In the roughly two and a half centuries since America first celebrated its independence, there have been plenty of opportunities for moments big and small to sway the course of the nation’s history.

That’s why, to mark the Fourth of July holiday, TIME History asked 25 experts to pick one such moment. It could have happened on a day that every American child learns about in school — the day Abraham Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg, for example — or it could have happened on a day that might otherwise blend into the rush of history. Big or small, however, it had to have made its mark.

In past years, we’ve looked at such moments in the 20th century — you can see those lists here and here — but this year we’re going back in time even more, to the 19th century. The only rules were that the selections had to be specific moments (so that means “the Civil War” doesn’t work) and they had to have happened between Jan. 1, 1800, and Dec. 31, 1899. The results, contributed by email and phone, highlight 25 days out of the hundreds that passed during that century and, in doing so, trace the nation’s evolution from infancy to modernity.

The U.S. Naval Fleet Enters the First Barbary War (May 13, 1801)

After 9/11, many pundits claimed that the first war fought by the United States was against Islam. They were referring to the Barbary Wars of the early 19th century, which were fought by the early republic against the city-states of North Africa that had supported acts of piracy against American shipping and the enslavement of American sailors. To say that it was a war against Islam, however, completely misinterprets the events. Just a few years prior, Congress passed the Treaty of Tripoli (1797) whose Article 11 expressly stated that “the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.” At a time of intense political polarization, this simple statement was unanimously ratified by the U.S. Congress and signed by President John Adams. The reason why the Barbary Wars matter is much simpler, and much more important — and it’s why some historians consider the Barbary Wars the “second American Revolution.” This oft forgotten moment in American history was the first foreign conflict that brought together once disparate colonies into a united republic.

Mark G. Hanna is the Associate Director of the UC San Diego Institute of Arts and Humanities and author of the Frederick Jackson Turner Award-winning Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire: 1570-1740.

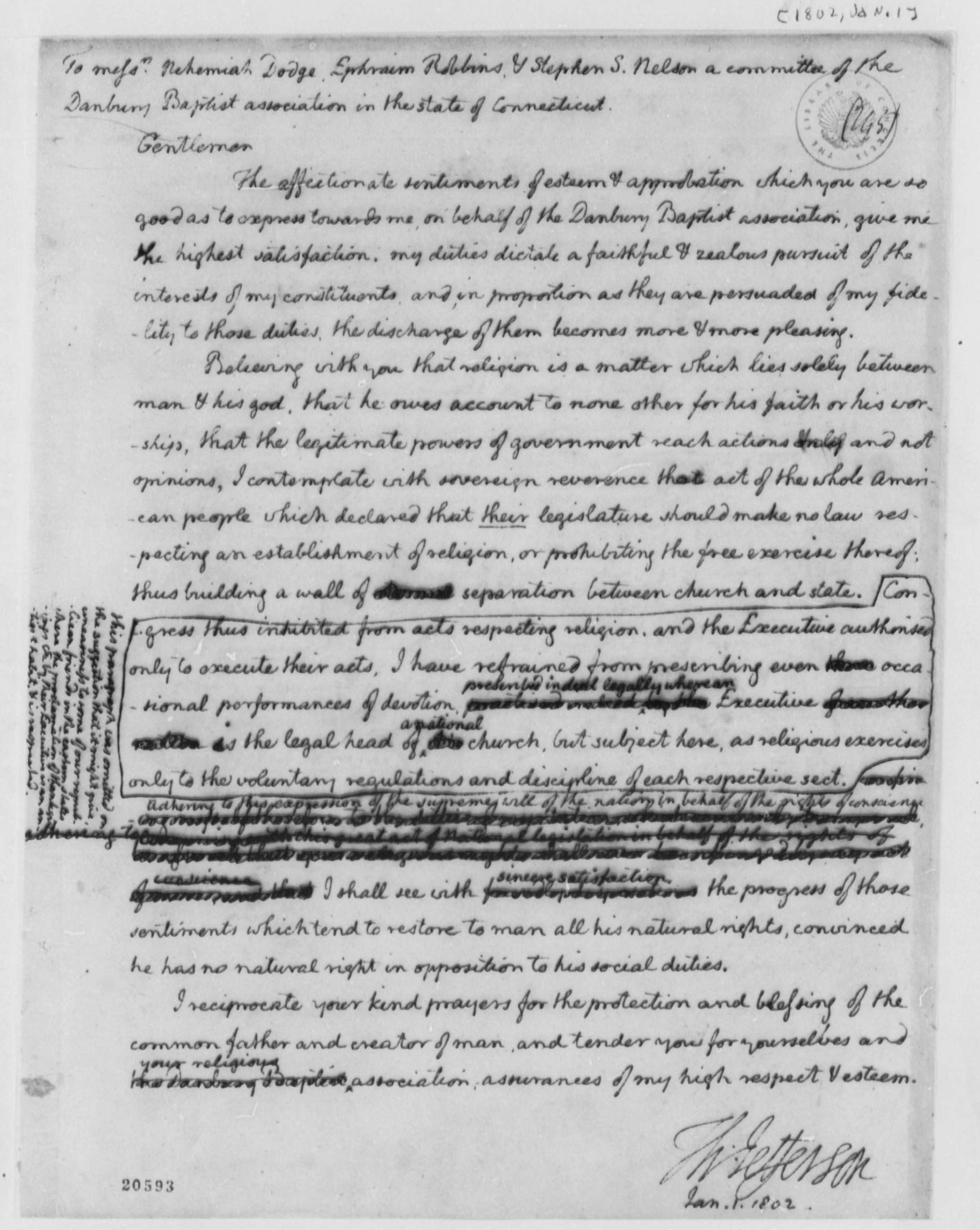

Thomas Jefferson Writes to the Baptists (Jan. 1, 1802)

After the acrimonious 1800 presidential election, Connecticut’s Danbury Baptist Association wrote to the new president, Thomas Jefferson, to ask him to declare a day of prayer and thanksgiving to heal the nation. In a written response, Jefferson politely declined, coining the phrase, “wall of separation between Church & State” to explain that the First Amendment prevented him from associating the presidency with a religious declaration. The letter — which drew on his firm belief that government support of any religion through tax revenue or otherwise was discriminatory — provides a pivotal moment in American religious freedom. It emphasized Jefferson’s separation of church and state at a time when not everyone agreed with that interpretation of the First Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court would eventually adopt Jefferson’s wall metaphor, first, in an 1878 case in which it ruled against polygamy and, next, in a 1947 decision defining more fully why the Constitution prohibits a breach of the wall between religion and government. Jefferson’s historic 1801 letter provides the foundation for avoiding religious Balkanization in the United States, allows for John F. Kennedy’s Jeffersonian rationale for why his Catholicism should not constitute a bar to his presidential election, and has served as a model of religious tolerance wherever it is embraced throughout the world.

Barbara A. Perry is Director of Presidential Studies and Co-Chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

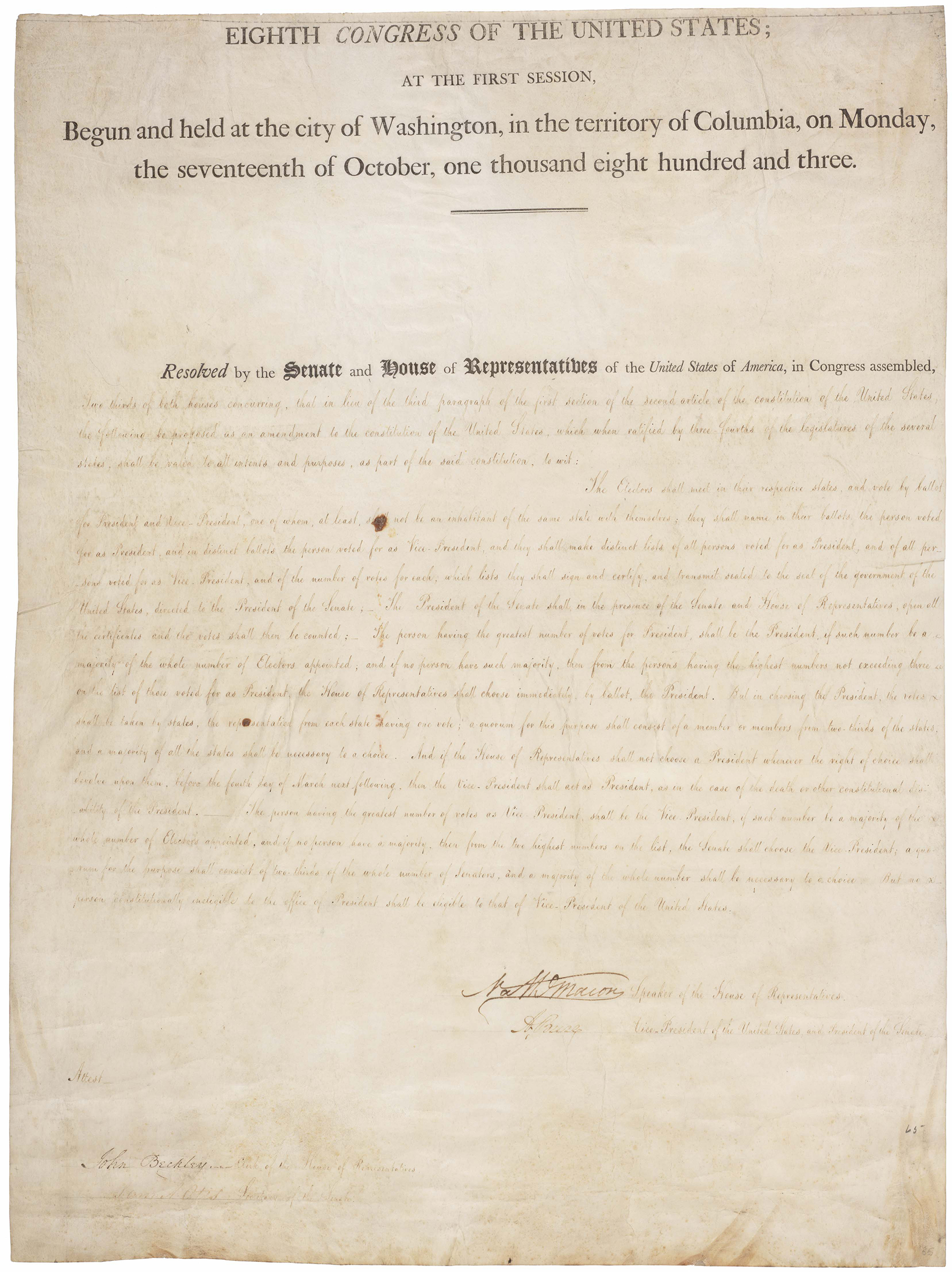

The 12th Amendment Is Ratified (June 15, 1804)

The people who framed the Constitution didn’t imagine any of the political party system that we’re in. The Constitution was set up so that the person who got the most votes was president and the person who got the second most was vice president, like the way a high school student council runs. That system worked fine when General Washington was elected, but after he stepped down it became obvious that it did not work very well. In 1796, you had people who ran from opposing parties — and basically couldn’t stand each other — become President and Vice President. In 1800 the election resulted in an even stranger situation, where two people from the same party ended up with the exact same number of votes. (The second act of Hamilton is about what happened next.) After Jefferson became President (instead of Aaron Burr), Congress decided to amend the Constitution, so that the electors would vote using distinct ballots for president and vice-president and to create a system for what to do if no one gets a majority . The result was a system in which a strong political party wins the entire executive branch. But for the 12th amendment, we wouldn’t have had the political parties, presidential elections, and presidents we have. We’d have President Trump and Vice-President Clinton.

