In many sports, the professional athletes who broke through the boundaries placed around them for being African-American — like Jackie Robinson or Jesse Owens — have remained famous figures of American history decades after their physical feats first made headlines. But when it comes to horse racing, the story has been somewhat reversed. The jockeys who will ride in America’s premiere races, like this Saturday’s Kentucky Derby, are largely white or Hispanic, and many of them hail from overseas; an African-American jockey has not won that race for more than a century. But the sport used to be dominated by African-American jockeys whose legacy is often forgotten.

Perhaps the reason is that their early history with the sport was not the kind of thing that racing fans would prefer to remember. Enslaved men, who worked on the farms of wealthy white men, were the ones who knew the horses best, so they were the original trainers and jockeys. And, though slavery had been abolished by the time the Derby was first run, free African-Americans continued to hold many of the working-class jobs that were necessary to make a stable run. Thirteen of the 15 jockeys in the inaugural Derby in 1875 were African-American, and the African-American Oliver Lewis won the race riding Aristides. African-Americans won 15 of the first 28 runnings of the Kentucky Derby.

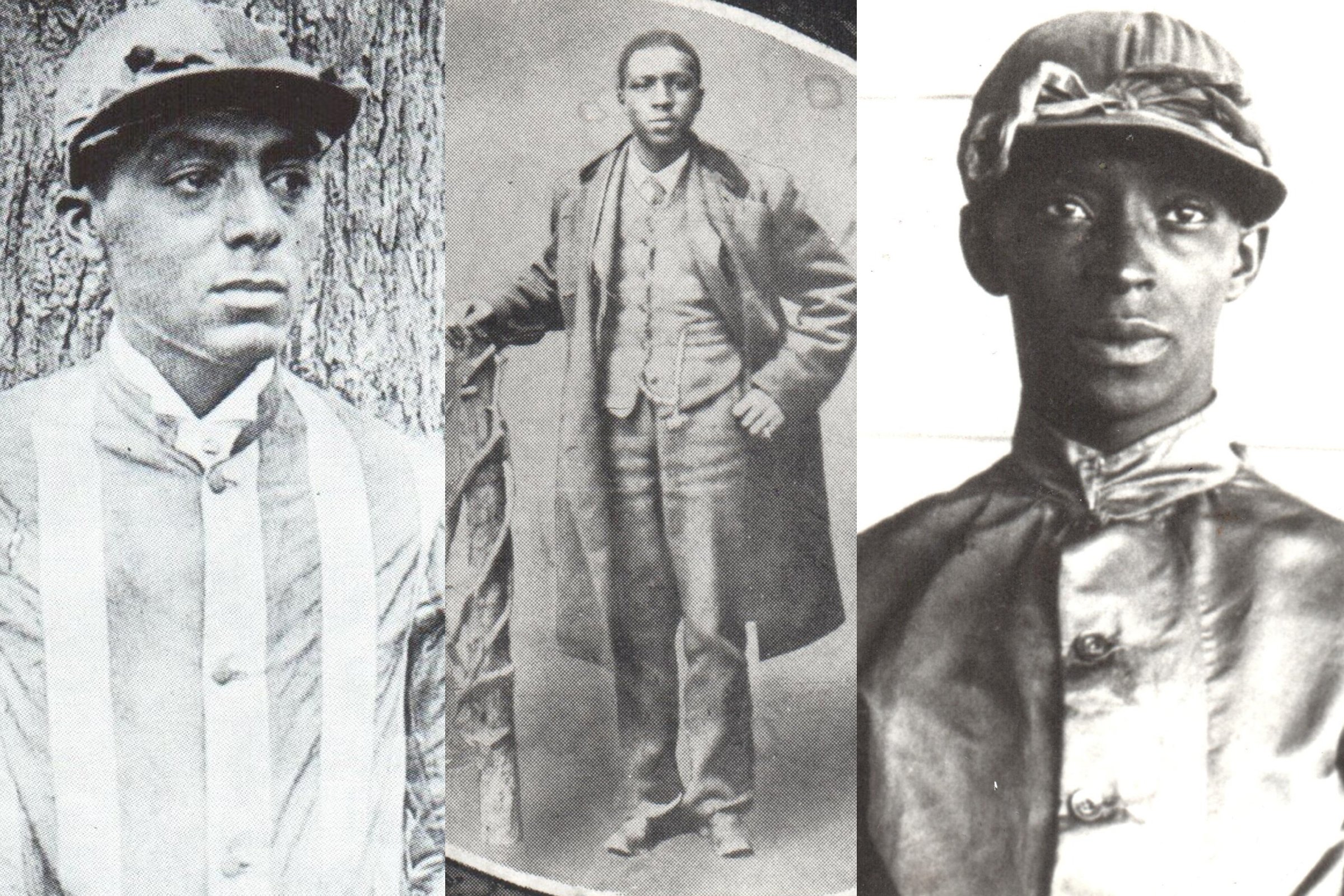

For example, Isaac Burns Murphy, who was inducted into the inaugural class of racing’s Hall of Fame in 1955, is recognized as one of the greatest jockeys ever. He was the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby three times (1884, 1890 and 1891). Born and raised in Lexington, Ky., his mother apprenticed him off to an owner of horses at age 14 because that was seen as the only path to a better life he had. Like many who have been attracted to racing for the thrill and the opportunity, he believed that the right training could earn him a good life as a jockey.

It worked. He mastered the art of pacing, and became so graceful that one newspaper called him an “elegant specimen of manhood.” He managed to make between $15,000 and $20,000 a year (close to a million dollars today), and lived a comfortable upper-middle-class life in a home he bought in his native Lexington, Ky.

Eventually, horse racing became more lucrative not only for the people owning and riding the horses, but for the spectators, too. Races became shorter, so there were more of them, meaning the number of betting pools increased. A system for betting on multiple horses was developed, so there were more exciting opportunities for spectators to make money.

As jockeys who weren’t black saw African-American jockeys making a good living off of horse-racing, Murphy was an example of someone who became “a victim of his own success,” says Pellom McDaniels III, author of The Prince of Jockeys: The Life of Isaac Burns Murphy and the Curator of African American Collections in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University. In the 1890 season, Murphy was accused of being an alcoholic and drunk on the back of a horse. McDaniels says that, in his research, he discovered that Murphy was actually drugged.

Many black jockeys were sabotaged, to the point where, by the early 20th century, they were becoming more of a rarity in the sport. Jimmy Winkfield was the last African-American jockey to win the Kentucky Derby, in 1902, and he ended up going to Europe and making a name for himself in Russia, France and Germany.

Nowadays, McDaniels says, there’s another factor in play in determining who rides at the races: jockeys are usually people who have grown up in rural environments, so people of Latin-American and Caribbean heritage, who may have been more likely to grow up in the country around horses, have become today’s racetrack regulars.

Correction: The original version of this article misstated Pellom McDaniels’s current position at Emory University. He is the Curator of African American Collections in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, not a professor of African-American Studies.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com