As part of TIME’s look at the changing face of America’s summer work, we asked entertainers, CEOs, writers and other influencers to tell us about their most memorable summer jobs. Here are the stories of the gigs that shaped them:

LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA

I was a cashier at the since-closed McDonald’s on 91st Street and Columbus Avenue in New York City. I worked the 10-to-2 shift, so I had to deal with the people who missed breakfast and still want breakfast even though it’s 11:15—no longer an issue now that they serve it all day. During rush hour one day, someone handed me a bill, and I looked at it pretty carefully: it was a $20, but George Washington’s face was on it. I was like, “Oh, sh-t, someone’s taped 20s to the corner of this $1 bill!” Given how much time I’ve spent with George Washington later in life, to catch him on the wrong bill was pretty wild.

Miranda is the creator of the musicals Hamilton and In the Heights

URSULA BURNS

In two summers helping clean up Central Park during high school, I learned how to organize to get the job done and what a team dynamic really meant—lessons that helped shape the way I worked in business.

Burns is the former CEO of Xerox

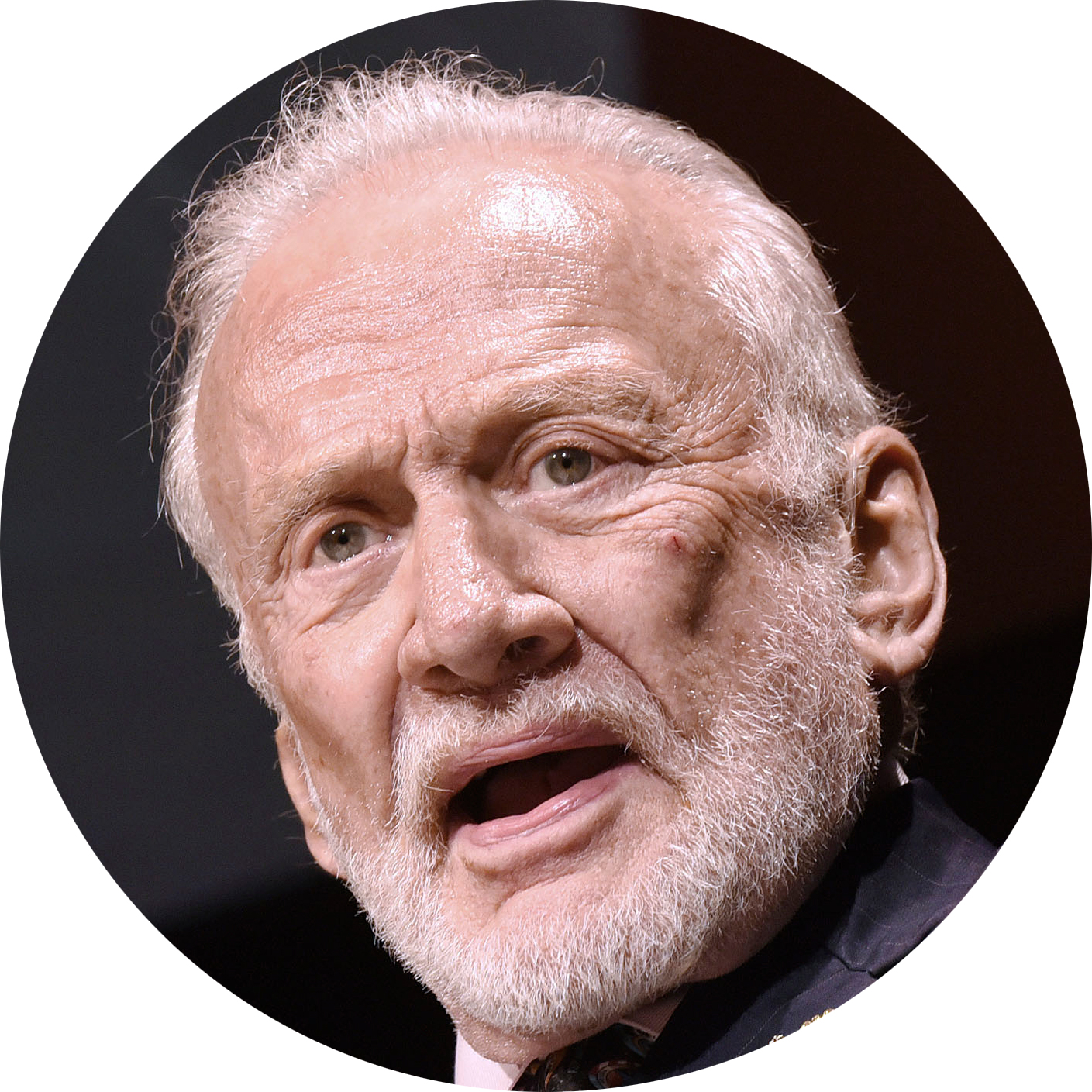

BUZZ ALDRIN

Growing up in Montclair, N.J., I took a job as a camp counselor. Working in the camp kitchen, two of us visited a nearby farm to get veggies. Farmer Allan tutored us in the fine art of carrot pulling, then left us. We gathered carrots, up and down the rows, all sizes and types. The farmer returned, aghast. “You damn city boys. Don’t pull up everything! You reach around and see if the carrot is big or not. The small ones, leave them be.” That was a farming lesson I’ll never forget.