Mary Sarah Bilder is Founders Professor of Law at the Boston College Law School and author of the Bancroft Prize-winning Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention.

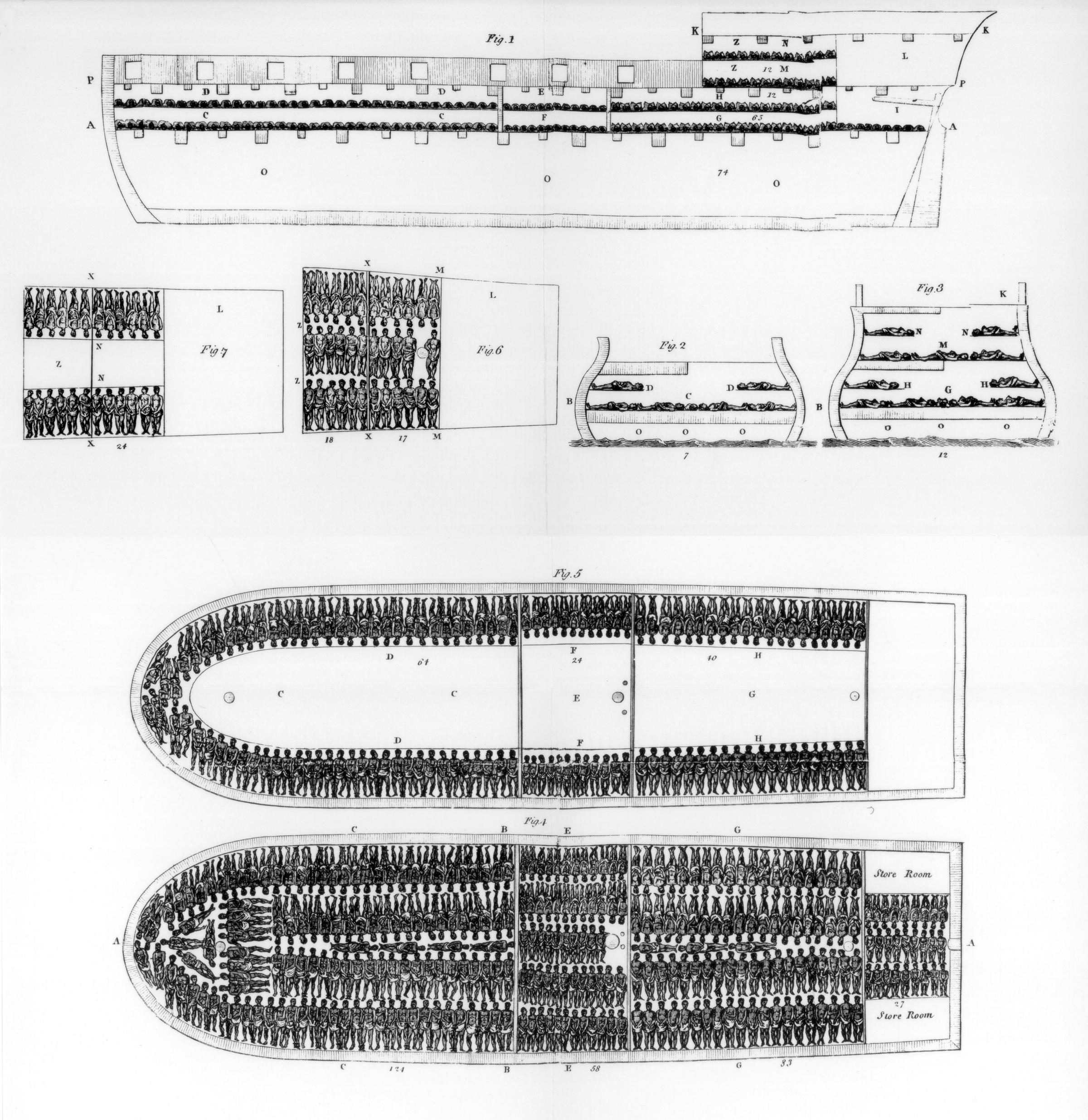

The Transatlantic Slave Trade Is Abolished (Jan. 1, 1808)

On March 2, 1807, the House of Representatives and Senate passed legislation “to Prohibit the importation of Slaves” into the United States. The law would close the traffic in human chattel imported from “any foreign kingdom, place, or country,” making the international trade in “any negro, mulatto, or person of colour with intent to hold, sell, or dispose . . . as a slave, or to be held to service or labour,” illegal. Yet, the demise of the slave trade was not the demise of slavery, nor was it the demise of slave trading on U.S. soil. As the young nation worked to solidify its independence, this moment instead signified the end of one era in slavery and the beginning of another. Traders shifted their focus to a growing domestic traffic that had been operating since the late-18th century. This legislation, along with new technologies (cotton gin), Westward expansion (Louisiana Purchase), and an emphasis on reproduction through forced breeding, actually fueled the institution of slavery. Three times the number of enslaved people experienced sale through the domestic trade (approximately 1 million souls) than those directly imported on slavers. However, despite this legislation, African “cargo” were illegally brought across the Atlantic until the eve of the Civil War.

Daina Ramey Berry is associate professor of History and African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas (Austin) and author of The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation.

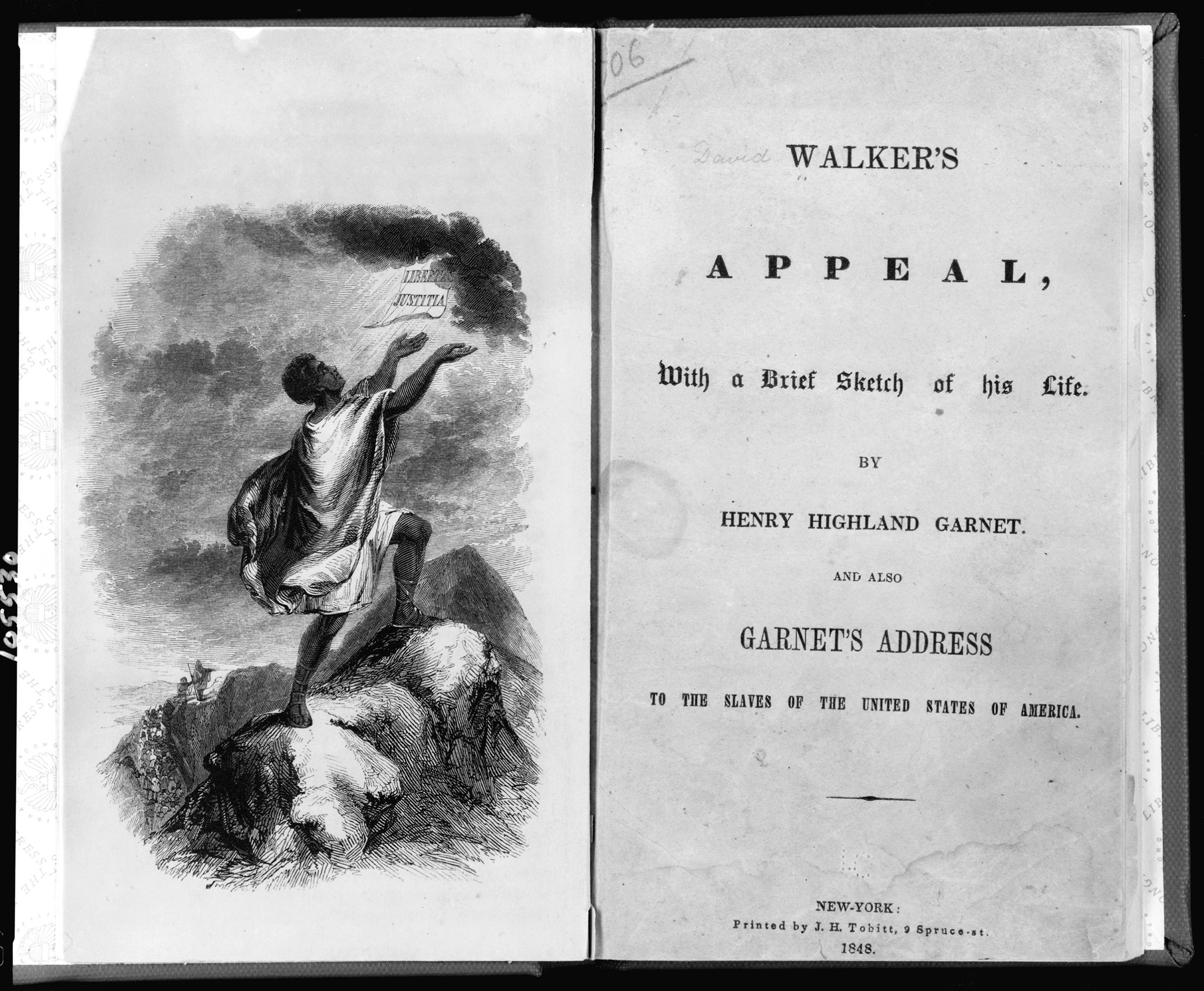

David Walker Writes His Appeal (Sept. 28, 1829)

Most people associate the rise of the radical antislavery movement in the United States with William Lloyd Garrison, a white reformer and journalist, but in fact, the origins of abolitionism lie in the free black community. In the late 1820s, David Walker emerged as the most eloquent spokesperson for those abolitionist activists who called for the immediate end of slavery. His Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829) criticized Americans for failing to live up to the ideals of Christianity and the Declaration of Independence and for what he regarded as the most brutal system of slavery in world history. Walker also called upon free African Americans to “uplift” themselves and to promote the cause of slaves through education and evangelical Christianity, and he predicted a race war if white Americans did not repent of the sins of slavery and racism. Before the emergence of abolitionism, many white leaders of the antislavery movement had promoted colonization—plans for a forced resettlement of free blacks in Africa. Walker forcefully rejected colonization schemes, arguing that blacks had as much right to full citizenship in the United States as did whites.

