When it comes to the White House, private conversations can easily become part of the public interest — but, President Trump appeared to suggest in a tweet on Friday, they might not all be precisely private.

Seeming to take issue with a report that at a private dinner he had asked former FBI Director James Comey to swear his loyalty, the President tweeted that Comey “better hope that there are no ‘tapes’ of our conversations.”

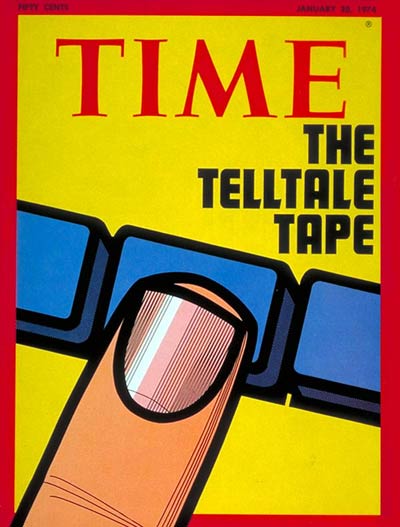

The idea that there might be tapes of a presidential conversation that were made without Comey’s knowledge quickly drew comparisons to the most famous tapes in White House history: the Nixon tapes. But the history of those tapes shows that, while Trump would certainly not be the first U.S. President to think there’d be value in keeping such a record of his conversations, there’s a very good reason why chief executives are generally thought to have stopped making secret recordings.

In the early 1970s, as the investigation deepened into whether Nixon knew about a 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee office at the Watergate, Washington observers began to suspect that there was some secret record of Oval Office happenings. White House counsel John W. Dean III testified that around mid-1972 he began to suspect that the President might be getting ready to frame him, and he began viewing their many meetings with a more suspicious eye.

In April of 1973, he requested a meeting with the President at which, as TIME later reported, “the thrust of the President’s questions led Dean to think the conversation was being taped,” as Nixon loudly proclaimed that he had only been joking about some of the matters they had discussed previously, only to then whisper other parts of the conversation.

But Dean’s hunch was only a hunch until July of 1973, when it came to light that the President had been taping talks and phone calls since 1971, as TIME reported:

By all accounts, the sudden and dramatic injection of the controversy over the Nixon tapes came about almost accidentally. As the Watergate committee’s chief counsel, Sam Dash, explained it, his staff was working methodically on a “proximity investigation” — checking out everyone close to the key figures in the affair. Thus a routine private staff questioning of Alexander P. Butterfield, a former aide to Haldeman and now administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration, was scheduled for Friday, July 13—and the staff, as one member put it, “just lucked out.”

The meeting was considered of such little importance that a junior staff Republican counsel, Donald Sanders, was interviewing Butterfield about White House record-keeping procedures. No Senator or top counsel was present.

Nothing of interest had been learned when, at the very end, Sanders tossed out a throwaway question. Noting that Dean had testified that on one occasion he thought the President was taping a conversation with him, Sanders asked whether “conversations in the President’s office are recorded.”

“Oh God,” replied Butterfield, “I was hoping you wouldn’t ask that.” He put his hand to his head and seemed shaken. He said that he was worried about violating national security and Executive privilege, but could not evade the question. Then he revealed that Nixon had ordered the Secret Service to install recording devices that would pick up any conversations in his Oval Office and his working quarters in the Executive Office Building.

The tapes quickly moved to the center of the Watergate investigation (especially when it was discovered that some portions of the tapes had been erased). Some believed they would exonerate the President, others believed they would prove his involvement and —perhaps most importantly—they eliminated the possibility that the whole scandal would fade out in a blur of he-said-he-said. From that point on, it was clear that there would have to be some kind of resolution. And the more Nixon fought to keep the tapes and transcripts secret, the more that fact was clear. The impeachment soon began, and in 1974 he resigned.

Why had Nixon made the tapes in the first place? Butterfield asserted that the President was simply preserving his actions for the historical record, though others close to Nixon differed on the reasoning: paranoid about his bad relationship with the press, they said, Nixon wanted to be able to prove what he had and had not said. Neither of those explanations was particularly scandalous, but the fact that Nixon had ordered those recordings made—in fact, the microphones went on whenever Nixon so much as entered one of the rooms in which they were placed—without informing others present in the room clearly left him, as the magazine explained at the time, “in a position to manipulate and distort the historical record with self-serving or misleading statements.”

Read more: You Can Compare President Trump to Richard Nixon, But Times Have Changed

But, some Nixon supporters argued, he wasn’t the first to have that idea. In fact, it turned out that for nearly as long as the technology had existed, Presidents had been taping their talks. The revelations about the Nixon tapes raised interest in that history, leading presidential libraries to investigate their holdings.

President Franklin Roosevelt had taped some conversations for a period in 1940, after becoming angry about being misquoted. Though the recording technology was still new, he managed to do so with the help of the president of RCA, who gave FDR “an experimental device similar to machines used in making sound films,” TIME later explained. Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson all followed his lead to varying degrees, later reports revealed, taping some Oval Office conversations and not always with the knowledge of the person to whom they were speaking.

In fact, Henry Kissinger—who had been warned by Nixon to “be careful” about what he said in the Oval Office—would later say that Nixon got the idea to tape his own conversations after he found President Johnson’s old system.

In the wake of the Nixon tapes, however, the perception of Oval Office taping changed dramatically. President Ronald Reagan’s White House, for example, announced publicly that the only presidential conversations being recorded were those with the press, and that such taping was done with the full knowledge of all involved. As presidential historian Michael Beschloss tweeted on Friday, “Presidents are supposed to have stopped routinely taping visitors without their knowledge when Nixon’s taping system was revealed in 1973.”

And yet, it’s clear, despite all the trouble that the tapes caused for Nixon, the lure of the tape endures.

One solution proposed by TIME in 1982: State once and for all that any meetings in the Oval Office and Cabinet Room will be taped, and hit record with no sense of guilt.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com