Aldrin, the second man to walk on the moon, is chairman of the ShareSpace Foundation

JAMES PATTERSON

During a summer I spent working as an aide at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., James Taylor was a patient, and he used to hold informal miniconcerts in the hospital cafeteria a couple times a week. That same summer, Ray Charles came in for a few days and he had nothing better to do but play the piano and sing. Finally, Robert Lowell was a patient, and he used to hold poetry readings in his room for the three psychiatric aides (including myself) who hoped to be writers someday. Hell of a summer job!

Patterson is the best-selling author of more than 150 books

CHERYL STRAYED

The best and hardest of my teenage jobs (and I had plenty) was the summer I worked for the Youth Conservation Corps at the Rice Lake National Wildlife Refuge near my hometown of McGregor, Minn. I don’t recall my job title, but laborer sums it up. It was hard. On day one, I was issued a pair of steel-toed boots, work gloves and a helmet I’d seldom remove. In the sun and the rain and always swarmed by black flies and mosquitos, I and my teenage co-workers did whatever the adults instructed us to do. With handsaws we cut a path through the forest wide enough for a fire truck, and with nets we caught bullheads and flung them onto the pond’s shore. We waded into a bog to find and remove decades-old barbed wire and scraped old paint from the refuge’s outbuildings. We scrubbed public pit toilets and scythed chest-high weeds from ditches. We did what my mother called honest work. And she was right. It was honest. By day’s end I was so dirty and tired and blinded by my own sweat, I couldn’t anymore pretend who I’d been pretending to be. Someone weaker. That job obliterated her.

Strayed, a writer and advice columnist, is the author of Wild

ANDRA DAY

I used to work for a company in San Diego, Party Animals, where I would go to kids’ parties in costume as characters like Elmo and Dora the Explorer. I have a really deep voice, but I practiced my squeak and laugh so I could play a convincing Minnie Mouse for one gig. But when I got to the birthday party, the kids freaked out—apparently a giant rat is not what a 1-year-old girl wants to see! That was the moment when I realized I did have the drive to make music work and I was willing to do whatever job it took to get there.

Day is a singer-songwriter

ROBIN HAYES

I got into the airline business more by accident than anything. After college, I took a summer job selling duty-free in the Boston airport. The British Airways people were the nicest to me, so I applied for a job and was lucky enough to be hired.

Hayes is the president and CEO of JetBlue

SHERMAN ALEXIE

In 1990, I needed a summer job in Spokane, Wash., and didn’t want to fry hamburgers or deliver pizzas or sell doughnuts yet again. So I applied for a clerk position in an electronics company. It was a permanent position, but I said that I was taking an indefinite break from school “to figure things out.” I got the position because I typed faster than everybody else who applied.

A few days into the job, I saw my boss pour her leftover coffee onto a potted plant in her office. “Wow,” I remember thinking. “I didn’t know plants like coffee.” Of course, my boss was actually pouring water onto her plant so I didn’t realize until too late that I was slowly killing the office plants by feeding them leftover coffee. I didn’t understand the deadliness of coffee until I’d killed three cacti. At a team meeting, my puzzled boss asked the assembled workers if they knew anything about a plant-killing virus that smelled sweet and milky. I didn’t confess to my botanical crimes.

I quit that job three months later. I quit over the phone. But I didn’t speak directly to my boss. I called the receptionist in another department and told her that I was going back to college. That was my summer of lies and evasions and carelessness and murder-by-caffeine. All for minimum wage.

Alexie’s most recent book is You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me: A Memoir

MAYA LIN

One of my first summer jobs was as an intern for Pamela Callahan at an architecture firm in my small hometown of Athens, Ohio. She was smart and funny and it wasn’t until much later in my career, having never again worked for a woman at a firm, that I realized how important it is to have female role models and how few and far between they were.

Lin is an architect, designer and environmentalist

STEWART BUTTERFIELD

When I was 14, I had a summer job at the concession stand of a small movie theater. People lined up outside waiting for the previous show to end, and once they entered we had a crush of hurried customers. The inefficiency was too much for me to take. I started going out with a tray and napkin, French waiter–style, to take people’s orders in advance. Happier customers, less of a rush for us and, as a bonus, I even earned some small tips.

Butterfield is the co-founder and CEO of Slack

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com