Christine Heyrman is Robert W. and Shirley P. Grimble Professor of American History at the University of Delaware and author of the Francis Parkman Prize-winning American Apostles: When Evangelicals Entered the World of Islam.

The First Issue of The Liberator Is Published (Jan. 1, 1831)

The Liberator set the world aflame. First published in 1831, the newspaper and its editor, William Lloyd Garrison, gave voice to a new type of abolitionism. Unlike earlier proponents of ending slavery, who had advocated a cautious approach, Garrison demanded the immediate and uncompensated emancipation of all enslaved people and full citizenship rights for black Americans. The Liberator provided a platform for black Northerners writing against slavery and racism, and Garrison’s radical critique of slavery, in turn, was deeply informed by the work of black writers and activists. From The Liberator emerged the American Anti-Slavery Society, a national organization that transformed abolition into a mass social movement. For nearly a century after emancipation, historians considered Garrison and The Liberator fringe, delusional and unimportant to the larger politics of the Civil War. But radical abolitionists pushed Southern politicians to adopt a more vigorous defense of slavery, eventually provoking a response from the North. The Liberator set the stage for a sea change in American politics that forced the sectional conflict over slavery to a head.

Justin Leroy is an assistant professor of history at the University of California, Davis, and a past winner of the Society of American Historians Allan Nevins Prize, for the best-written doctoral dissertation on a significant subject in American history.

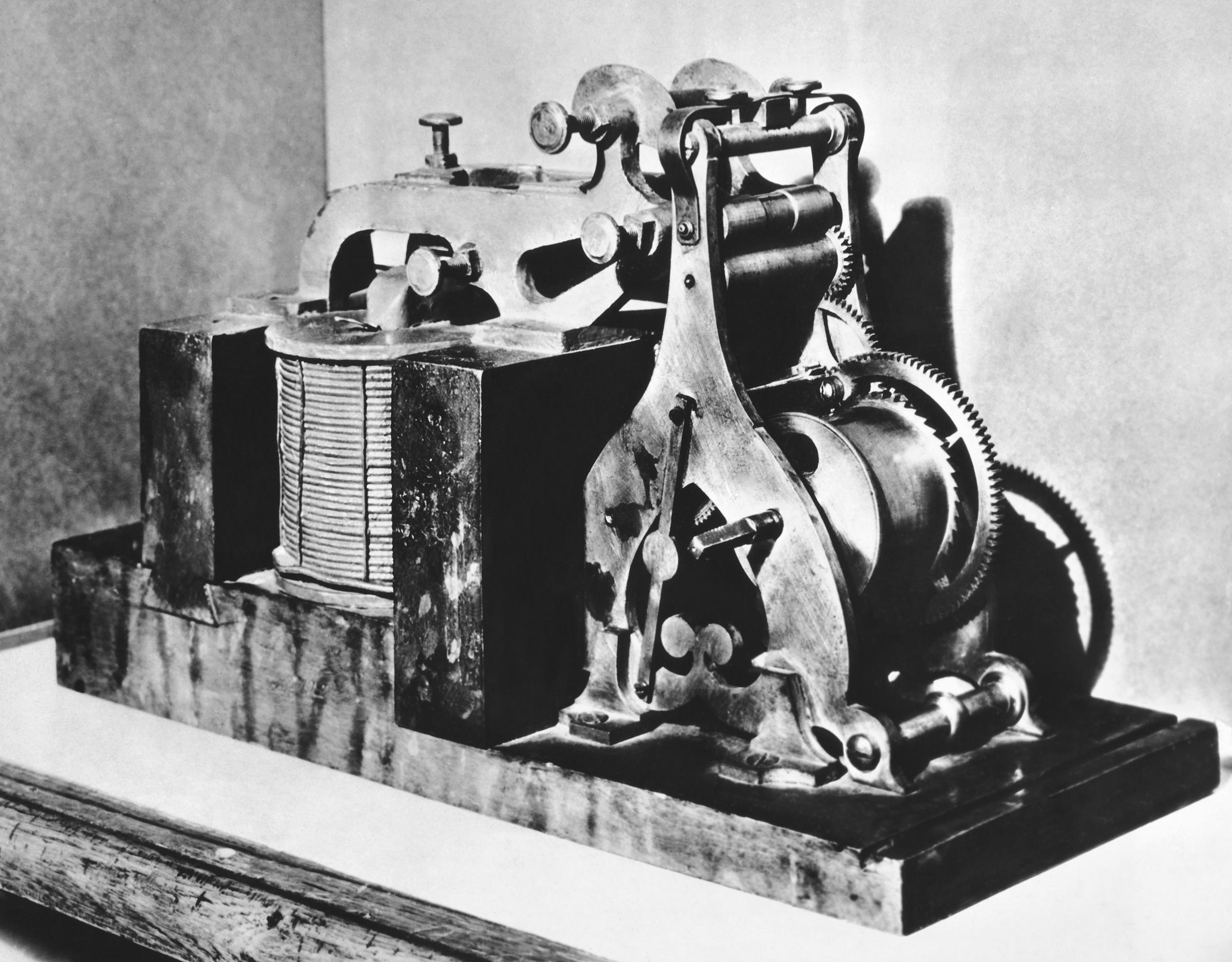

The First Electric Telegraph Message Is Sent (May 24, 1844)

By the 1840s, the electric telegraph was a long time coming. Optical telegraphs had been in operation for at least two generations and a series of scientific advancements had gradually created the technology needed for transmitting signals over electromagnetic wires. By the spring of 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse, a fine-arts professor turned scientist, was ready to inaugurate the system he had perfected with the aid of government funding. On May 24, he sent a four-word message over 40 miles of wire, from Washington to Baltimore, where his associate Alfred Vail received it and sent it back. The Old Testament verse Morse chose for the occasion, “What Hath God Wrought,” was fittingly dramatic. The electric telegraph was the first device to effectively separate communication from transportation, enabling information to travel instantly over space and catapulting America into the era of telecommunication. During the second half of the 19th century, it played a crucial role in unifying the country, tying together remote individuals, communities and markets into what became the modern United States.

Yael Sternhell is a professor at Tel Aviv University, author of Routes of War: The World of Movement in the Confederate South and the 2017 winner of the Organization of American Historians Binkley-Stephenson Award for the best article that appeared in the Journal of American History.

Britain Repeals Its Corn Laws (May 15, 1846)

The most important moment of the 19th century for the United States took place across the ocean: the Repeal of Britain’s Corn Laws. The Corn Laws were simply tariffs, or taxes, that Parliament imposed on foreign grain. Though the Earls of Grantham benefited when it came to selling English grain, the poor paid more for food. A British manufacturer named Richard Cobden argued that tariffs, by slowing commerce, impeded freedom. “The progress of freedom,” he said, had more to do with the spread of business than with the actions of governments. The laws were finally repealed in 1846, after the Irish Famine dramatized their injustice.

The repeal cracked England’s class structure. Once the tariff wall tumbled, others gradually weakened, including those holding back workers or women. Commerce begat freedom, just as Cobden predicted. Liberal, open Britain inspired others the world over. In the 1930s, a U.S. Secretary of State known as “Tennessee’s Cobden,” Cordell Hull, helped President Franklin Roosevelt break down high tariffs, reducing the Great Depression’s damage. After World War II, U.S. policy moved toward free trade. Today, the world’s stronger economies are more Cobden than Corn Law—all because of abolition of an English grain tariff.

Amity Shlaes’ bestselling books include Coolidge and The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression.

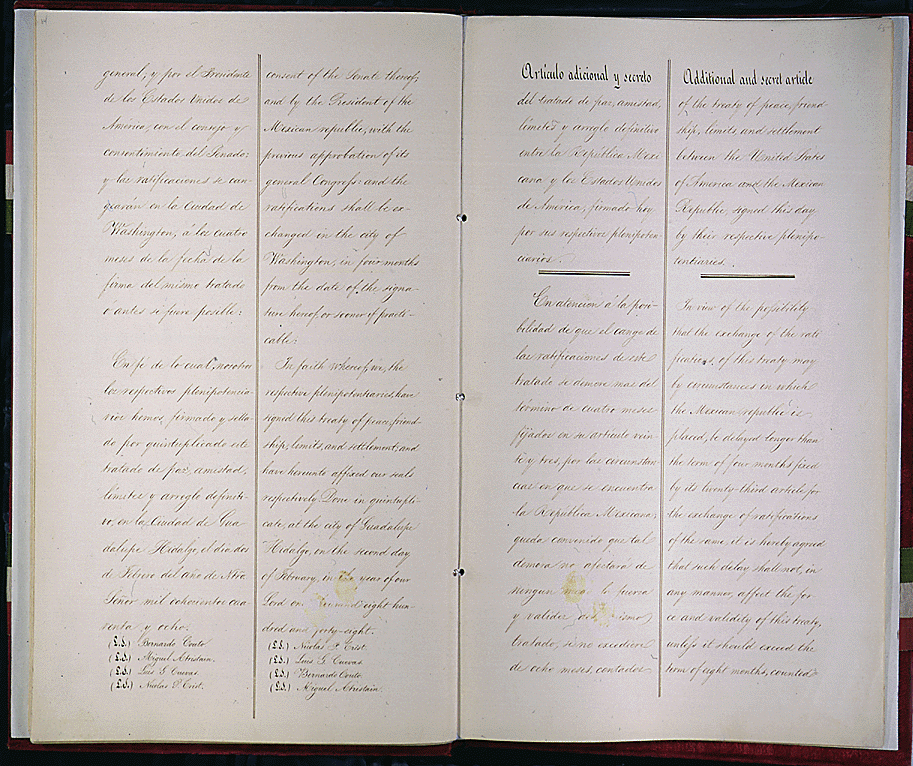

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Is Signed (Feb. 2, 1848)

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo brought to a close the war with Mexico, yet left in its wake unresolved dilemmas with lasting repercussions for American history. The U.S. expanded by a third, becoming a continental nation for the first time through the acquisition of such rich new territories as California, Arizona and New Mexico. Mexicans already residing on these lands became U.S. citizens, one of the first expansions of citizenship in American history, predating the granting of citizenship to African Americans or Native Americans. The treaty also lay the groundwork for future conflicts: the Civil War, triggered by increasingly furious debates about the expansion of slavery into the territory seized from Mexico; and the Indian Wars, caused in part by the new border slicing through Indian homelands. In Mexico, the war with their northern neighbors and the ensuing treaty loom large in popular consciousness. In the U.S., however, the Mexican-American War has been conveniently obscured — an embarrassingly naked land grab overshadowed by the drama of the subsequent Civil War. Yet the treaty created the border that (with minor modifications) has become such a flashpoint in American politics and it raised enduring questions about the status of peoples of Mexican descent in the U.S.

