On Wednesday, President Donald Trump signed an executive order directing Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke to reassess the size of national monuments designated under the Antiquities Act of 1906, to determine whether the acreage covered by that designation “conforms” with the “requirements and original objectives of the Act,” while balancing “the protection of landmarks, structures, and objects against the appropriate use of Federal lands and the effects on surrounding lands and communities.”

The task of making that determination, however, may a tricky one.

It sounds like Zinke’s report will hinge on a “nebulous figure,” which is a determination of “the least amount of acres needed to accomplish the conservation purposes,” says David Harmon, who co-edited The Antiquities Act: A Century of American Archaeology, Historic Preservation, and Nature Conservation. If the administration decides to reduce the acreage of the monuments as a result of that decision, the sites could be opened up to drilling, mining and logging. Plus, says Harmon, the “original objectives” of the act are often misunderstood.

“Present-day critics who are talking about how its being used in way that it was never intended is bit disingenuous,” argues Harmon. “Congress knew that it was handing it [the Antiquities Act] off to Theodore Roosevelt, who used his bully pulpit, who sent the Navy around the world and dared Congress not to fund it. They knew exactly what kind of guy Theodore Roosevelt was.”

They also knew what else was going on into the world at the time. Roosevelt signed the bill into law on June 8, 1906. In the decades leading up to the signing, Western expansion of the United States had sparked public fascination with the history and art of the American Indians of the Southwest. Organizations of American archaeology and anthropology formed, and their traveling exhibitions displayed their findings on Native American artifacts.

But relatively few of the people involved in that growing field were actually scientists. The rush to find precious prehistoric objects led amateur archaeologists to flock to ancient sites in Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico and start digging. (And it wasn’t just an American phenomenon: Gustav Erik Adolf Nordenskjbld, son of a Swedish geologist and an Arctic explorer, set up camp in what’s now known as Cliff Palace in the Mesa Verde National Park in Montezuma County, Colo., and brought the artifacts excavated by his team back to Stockholm.) As ancient graves were vandalized and wrecked for artifacts, and as the market for forgeries grew, experts worried how far it would go. For example, in 1901, after completing five months of field work in northeastern Arizona, Dr. Walter Hough, an ethnologist for the National Museum (a precursor to the Smithsonian Institution), concluded, “The great hindrance to successful archaeologic work in this region, lies in the fact that there is scarcely an ancient dwelling site or cemetery that has not been vandalized by ‘pottery diggers’ for personal gain.”

