

Nevertheless, nearly 80 years later, the “Dunkirk Spirit” remains a touchstone in British culture, and a reminder to face obstacles with the same tenacity and cooperation that got the Second World War troops through that dramatic evacuation and the years of war that were yet to come.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com