Karl Jacoby is a professor of history at Columbia University and author of the Ray Allen Billington Prize-winning The Strange Career of William Ellis: The Texas Slave Who Became a Mexican Millionaire.

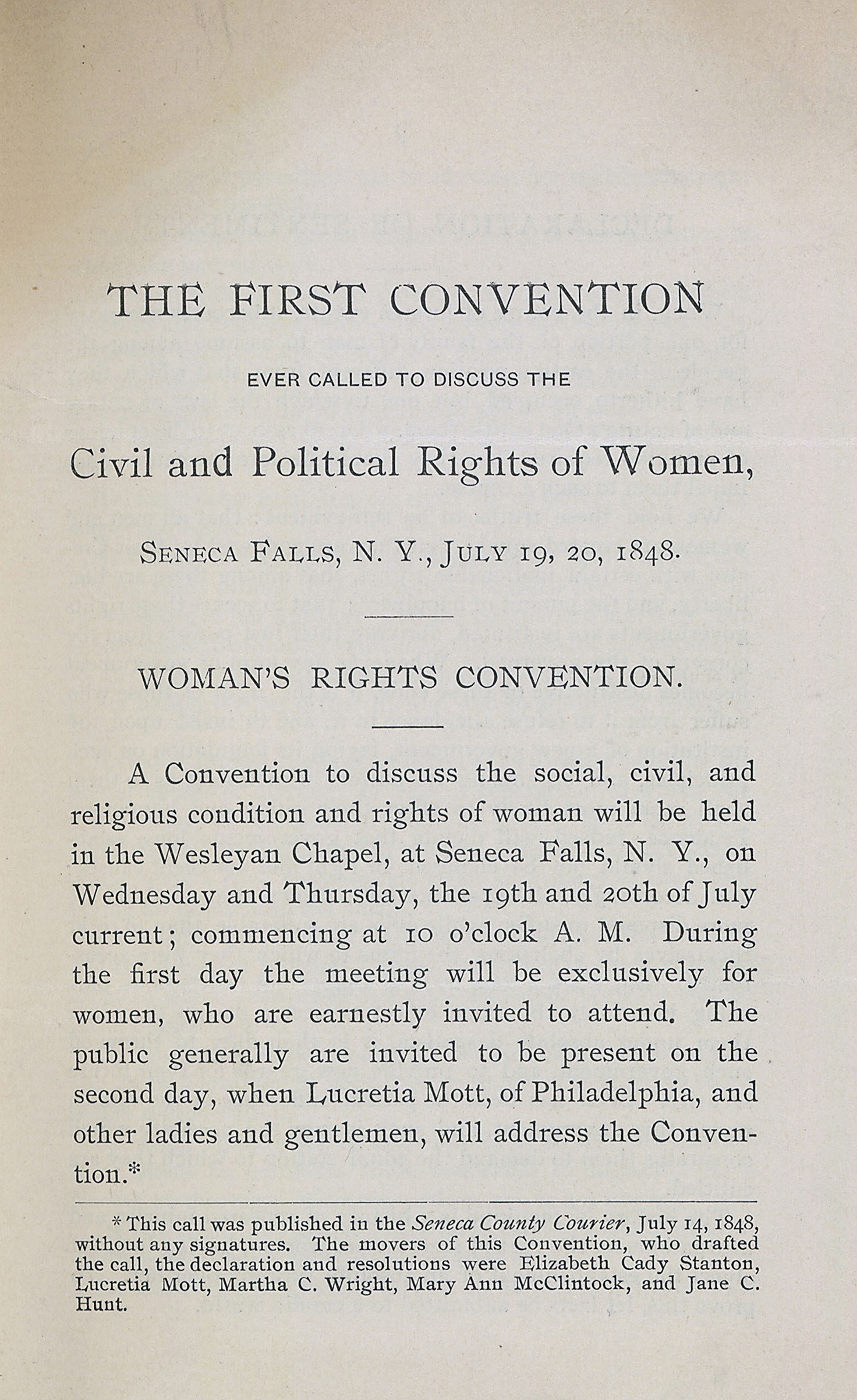

Women’s Rights Activists Meet in Seneca Falls, N.Y. (July 19, 1848)

In 1848, a handful of women activists, including Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, issued a call for a “Woman’s Right Convention,” in Seneca Falls, N.Y. Most attendees were politically active; Frederick Douglass participated. Perhaps the most important result of the meeting was embodied in “The Declaration of Sentiments,” a feminist document modeled on the Declaration of Independence. The authors asserted that “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” Signed by 68 women and 32 men, the document not only insisted on the still-radical idea that women are equal to men, but also that society rather than nature held women back. “The history of mankind,” the authors pointed out, “is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.” The Declaration of Sentiments also called for women to have the right to vote, something that would take another 72 years to accomplish. Women’s activists still cite the Declaration of Sentiments as a crucial statement in the long fight for women’s rights.

Wendy Warren is an assistant professor of history at Princeton University and the author of New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History.

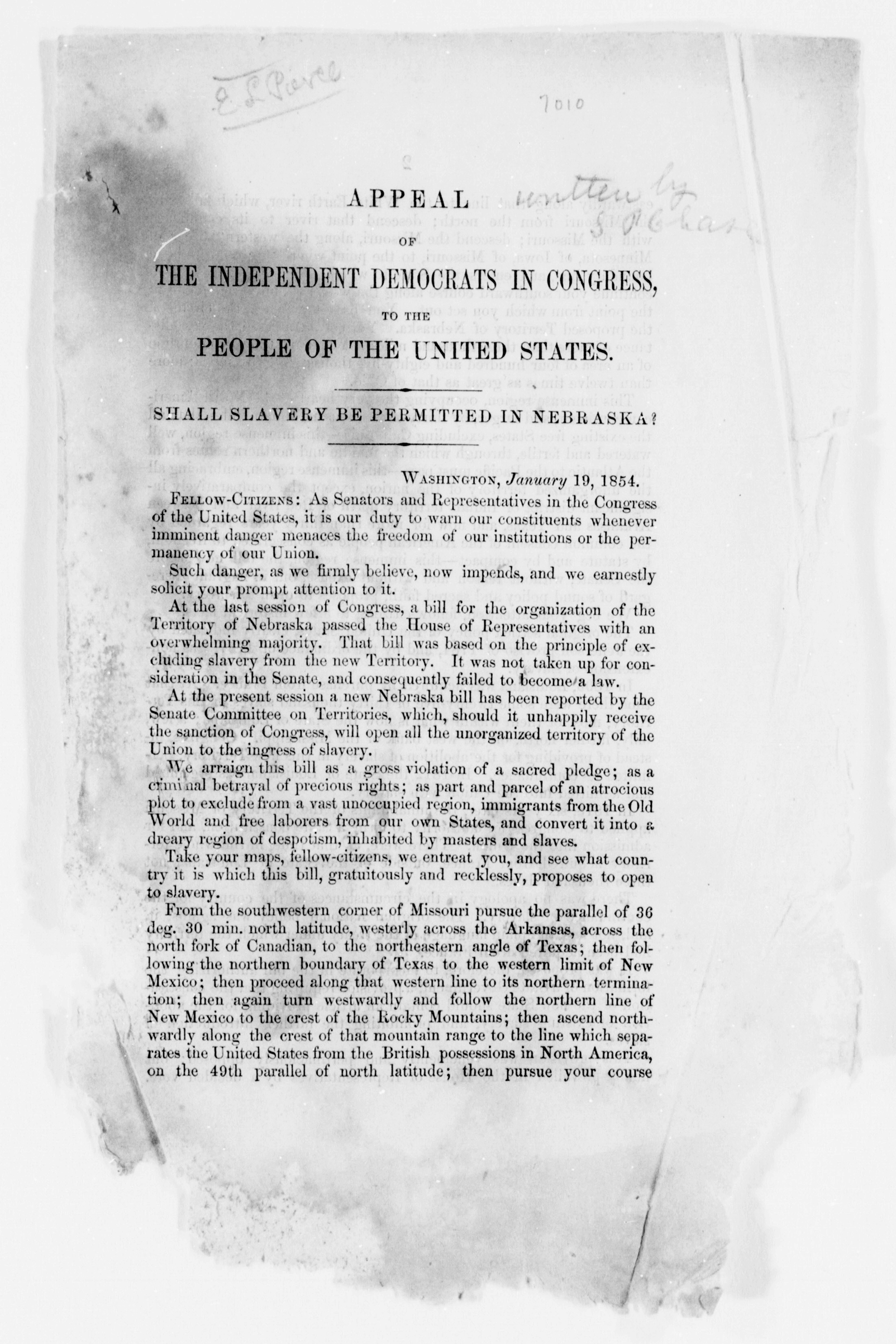

The “Appeal of the Independent Democrats” Helps Launch the Republican Party (Jan. 19, 1854)

In January 1854, when Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas introduced his bill to organize the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, he admitted privately that it would “raise a hell of a storm.” Many in the North were sure to be outraged at the bill’s repeal of the Missouri Compromise ban on territorial slavery above the 36°30′ parallel. But how long would the storm last? Led by Ohio Senator Salmon Chase, a handful of antislavery leaders in Washington were determined to make the most of it. Their manifesto, “The Appeal of the Independent Democrats,” declared that the Kansas-Nebraska bill was part of an “atrocious plot” to convert the entire West “into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves.” A masterpiece of propaganda, the “Appeal” circulated widely, channeling Northern outrage away from a narrow defense of the old Missouri Compromise, and toward a much stronger commitment to oppose any extension of slavery whatsoever. Within a year, that commitment became the basis of the new Republican Party, whose uncompromising antislavery stand revolutionized American politics for good.

