When many Americans think of the birth of the civil-rights movement, they may think of event in the mid-1960s or just before that decade. But in fact, one of the earliest headline-grabbing demonstrations for civil rights took place a century ago this Friday.

The story had begun weeks earlier, when two plainclothes detectives in an unmarked Model T in East St. Louis, Ill., were shot by black citizens. In the aftermath, on July 2, 1917, a mob of white residents went after African Americans in the city, resulting in the deaths of at least 48 residents — 38 of them black men, women and children — and injury to hundreds more, as people were clubbed and pulled off streetcars. Buildings were set on fire, racking up $373,000 in damages (which would be almost $7 million in 2016) by some counts.

As it turned out, the people who shot at the undercover cops had mistaken their car for one of the many Model Ts driven by whites who had been going through black neighborhoods throughout that springtime, shooting at the windows of their homes and stores. Around that time, fake news stories were running in local newspapers, containing inaccurate reports of African Americans committing crimes including rape says Harper Barnes, a former critic for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and author of Never Been A Time: The 1917 Race Riot That Sparked The Civil Rights Movement. As a result of those events, African Americans had been armed out of self defense.

What happened in East St. Louis “was the first major race riot of the World War I period,” says Barnes.

This fake crime wave was being attributed to the real nationwide migration of blacks moving up from the South to northern industrial cities in the 1910s, lured by higher-paying jobs. As populations moved into much closer geographic spaces, fear and resentment grew, especially during the tense time after America’s entry into World War I in April 1917. Amid labor tensions, many white workers saw black social mobility as a threat. “The meatpacking bosses recruited black labor to replace striking white workers,” says Clarence Lang, professor and chair of the department of African and African-American Studies at the University of Kansas.

New government contracts prompted labor disputes, and strikers were accused of being unpatriotic for holding up production. And it wasn’t just a matter of meatpacking. The government worried this would happen at the Aluminum Ore Company in East St. Louis, the only factory in north America that processed boxes of ore into aluminum. As Malcolm McLaughlin, historian and author of Power, Community and Racial Killing in East St. Louis, explained to TIME in an email, black migrant workers were “employed not only to take on the strikers’ jobs but also frankly to rub their noses in it: you are siding with the enemy; you have no power; we will replace you with people you despise.”

Historians believe that white residents’ resentment of African-American strikebreakers is what led to the drive-through shootings in predominantly African-American neighborhoods.

After the July 2 riot, W.E.B. DuBois and Martha Gruening went to the city to talk to witnesses and survivors of the tragedy, and wrote an essay on the event for the NAACP’s The Crisis. It contained gruesome details of the riot and made the argument that violence against the black community of East St. Louis was bad for the economy:

So hell flamed in East St. Louis! The white men drove even black union men out of their unions and when the black men, beaten by night and assaulted, flew to arms and shot back at the marauders, five thousand rioters arose and surged like a crested stormwave, from noonday until midnight; they killed and beat and murdered; they dashed out the brains of children and stripped off the clothes of women; they drove victims into the flames and hanged the helpless to the lighting poles. Fathers were killed before the faces of mothers; children were burned; heads were cut off with axes; pregnant women crawled and spawned in dark, wet fields; thieves went through houses and firebrands followed; bodies were thrown from bridges; and rocks and bricks flew through the air…

It was the old world horror come to life again: all that Jews suffered in Spain and Poland; all that peasants suffered in France, and Indians in Calcutta; all that aroused human deviltry had accomplished in ages past they did in East St. Louis…

Eastward from St. Louis lie great centers, like Chicago, Indianapolis, Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York; in every one of these and in lesser centers there is not only the industrial unrest of war and revolutionized work, but there is the call for workers, the coming of black folk, and the deliberate effort to divert the thoughts of men, and particularly of workingmen, into channels of race hatred against blacks. In every one of these centers what happened in East St. Louis has been attempted, with more or less success.

On a local level, all that residents saw in the aftermath was increased segregation. The neighborhoods in which the city’s black population lived had been eyed by businessmen for commercial real estate development purposes, and the rioting provided an excuse to get some of that going, says Charles Lumpkins, a historian at Penn State University an author of American Pogrom: The East St. Louis Race Riot and Black Politics.

Outside of East St. Louis, however, there was outrage that lynching wasn’t just something that happened in the South. It was happening in the booming, northern industrial cities, so a Congressional inquiry followed, “justified on the basis that the riots had disrupted interstate commerce,” says McLaughlin.

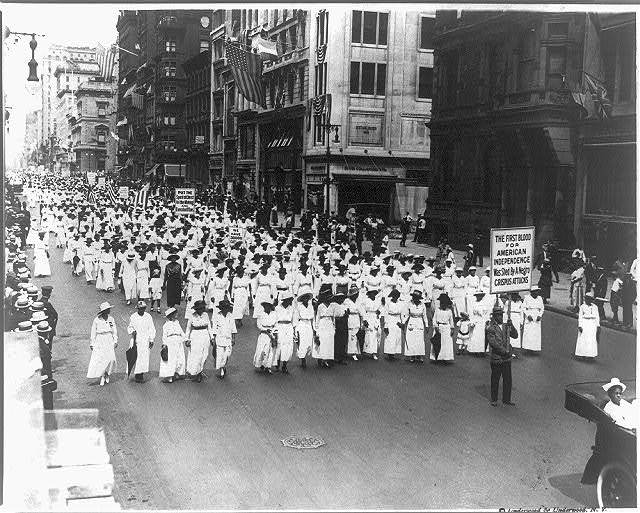

The rioting helped focus anti-lynching legislation efforts — and led to the “Silent Protest” parade on July 28 of that year, in which as many as 10,000 African Americans marched in silence down New York City’s Fifth Avenue. It was intended to raise awareness of and send a message to President Woodrow Wilson (who promoted segregation in the civil service) about the “lawless treatment” of African Americans, as the New York Times reported in 1917. It’s that march that’s now seen by many as the first march of the 20th century civil-rights movement.

As McLaughlin puts it, the rioting in East St. Louis in 1917 and the subsequent protests represent “the beginnings of a modern, national approach to civil rights.”

Correction, Aug. 18

A photo caption in the original version of this story misstated the year during which the parade took place. It took place in 1917, not 2017.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com