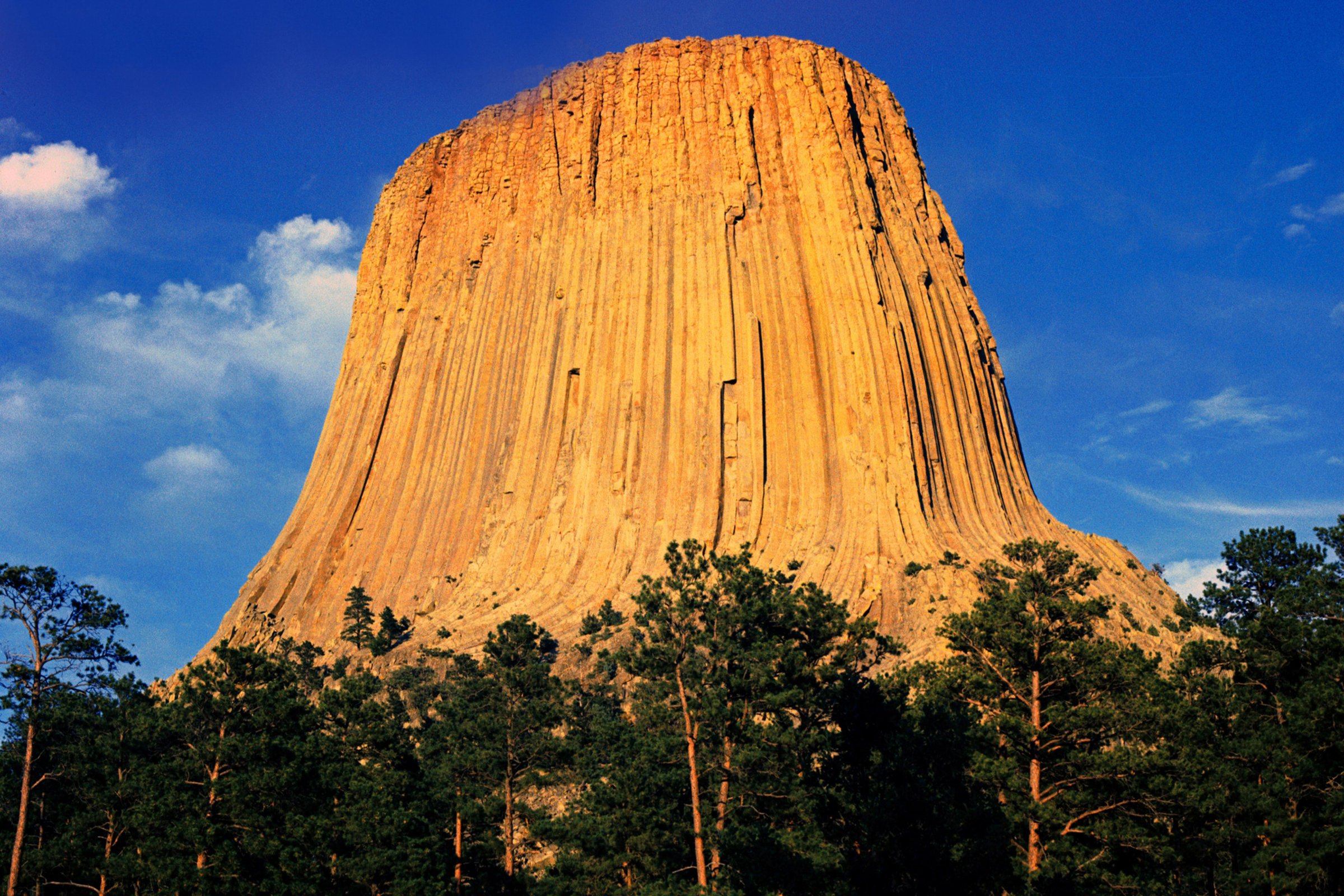

So the Antiquities Act — which gave the President the power to set aside land as “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest” — was a seen as a possible solution, especially in that Progressive era of social activism and political reform. President Theodore Roosevelt started using it immediately, proclaiming Devils Tower in Wyoming (a spiritually significant site in the local Native American community) the first national monument on Sept. 24, 1906.

In the years that followed, he also used that power to protect a wide range of natural wonders. He would go on to use the act to designate 14 more national monuments, including the Grand Canyon and California’s Muir Woods, and he is remembered as the country’s first conservationist president.

And that is exactly what Harmon argues Congress could have expected. (Current Interior Secretary Zinke might have expected it too: he is a self-proclaimed “unapologetic admirer of Teddy Roosevelt,” who went viral for riding a horse to the department’s Washington D.C. headquarters on his first day of work, has said he believes the 26th president “had it right when he placed under federal protection millions of acres of federal lands and set aside much of it as national forests.”) It was no surprise that Roosevelt used the power broadly. In fact, Harmon adds, though members of Congress debated whether to include an acreage limit, like 320 acres, that did not make it into the bill that became law.

Since then, 16 presidents have used the Antiquities Act to designate 157 national monuments.

So far, Harmon says, presidents have usually only rolled back national-monument designations for national monuments that they have personally designated.

But the debate over public use of these lands has changed.

On the one hand, awareness of the importance of environmental protection has grown, and it has become clear how important preservation of areas like national monuments can be. On the other hand, in the early 20th century, when the West wasn’t as populous, this kind of federal authority was widely accepted. Designating monuments helped the local economies and drew visitors to these isolated areas. “But then the population fills in, and states’ rights [advocacy] rears its head, and people become concerned that for every park that’s created, it’s taking private taxable land and making it public place,” says Dwight T. Pitcaithley, former chief historian at the National Park Service. This argument came up recently when Barack Obama used the Antiquities Act more than any other president to set aside more than 3.9 million acres of land for federal protection.

While the original intent of the 1906 law was to stop people from doing whatever they wanted on historic sites, in recent years, people have gotten angry that they can’t do whatever they want on these public lands. This populist sentiment argues that the Antiquities Act’s method of setting aside public lands is actually taking land away from the public, limiting the places they can drive ATVs or graze their livestock, as Pitcaithley explains. Most recently, in 2016, Republican state lawmakers in Utah have fought against Bears Ears‘ national monument designation.

Yet Will Shafroth, CEO of the National Park Foundation and grandson of Colorado U.S. House Rep. John Shafroth, one of the original backers of the Antiquities Act, sums up the importance of the Antiquities Act in a way that may resonate with President Trump: “It’s a tool that Presidents can use to set aside something special for the country for future generations.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com