Matthew Karp is an assistant professor of history at Princeton University, author of This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy and a recipient of an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellowship from the New-York Historical Society.

The U.S. Army Marches Into Salt Lake City (June 26, 1858)

On June 26, 1858, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston and 2,500 troops marched into an eerily quiet Salt Lake City. President James Buchanan had ordered Johnston to take the Utah capital, which had been settled by the Mormons (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints). Meanwhile, an orderly evacuation allowed 30,000 Mormons to hide in southern Utah. Having been burned out of Missouri in 1838 and Illinois in 1846, and having kept the U.S. troops away from their city during the 1857-1858 winter, the Mormons knew when to back down. U.S. troops had never before marched on their own citizens. Many Americans hated Mormons because of polygamy, but the U.S. Army traveled 1,000 miles and wintered in the Utah mountains for a different reason: Mormons had defied federal law. When Brigham Young, Mormon leader and first Territorial Governor, refused to give his position to a non-Mormon appointed governor, President Buchanan called it rebellion. A defiant state controlled by church officials, even if those leaders had been elected, could not be tolerated. In an era when the U.S. Army removed Native Americans to open land for white citizens, the federal government demonstrated how far it would go to determine who governed the West and how.

Anne Hyde is a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma, editor of the Western Historical Quarterly, and author of Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West, 1800-1860, which was a Bancroft Prize winner and Pulitzer Prize finalist.

The Emancipation Proclamation Is Issued (Jan. 1, 1863)

The Emancipation Proclamation, which was issued by Abraham Lincoln in the midst of Civil War, freed all the slaves in the Confederacy and invited black men to enlist in the Union Army. Even though it was applicable to only those states that were in rebellion against the United States government, it sounded the death knell of slavery in the American republic. An overwhelming majority of American slaves were declared free by it. Lincoln called it the “pivotal act” of his administration and the greatest event of the 19th century. The Proclamation laid the foundation for the ongoing transformation of the United States from a slaveholding nation into an interracial democracy. It marked not just an end to the enslavement of African Americans but also signaled at black citizenship by asking former slaves to join the Union Army. In this sense, it was a precursor to the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, which remade the U.S. Constitution by abolishing slavery and establishing national birthright citizenship, equality before the law and voting rights for black men.

Manisha Sinha is the Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut and author of The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, which won the Avery O. Craven prize for the best book on the Civil War era.

Correction: The original version of this item misstated the date on which the final Emancipation Proclamation was issued. It was Jan. 1, 1863, not Sept. 22, 1862.

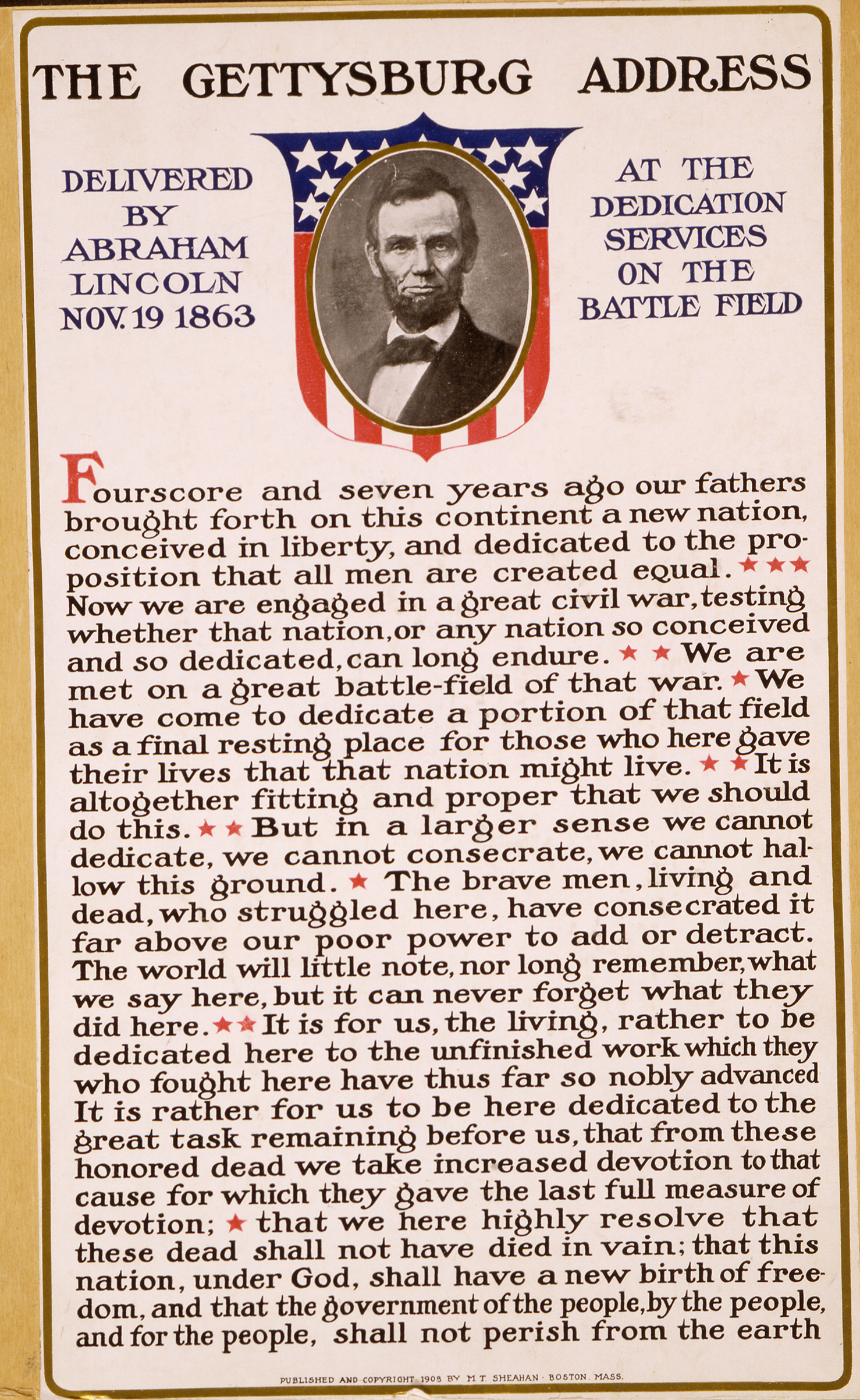

Abraham Lincoln Delivers the Gettysburg Address (Nov. 19, 1863)

Gettysburg is the site of the greatest battle fought in North America, the decisive turning point in the greatest event in American history, and the place that prompted the greatest speech in the English language. President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered on Nov. 19, 1863, is a reflection in many ways on what came before and what was to come, creating a new vision for the country focused on equality and self government. Many of the great movements to come are anchored in Lincoln’s words, which amounted to a new operating system for a newly reborn republic: that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Ken Burns is an Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker and the co-director with Lynn Novick of The Vietnam War, which will air on PBS in September.

The 13th Amendment Is Ratified (Dec. 6, 1865)

By the time we get to 1865 and the passage of the 13th Amendment, which in effect formally abolished slavery in the United States, we’d had almost 250 years during which people of African descent as well as many Native peoples were enslaved in the U.S. Most people don’t realize that the debate over the Amendment began before the end of the Civil War. It was first debated on the Senate floor in March of 1864, but did not garner the necessary majority that was needed to pass as a constitutional amendment. That December, President Lincoln would say in his message to Congress that he hoped it would come up again — and in fact it did, in January of 1865, resulting in a vote where the House passed the amendment. (Lincoln was there to sign the proposed Amendment but would be assassinated before it was ratified.) The 13th Amendment signaled a significant movement forward for the nation as we wrestled with what it means to transition from slavery to freedom, not just for those of African descent but also for all Americans.

Earl Lewis is President of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and President-Elect of the Organization of American Historians.

The Supreme Court Decides Henderson v. Mayor of City of New York (Oct. 1, 1875)

The issue in this U.S. Supreme Court case was the question of who had authority over immigration control. Until the 1870s, state governments — not the federal government — were the primary administrators of immigration control. Northeastern states in particular restricted the immigration of indigent Europeans by requiring shipmasters to pay bonds and capitation taxes for the landing of such foreigners. Henderson declared such a practice unconstitutional for infringing on federal power over foreign commerce. This ruling triggered the emergence of federal immigration policy, as officials in states affected by the ruling campaigned for a national policy that would control immigration in place of invalidated state laws. The result of that campaign was the passage of the federal Immigration Act of 1882, America’s first national legislation to regulate general immigration. The act prohibited the admission of people unable to financially support themselves, such as paupers and lunatics, and criminals. This act bridged the eras of state-level and federal immigration control, laying the foundation for subsequent national immigration policy. Even now, as the relationship between the federal government and states over immigration policy is hotly contested, the root of the present debate can be found in Henderson.

Hidetaka Hirota teaches history at the City College of New York and is the author of Expelling the Poor.

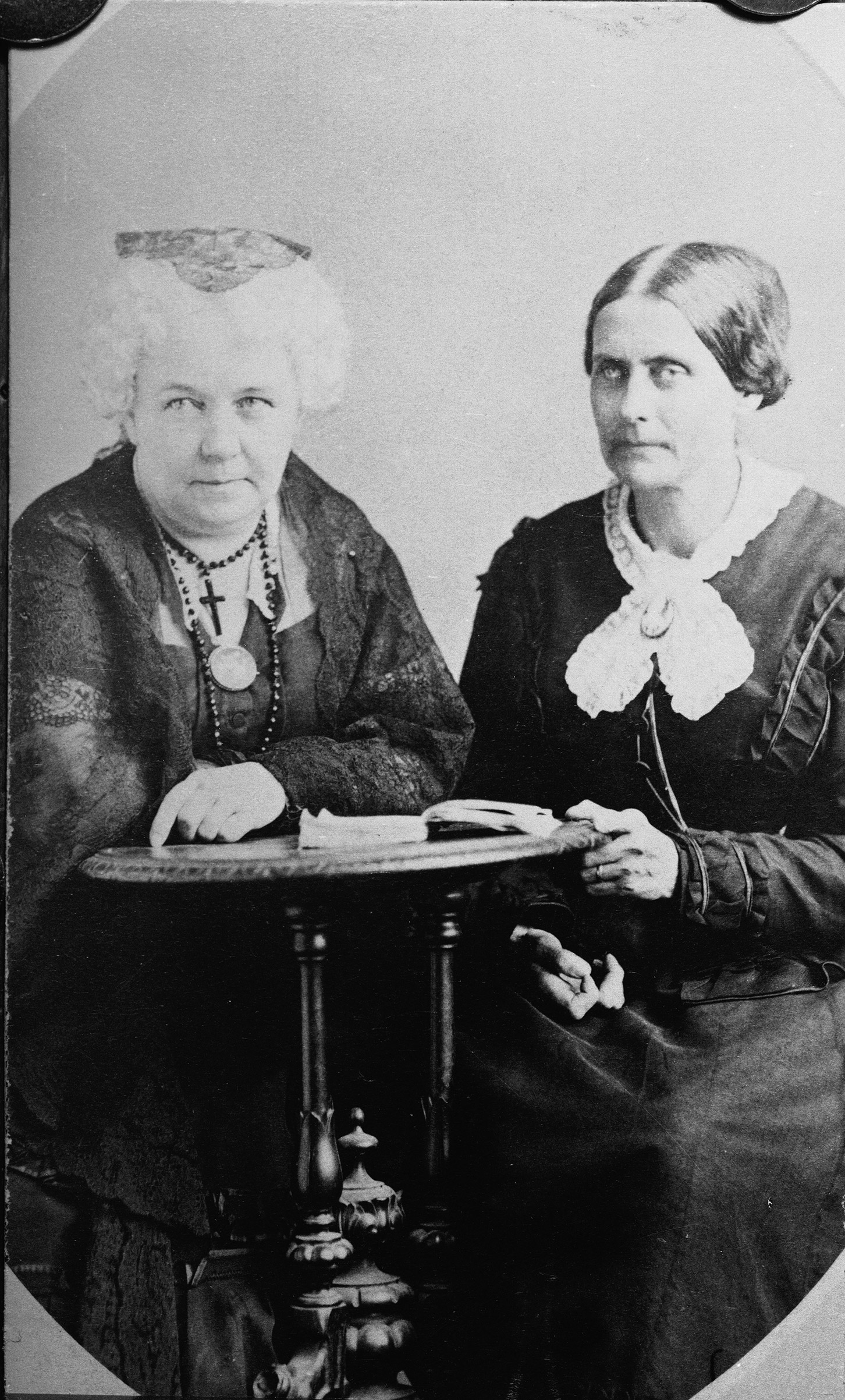

Susan B. Anthony Speaks at the Centennial (July 4, 1876)

In 1876, Susan B. Anthony was barred from delivering a speech at the centennial celebration of American independence at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Rather than give up, she and her compatriots distributed printed copies to the audience and then went around the back of the hall, where Anthony read it to a crowd. In this amazing manifesto, written with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the National Woman Suffrage Association, she called for the impeachment of all officers of the federal government, on the grounds that they had not been true to the promises of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Women were taxed without representation. And, because women did not serve on juries, they were not judged by their peers. The speech made little splash at the time, but when we read it today, we can see that there’s an anger in it. These women had fought for the vote for decades, but when the franchise was expanded in the 1860s, they were still excluded. They realized that begging was not going to get them anywhere. From that point on, they speak in a different voice — and that struggle goes on. When we look at it, we can see the agenda of the 1970s in the agenda of the 1870s.

Linda K. Kerber is May Brodbeck Professor in the Liberal Arts and Professor of History Emerita at the University of Iowa, and a past president of both the American Historical Association and the Organization of American Historians.

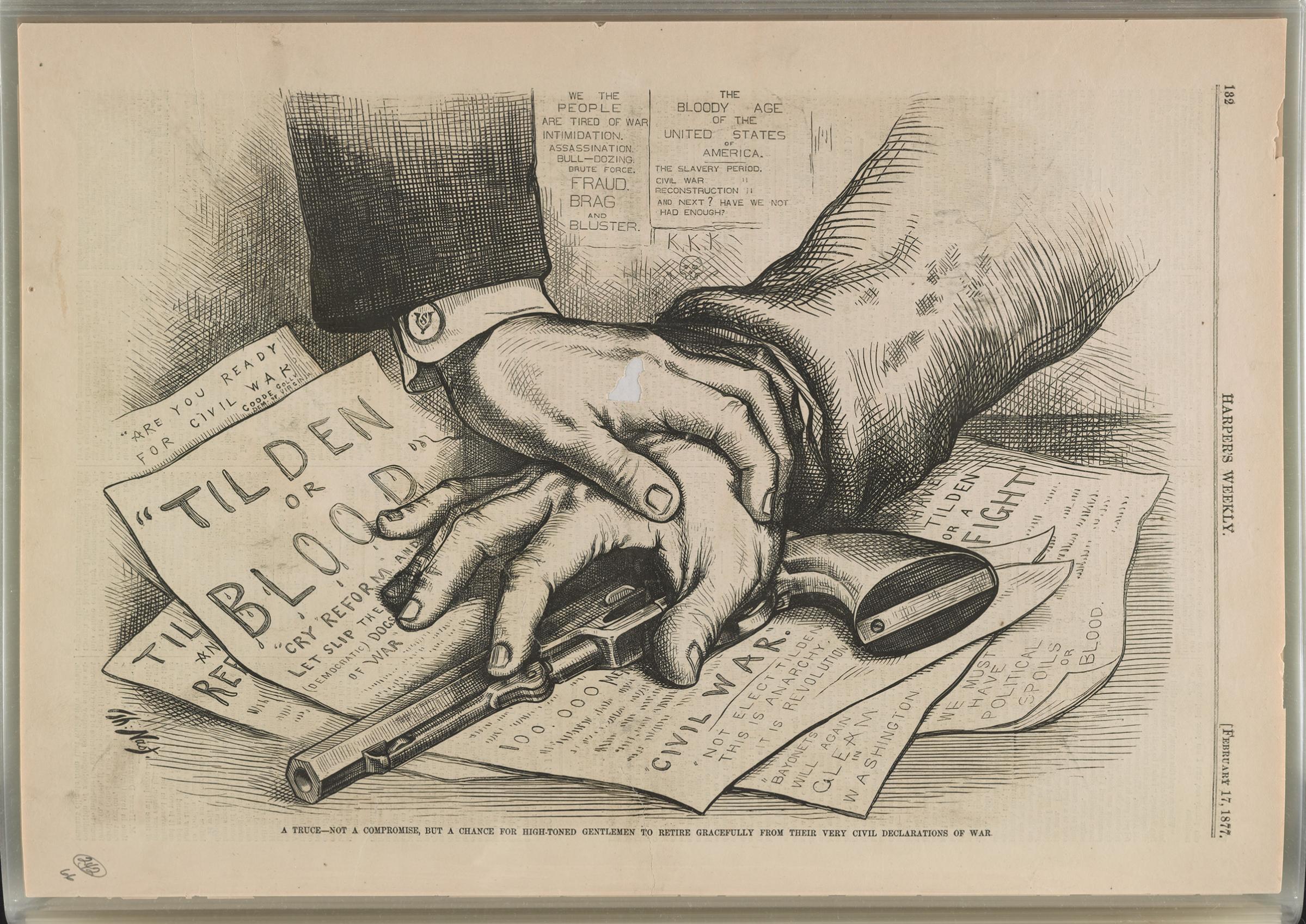

The Compromise of 1877 Is Reached (Mar. 2, 1877)

Following the Civil War, Reconstruction had offered the promise of social and political equality for the millions of African-Americans who began to vote, pursue education and participate in the political process. That hope was dashed after the election of 1876, when Republican presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes fell short on critical southern electoral votes. With the precise results of the election disputed, it was up a newly generated Electoral Commission (and, ultimately, Congress) to decide whether Hayes or his opponent, Samuel J. Tilden, would be president. Hayes did eventually secure the White House, but the terms of the compromise that got him there would end the period of congressional Reconstruction, reducing Washington’s power to intervene in state affairs. Federal troops were removed from the South, allowing southern legislatures and polling districts to return to their pre-Civil War, white supremacist practices. A new era of racist policy arose to continue the long-standing tradition of the degradation of black lives. The Compromise of 1877 ultimately led to a new era of Jim Crow laws, the effects of which would be felt for another century.

Michael Williams, of Warren New Tech High School is the 2017 winner of the Tachau Teacher of the Year Award from the Organization of American Historians.

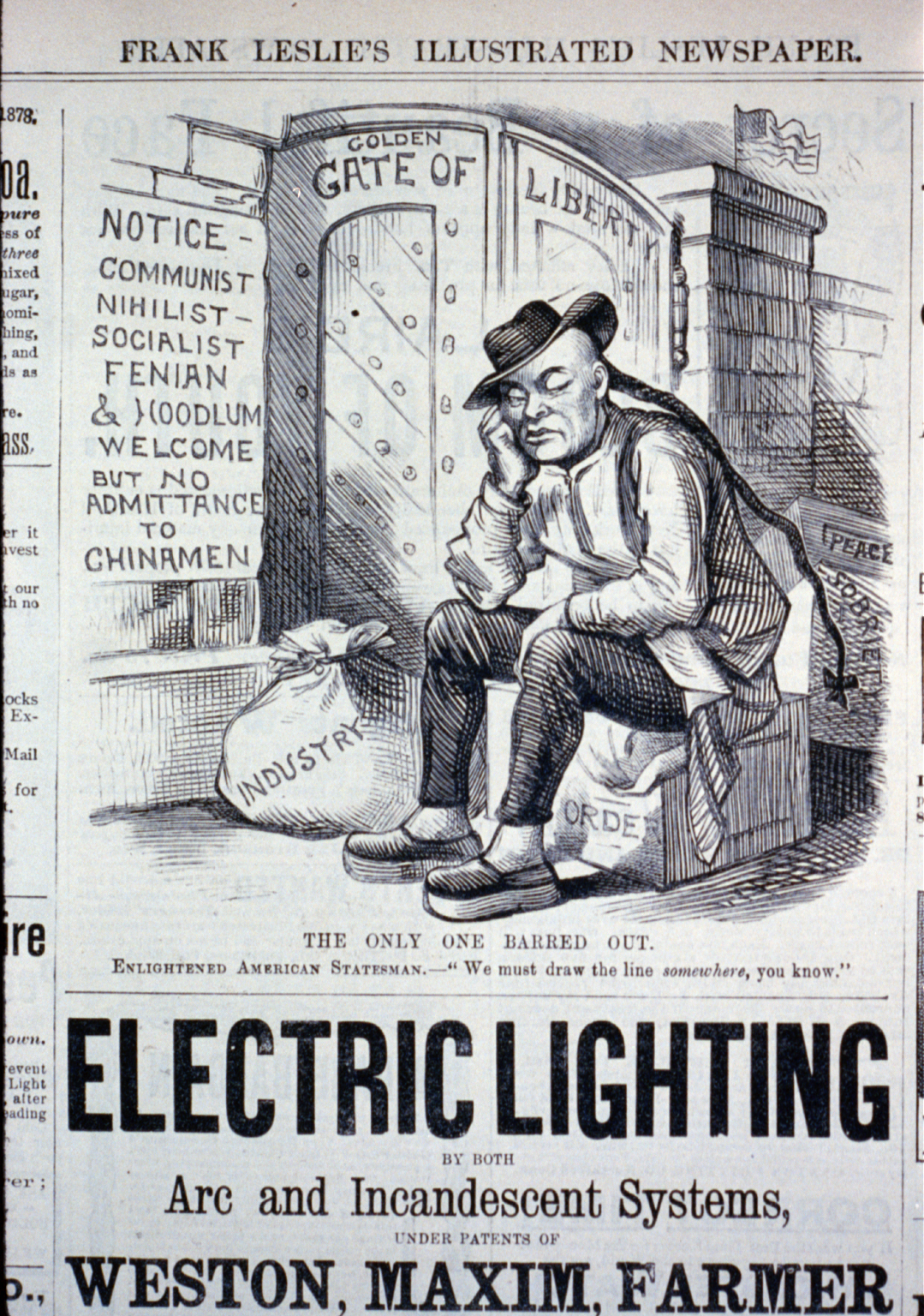

The Chinese Exclusion Act Is Approved (May 6, 1882)

On May 6, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act. The exclusion law resulted from two decades of racist agitation on the Pacific Coast by whites, who claimed the Chinese were a degraded, slave-like race. The law, which barred Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. and all Chinese from naturalized citizenship, imposed myriad harms on Chinese people. For those already living in the U.S., it meant decades of family separation, anti-miscegenation and other segregation laws, and racist violence.

Congress repealed the exclusion law during World War II, and in 2012 Congress passed a “resolution of regret.” But exclusion has still had long lasting consequences. Racist stereotypes about Chinese people as “unassimilable” persist — and, more broadly, Chinese exclusion set the legal basis for modern American immigration law. To justify discrimination against the Chinese, the Supreme Court ruled in 1889 that immigration was a matter of national security. That decision, which gave Congress nearly unlimited power over the regulation of immigration, remains the basic structure of our immigration system.

Mae Ngai is Lung Family Professor of Asian American Studies and Professor of History at Columbia University and author of the Frederick Jackson Turner Prize-winning Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America.

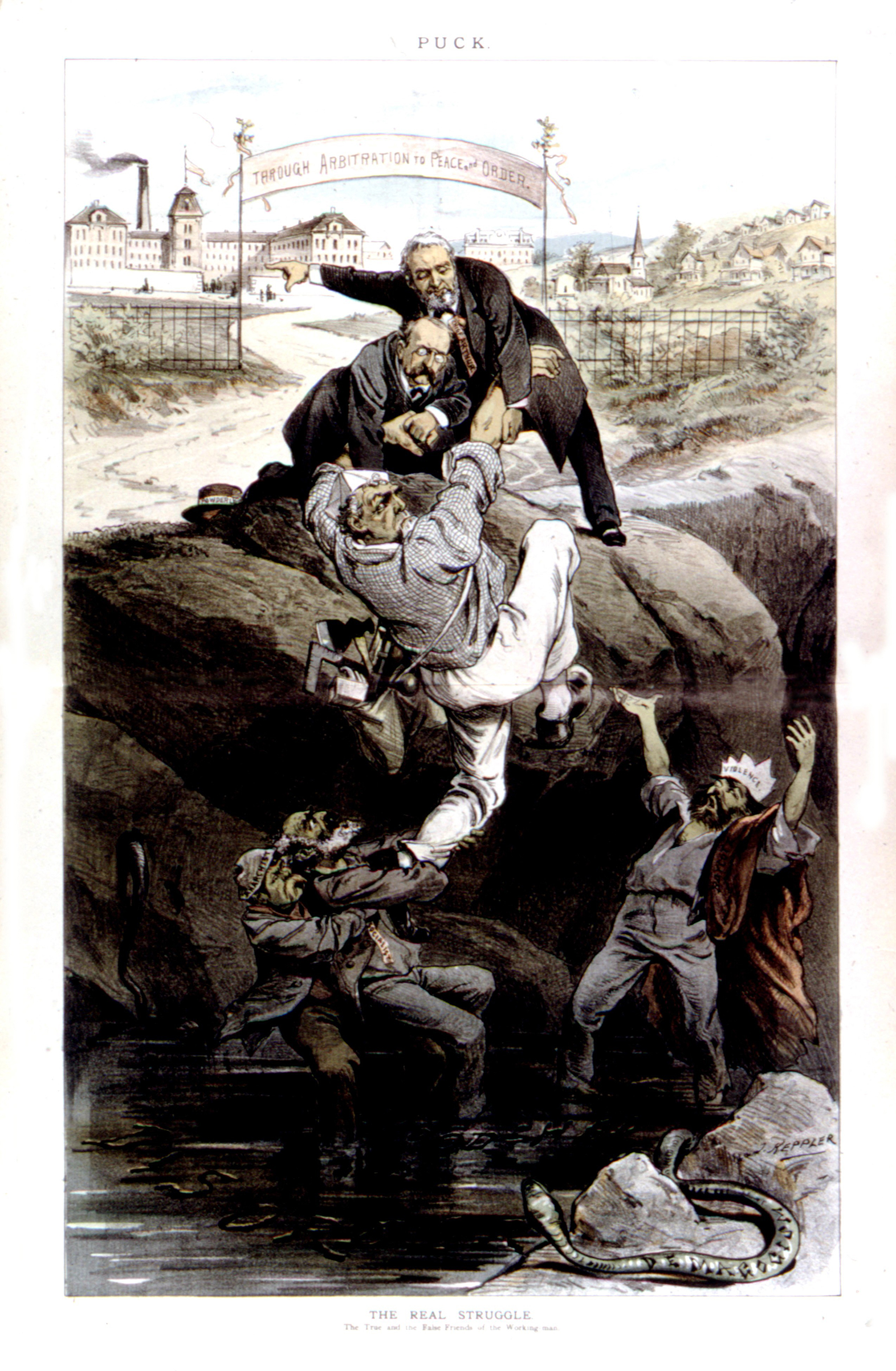

Workers Strike for an Eight-Hour Day (May 1, 1886)

On May 1, 1886, 350,000 workers from coast to coast joined in a coordinated general strike for the eight-hour day. The labor movement, which had grown in response to rapidly increasing inequality during the heyday of American industrialization, demanded that workers share in the great prosperity of the nation. Chicago was the center of these mobilizations, with at least 40,000 workers on strike that day. A coordinated response by employers and police forces defeated the movement at the time, yet over the next decades, American unions succeeded in improving wages and conditions for many workers, helping to build the middle-class society that was a hallmark of the United States. The movement also helped inspire the adoption of May Day as international workers’ day. Today, for the majority of the world, May Day is a public holiday; by 1990, it was celebrated in 107 states, prompting a historian to argue that it is “perhaps the only unquestionable dent made by a secular movement in the Christian or any other official calendar.” Unbeknownst to most, it originated in the United States, one of the few countries in the world where it is not widely celebrated and not a public holiday.

Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of History at Harvard University and author of the Bancroft Prize-winning Empire of Cotton: A Global History, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Hawaii Is Occupied (Jan. 17, 1893)

The occupation of Hawaii ended the existence of an independent state and launched for the U.S. the involvement in annexation of territory beyond the mainland. By the 1820s, missionaries and sugar planters had started arriving in the Kingdom of Hawaii from all over, and the American influence there grew. In 1887, the year the U.S. leased Pearl Harbor, the planters forced the adoption of a document known as the Bayonet Constitution, limiting the monarchy’s power. When Queen Liliuokalani attempted to replace it in 1893, the sugar planters organized a coup. One thing to note about the timing of the rebellion was that an 1890 law in the U.S., called the McKinley Tariff, meant that planters had a harder time getting Hawaiian sugar into the states. One solution for them was to make Hawaii an American territory. However, it would take years to approve the annexation, which didn’t happen until 1898, when the campaign for war with the Spanish had begun and Hawaii became appealing as a mid-Pacific fueling station. The case for annexation was not a slam dunk. That it succeeded shows a shift in American readiness to become involved in international politics more actively.

Patrick Manning is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of World History, Emeritus, at the University of Pittsburgh and a past president of the American Historical Association.

Coxey’s Army Arrives at the U.S. Capitol (May 1, 1894)

In the spring of 1894, unemployed workers from across the country marched on Washington. On May 1, Jacob Coxey, a Populist leader from Ohio, led marchers up to the steps of the Capitol to petition for a “good roads” bill that would put the unemployed to work. Before he could read his petition, Coxey was arrested for “stepping on the grass.” But the march still changed America’s politics of economic hardship. It did not scapegoat immigrants or minorities as previous protests had done, and was warmly greeted by immigrants in the mill towns and by Washington’s black community. It started the tradition of marches on Washington for economic justice and equal rights, which led most famously to the 1963 March for Jobs and Freedom at which Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I have a dream” speech. Finally, it placed on the national agenda that the federal government has a responsibility for the well-being of all citizens, including the poor and most vulnerable. In recognition of this principle, on May 1, 1944, Coxey was invited by Congress to read his petition on the steps of the Capitol, 50 years after his first attempt.

Charles Postel, professor of history at San Francisco State University, is the author of the Bancroft Prize- and Frederick Jackson Turner-winning The Populist Vision.

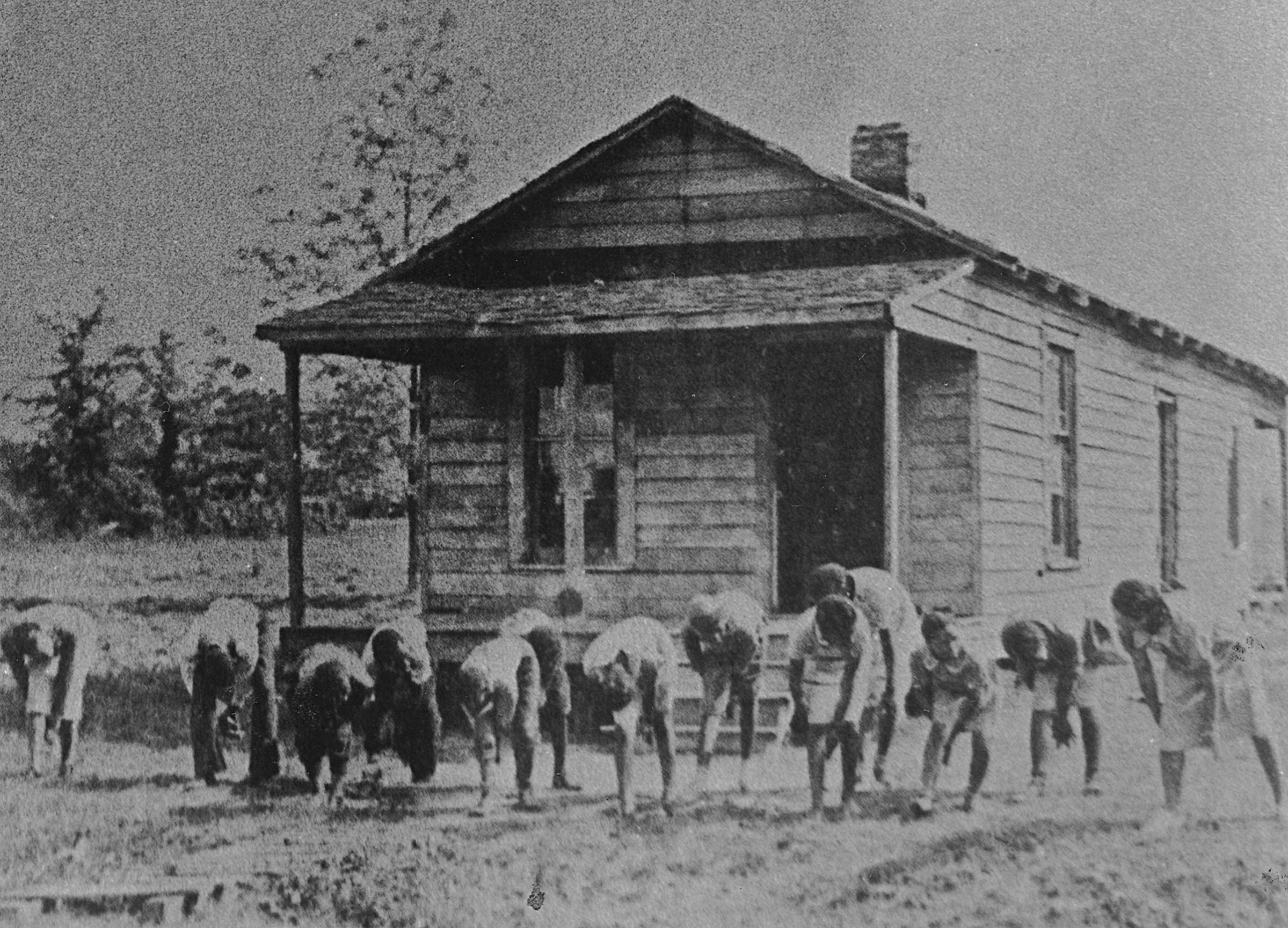

The Supreme Court Decides Plessy v. Ferguson (May 18, 1896)

On May 18, 1896, the Supreme Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson, a case that segregated the South and other parts of the nation for 68 years. It doomed many southern African Americans to three generations of inferior education, derelict housing and stunted economic opportunity. The court ruled that “separate” treatment of blacks and whites under the law was constitutional, as long as that treatment was “equal” — even though the 14th Amendment, which made freed people citizens, prohibited “any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens.” Although no southern state upheld the decision’s “equal” qualification, all passed laws to segregate black citizens.

It wasn’t supposed to turn out this way. Faced with an 1890 state law ordering segregation on trains, citizens of color in New Orleans had mounted a test case against it. Those who had so recently won full citizenship believed it improbable that their rights could be snatched away, and expected a victory. But Plessy v. Ferguson remained federal law until Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The long shadow of Plessy reminds us that progress is not inevitable, and that wrongs may take generations to right.

Glenda Gilmore is the Peter V. and C. Vann Woodward Professor of History at Yale. With Thomas Sugrue, she is author of These United States: A Nation in the Making, 1890 to the Present.

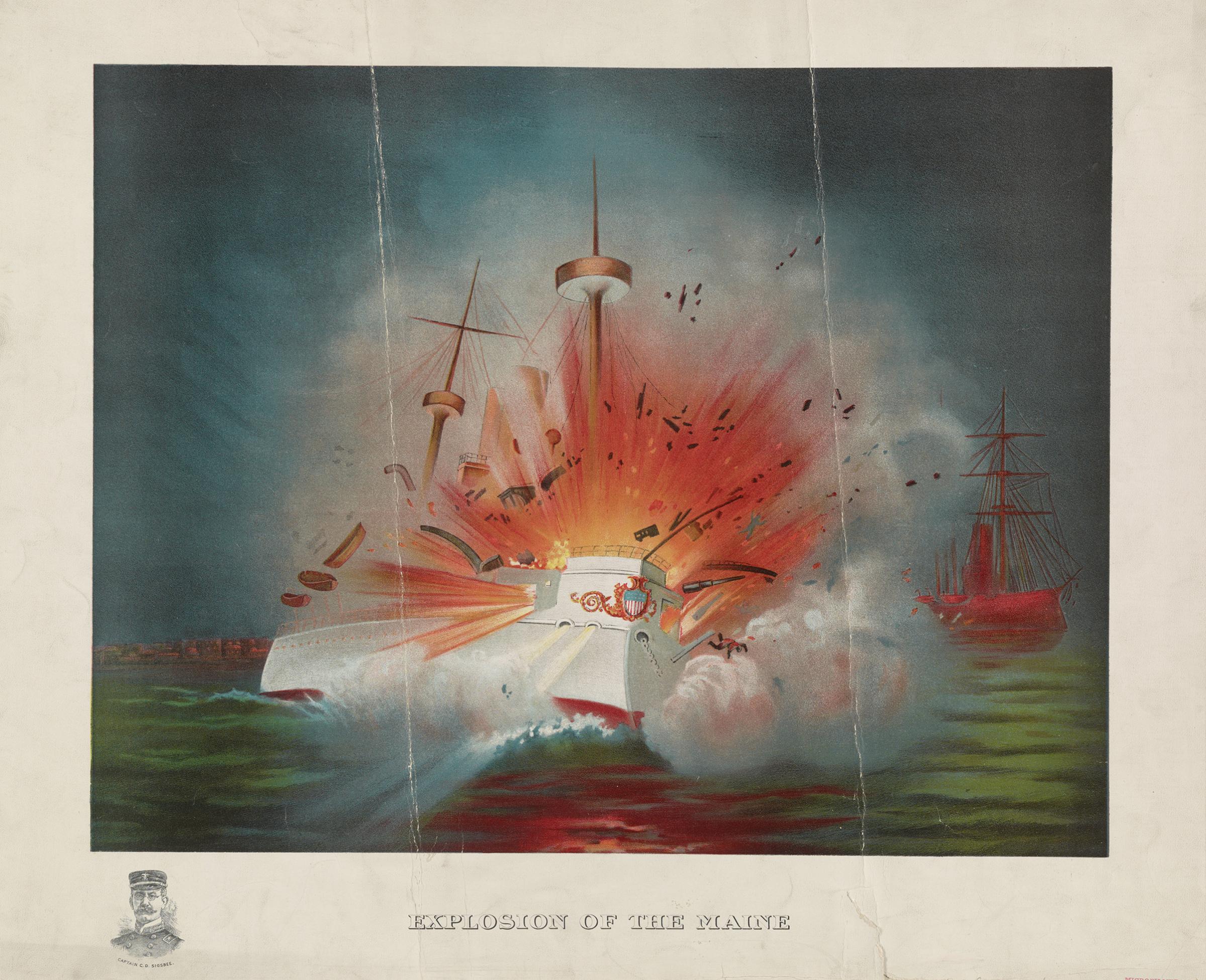

The USS Maine Is Sunk (Feb. 15, 1898)

In early 1898, as war raged in Cuba, the USS Maine docked in Havana’s harbor to signal to Spanish colonial authorities that the United States would protect its citizens and financial interests on the island if threatened. At 9:40 p.m. on Feb. 15, an explosion destroyed the ship, killing 268 American servicemen. The cause of the explosion was never conclusively determined, but Americans, goaded by the “yellow journalism” of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, blamed the fatalities on Spain and demanded retribution. Two months after the explosion, Congress issued a joint resolution authorizing military intervention. American participation in the “splendid little war,” as Secretary of State John Hay called the conflict, lasted four months, but had significant consequences for all. Spain lost what remained of its once vast colonial empire and the United States, in turn, acquired Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. U.S. economic interests in the Pacific and the Caribbean expanded as a result of these territorial acquisitions, but not before drawing Americans into a longer and costlier war in the Philippines (1899-1902). The “Spanish-American war” also had consequences for Spain’s former colonies, postponing or undermining their sovereignty.

María Cristina García is Howard A. Newman Professor of American Studies at Cornell and a 2016 Andrew Carnegie Fellow.

The Philippine-American War Begins (June 2, 1899)

A seminal but largely forgotten event in our history, the Philippine-American War gave rise to a fierce debate about America’s role in the world that is still as relevant today as it was 100 years ago. After a quick and decisive victory over Spanish forces in 1898, the U.S. decided to annex the Spanish colony of the Philippines, provoking nationalist fervor and a determined guerrilla resistance among the populace. Halfway around the world, American troops were soon mired in a bloody and brutal counterinsurgency. The military’s tactics – burning villages, torturing villagers, depriving civilians of food and medical supplies – alienated the local population and horrified the American public back home. Though the United States would declare victory in 1902, insurrections in the Philippine Archipelago lasted for another decade, and hundreds of thousands of Filipinos died. It is impossible not to be reminded of so many subsequent American wars in Senator George Frisbie Hoar’s rebuke of then-President Theodore Roosevelt: “Your practical statesmanship has succeeded in converting a people who three years ago were ready to kiss the hem of the garment of the American and to welcome him as liberator . . . into sullen and irreconcilable enemies, possessed of a hatred which centuries cannot eradicate.”

Lynn Novick is an Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker and the co-director with Ken Burns of The Vietnam War, which will air on PBS in September.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com